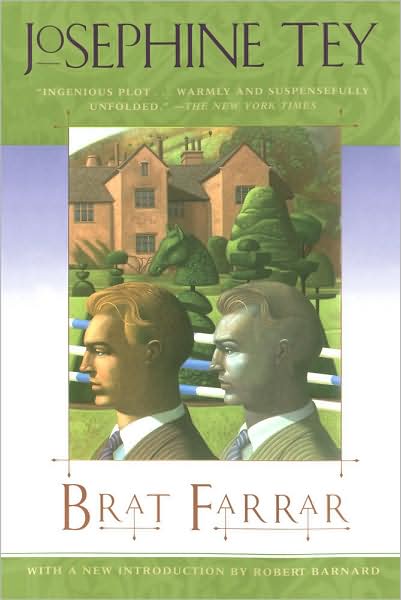

Josephine Tey’s Brat Farrar (1949) is one of my favourite books. It isn’t science fiction or fantasy, it was published as a mystery novel. It also falls into the special genre I call “double identity.”

Brat Farrar is a young man with a pronounced family resemblance to the Ashby family, of Lodings. A brother of about his age supposedly committed suicide—his body was never found—at the age of thirteen. If twenty-one year old Brat were the dead Patrick, he’d inherit the estate and all the money over the head of the smiling confident Simon Ashby. Brat encounters Alec, a rogue who knows the Ashbys well and Alec immediately concocts a plot. Brat is drawn into the affair at first from curiosity and later from a desire to avenge Patrick. This is a murder mystery as well as a double identity story, but the murder Brat is investigating is that of his own double, and he can’t reveal the truth without revealing his own deception.

The wonderful thing about Brar Farrar is the detail. The family at Latchetts is drawn very realistically, down to the details of their table manners and table talk—and this is a large part of the charm of the book. It draws you in to the story of them as people, as a family—the aunt who has been in loco parentis for eight years, the twin eleven year olds who are so different from each other, the sensible Eleanor, the charismatic Simon. Brat himself is fundamentally nice, and Tey shows him going through contortions to accept the deception. This is a double identity book where the family feels real and the possibility of revelation through the minefield keeps you on the edge of your chair.

The way Brat manages the deception, with intensive coaching from Alec Loding, feels realistic—we’re given just enough detail, and the details are very telling. The little horse he “remembers,” and its mock pedigree, “Travesty, by Irish Peasant out of Bog Oak” is just the right kind of thing. And the resemblance, being a general family resemblance and not a mysterious identical one, with the eventual explanation that he is an Ashby cousin, seems plausible. The growing sense that he is Patrick’s partisan and his need to find out the truth of Patrick’s death, is all very well done. The trouble with this kind of story is “usurper comes home and gets away with it and then what?” Tey gives a very satisfying “what,” an actual mystery that resolves well, an impressive climax, and a reasonable resolution.

Brat Farrar is set in the time it was written, though actually contemplating the world in which it took place gave me a great idea for a series of my own. I don’t know quite when Tey thought she was setting it. We see some technological evidence of 1949, but the atmosphere is that of the thirties. There’s some evidence that WWII happened—a dentist was bombed in the Blitz—but it doesn’t seem to have had the social effect it did in reality. This is a 1949 in which people cheerfully went on holiday in France eight years before and in which a thirteen year old running away seven years before could cross France and get work on a ship there—in 1941 and 1942? Surely not. I managed to read this book umpteen times without noticing this, but once I did I couldn’t get it out of my mind. Anybody who would like more books set in my Small Change universe can read this as one. It was partly to recreate the atmosphere of reading the domestic detail and comfortable middle-class English horsiness of Brat Farrar with the thought of Hitler safe at the Channel coast and nobody caring that I wrote them. Of course, this makes re-reading Brat Farrar odd for me now. But even so it absolutely sucked me in for the millionth time and I read it at one gulp.

Jo Walton is a science fiction and fantasy writer. She’s published eight novels, most recently Half a Crown and Lifelode, and two poetry collections. She reads a lot, and blogs about it here regularly. She comes from Wales but lives in Montreal where the food and books are more varied.

I had wondered the same thing when I read it. Is there any way for her to have meant to have set it a few years before, enough to leapfrog the war? If it was published in 1949, but set in, say, 1946 or 7, it seems more plausible.

That introduces a new problem, with two twenty-one-year-old boys who would have been eighteen during the war, and no explanation of why they weren’t in the army, of course. So maybe it just can’t be made to work well.

“Brat Farrar” is one of my all-time favorite mystery novels. However until reading this I never noticed how the era it was set in didn’t make too much sense especially LizardBreath’s comment on why the boys weren’t drafted into the war effort nor any other mention of the effect of the war on the family.

I too loved the line Travesty, by Irish Peasant out of Bog Oak though it took me a time or two to see just how clever it was.

Tey’s “Daughter of Time” is often referred to and “The Franchise Affair” has been made into a couple of movies but I think “Brat Farrar” is her most unforgettable. It was also made into a miniseries but unfortunately the show didn’t capture what I loved about the novel.

WWII was so disruptive of everything that the events of the story couldn’t have happened as described if it had happened, not just the France thing, though that’s the most obvious, but the boys as you say, and the general timeless calm of the countryside, and even little things like Nancy Ledingham’s coming out couldn’t have happened between 1939 and 1945 — and yet the dentist was bombed in the Blitz, so it isn’t still the thirties.

(I’ve thought about this a lot, as I said.)

Maybe the dentist was a mistake. Remember Brat’s mother was said to have been killed in ”the war”, which would have had to be WWI. The feel of the whole book was pre-1940s and WWII.

I wonder if there’s any evidence that she wrote it long before it was published, and just updated it with the dentist reference in the late forties.

LizardBreath: There’s strong evidence against that — I have read all of Tey in publication order, and doing that you can see the way she improved steadily at her craft as she went on.

I think it was like the way you sometimes get older writers writing about young people and imagining their lives in terms of the decade when the older person was young — people writing about raves as if they’re just discos with different music, or writing about drugs in highschool as if it was still the sixties. She wanted to write a pastoral novel and she set it “now” without really thinking about whether it made sense. I mean mainstream writing, setting things in the real world and real time, is very odd when you think about it, because the characters have to be shaped by history, and you can’t shape the world to the way you want the characters to be. Weird.

I’m not complaining — as I said, I’ve written a trilogy explicitly set in the 1949 Tey imagined she was living in.

It reads like something partly written in the 1930s, maybe a complete version, and lightly edited to throw in a reference to the war.

It’s just possible to fit the story around the war, with Patrick’s death before the war and the 21st Birthday in 1946, but there’s so much missing. Not even a mention of ID Cards and Ration Books.

Though there is a way of fitting the story into the War. Brat Farrar joins the US Army, and that gets him to England in about 1943. But can he claim to be Patrick Ashby without looking, to his fellow soldiers preparing to invade France, to be a coward? And what is Simon doing? (Possibly wangling a nice, safe, job in an Army headquarters somewhere.)

Heck, there’s that Alan Ladd movie, The Red Beret, in which he plays an American who enlists in the British Army. But putting the story into an Army camp would throw away all the interesting elements of the original.

When I read the book, I almost skim over the isolated references to the war. It’s a 1930s mystery novel.

Dave: Every month of Brat’s life in France, Mexico and the US is accounted for. He did not join the army. She could have done that if she wanted to.

And she definitely didn’t write it earlier, the textual evidence is against it.

Brat Farrar is my favorite Tey. Partly, it’s the horses- I still love me a pony story- but mostly it’s Brat’s character. Plus of course, Ruth and Jane, the twins.

The boarding school, where no one has to learn, is what threw me. I always thought of that type of education as a more 1960’s phenomenon.

I don’t think that I want to imagine Brat and Co as inhabiting the Small Change universe- they would end up being discovered as secret Jews. and it would all be over.

Pam: No, it’s much worse than that. They live there, just like that, nothing stops them, they just keep on living like that while Jews and other people… don’t.

They had schools like that in the thirties. Summerhill is the famous one.

There are similar though less marked peculiarities in the setting of The Franchise Affair; here, again, the Blitz has happened (conveniently, to orphan an evacuee) approximately ten or a dozen years earlier but there is no mention of rationing and neither the forty year old solicitor or his 27 year old cousin appear to have served in the War or done National Service.

With regard to Brat Farrar, Brat actually has to be slightly older than Patrick/Simon – he runs away after he has left the grammar school and when he’s been working in an office for some time; arguably at the age of 15 or so. This doesn’t make the War bit any less baffling; it simply means there’s an even longer spread of time to account for.

In The Silver Chair CS Lewis creates a very similar boarding school in Experiment House (he was in regular correspondence with someone who taught at Dartington Hall, which may have served as a model) and Monica Dickens references one in Flowers on the Grass, set in the 1950s.

I remember noticing the “when is this happening?” issue the first time I read the book, but I just let it go, like the Long Year in Patrick O’Brian.

Maybe it is set in the same AU as Cold Comfort Farm?

It gets harder to understand when you think it wasn’t just the author. After all, this book wasn’t self-published, and everyone in a position to get the text changed had to have either had the same blind spot, or not cared.

I was amazed to see, when I recently watched the live-action film of 101 Dalmations, that there were raccoons and a skunk in plot-significant roles. Half the actors were British, and half the crew probably were too. Didn’t anyone say anything?

And the school is absolutely period-correct. “Experimental” and “progressive” schools date back to the 1890s in England (Bedales) and to about the same era in the US and Canada; they had a tremendous resurgence right after World War I, with Summerhill being perhaps the best known of the many English schools on this model founded in the 1920s.

legionseagle@11,

You’re right- and Eustace’s parents were just the type to send kids to a school like Clare.

I never noticed that! I have read it umpteen times and never paid the least bit of attention to the dates, just suspended belief and fell into the story, as I do with Dodie Smith’s novels.

The same is true for The Daughter of Time. I once read a mystery novel which spent a fair amount of its time debunking Tey’s history and painting Richard III as the blackest sort of villain. Unfortunately, the novel was indifferently-written, and I no longer remember its name or author. What the author failed to take into account is that we read The Daughter of Time for Alan Grant and the people around him, not really for Richard III.

And she definitely didn’t write it earlier, the textual evidence is against it.

While I think you’re almost surely right, I think “definitely” is too strong; she could have polished it up to any extent later, after all. Does anyone know whether Tey’s papers are in an archive anywhere? There were some left; The Singing Sands was discovered among her papers after her death.

I loved Brat Farrar! I loved all Tey’s books but this one really has a lovely feel of being set in a real place with a real family. I had never noticed the time discrepancy. The concept of a “belonging place” was a powerful idea; I could identify with Brat for wanting one. I read the book decades ago, but I still remember the little touches, like Patrick’s mother had kept all her family photographs loose in a tin instead of in albums, and it had been lost with her so there were few pictures of Patrick. I liked the resolution, too.

I have loved this book for so long; it’s a treat and a confusion to conflate it with the Small Change series, which I love differently and more recently.

I love this book – now I’m due for a reread!

One of the bad things about the miniseries is that they made the house/estate (and thus the family) far too posh. The family had been there ‘forever’ but the house originated as a farmhouse, much added onto.

Chazzbee: I think the precise level of class in the book is one it would be very easy to misunderstand. Tey is really really interested in class, much more so than most writers even of her own time.

Incidentally, another “what world is this” moment in this book is when talking about the plausibility of doubles, Brat thinks that Hitler had several, and doesn’t think of Hitler with any particular animosity, or even particularly in the past tense.

I always loved Brat Farrar, too. Another author who evokes that sense of place and class is Antonia Forest, especially in the books set at the Marlows’ home (instead of at the girls’ boarding school, which is nothing like the one in Brat Farrar!). Interestingly, in spite of the main characters of the stories being twins, I don’t think Forest ever really uses the double identity trope, at least not more than briefly. Forest also does interesting things with time; in spite of the books taking about two and a half years of the characters’ lives, they are set pretty much at the time of writing, spread over four decades–as Forest says, “in that mythical time we call ‘since the war'” (or words to that effect).

One of my favorite bits is the hotel before the horse show- the family (and others) have attended so many times that their rooms are permanently ‘theirs.’

Good grief–I’ve read this book so many times and never thought about era! I blame the BBC adaptation, which is set, much more logically except for the fact that Tey was long dead by then, in the 1980s. It’s a wonderful adaptation, though; very true to the book in all respects that matter.

I’ve never been much of a mystery reader, but I’ve been on a kick recently since reading your Small Change series. It led me first to Dorothy Sayers, and then to Brat Farrar just this week. I absolutely loved this book. It had something to do with the first chapter, and the way I was dropped into a family that felt utterly real, every member distinct and true. Brat, too, was a fine character, with complex and compelling motivations. I love the shades of gray within this particular case of double identity.

Also, I’m a horse person, and often get irritated with books that don’t get horses right; Tey absolutely got it right.

I was so taken with the family and the setting and the horses and the mystery that I have to admit I didn’t notice the missing war.

great book, great review of a great book… from a great writer! i was wondering is anyone had noticed the possibility of BRAT being a somewhat of an inspiration to RIPLEY? very different in major ways – not the least fo which is that tom ripley is a lovable sociopath and brat actually has a herat and conscience… but i bet that miss highsmith knew and loved tey’s books, and this one in particular – she just inverted it in her inimitable way. all along i was was sure one of the twins had killed the other, but i was secretly hoping patrick had killed simon and then had *become* simon… great fun!

Another reference to the war comes at the end of the book when Bee is telling Brat that they have found out that his mother was a nurse. “She was killed during the war, taking patients out of a ward to safety in a shelter.” I received the book as a school prize in 1968 and read it during the school holidays. I have read it several times since, each time picking up more enjoyable details about the very believable characters and their world and the truly gripping plot. One of the best!

Thank you for a wonderful description of one of my favorite books ~ i read it first in the mid-1960s, and have re-read it at least once a decade since! I played around once with when all the Ashbys had to have been born so that the timing worked out around the second world war, the parents’ death, and Brat’s stowing away to America, and decided as a result that Simon and Brat were turning 21 in the mid-1950s, even though the story was published in 1949/50. Yet I agree with those who say the feeling and tone of Latchetts is that of a pre-war English countryside. What an interesting conundrum to be left with, from a fine writer!

I have just finished rereading “Brat Farrar”, my favourite Josephine Tey, and looked it up to see what others had to say. I did enjoy reading this review and the various comments different people have made.

On the matter of the time, I have always read it as being set in the mid 1950s, and internally that almost works (though I realise it was some years after publication date). For example, the gap between Eleanor and the younger twins could well have been caused by their father being involved in the War, so they were born about 1946, therefore Patrick and Simon were born about 1935 and Eleanor in 1936. Brat was probably a year older, which would also fit with his mother being through her training and being killed while working during the War. About the only thing that doesn’t fit that is that if the dentist was killed during the War (even at the very end of it) the children would have been to another one after that.

I’m happy to suspend my disbelief and just enjoy the characters and the story. And I liked having a character with whom I share my name!

Thank you for this! A great review of one of my favourite books. In fact,I think this is so wonderful that I’m going to cite it in my dissertation (which is all about Josephine Tey and her obsession with the past).

You’re one up on any ‘professional’ Tey critic I can find – the only person who’s taken the time to properly notice how impossible all those France details are. Kudos!

Well, let’s see: Simon was 21 in 1949, so born in 1928; he would have been 11 at the outbreak of the War, and six years later, in 1945, seventeen. If Eleanor was a year or two younger, she would have come out in about 1947 or 48, and it could have been a sort of tea/dance. Remember, too, that farms are self-sufficient (or try to be), so ration coupons were not as necessary. And the well-off, I imagine, could still get clothes, since tailors were still in business: Unlike today, they were seen as long-term purchases, so the cost stretched out over several years. So I’m not sure the timing requires a great deal of adjustment, really.

Price: Except Brat ran away when he was 13 and went to France — in 1941. Not really possible!

A lovely review. I finished the book this morning and love it – for the detail, for the weaving together of all the story lines, everything.

Didn’t realise you were a Montreal author! :-)

I’m surprised neither your review nor Wikipedia mention the interesting fact that Tey stipulated that all author’s profits from this book are to be dedicated to the National Trust.

(I’m blogging at http://www.thegirdleofmelian.blogspot.com)

There was a Blitz in WWI as well. The zeppelin bombings.

I just listed to the wonderful audiobook. I don’t remember the Blitz comment, but I do remember that an older man in the story had sons who died in one war and grandsons in another. The wars could be the Boer War at the turn of the century and the 1914-18 war.

I think the setting is the late-twenties. If the boys were born in 1907 or ’08, they’d have been too young for WWI.

I had always assumed that the dentist’s office blew up because of the gas they used to use on patients. Tey never says that the dentist was killed in the Blitz. If Brat’s mother was killed during the war, when he was a baby, it would have been over by the time the Ashby children were going to the dentist

I just finished my quasi-annual reread of this book, and for the first time in more than 30 years (!) found myself completely shocked by the ending, in a way that had never struck me before. [SPOILERS] Did the Ashby family really consign Patrick’s remains to anonymous disposal, while burying the murderer Simon with all respect and honor, just to avoid scandal?! And then ship the girls off to boarding school as if nothing had happened? I always found the romance between Eleanor and Brat a little much, but now I’m wondering why Brat would want to attach himself to these monsters?

I’ve also fussed with the dates every time I reread it. Ditto for The Franchise Affair: a war is mentioned in connection with the longtime secretary at the law firm, but it’s impossible to make it fit with either war.

I have wondered if this is related to Tey’s known isolationism/pacifism wrt to WWII. (Richard of Bordeaux, from 1933, is an anti-war play.)

It may be that she simply refused at some level to acknowledge the existence of WWII, even when she refers to it obliquely.

Reading this now, during what is unquestionably the largest global event and tragedy to take place since WWII, the lack of clarity in date details make so much more sense to me. We can see it even now in the midst of the pandemic – so much media being created simply ignores the pandemic, because the scope and horror of it is so unimaginable. It’s not a surprise to me that so many mystery and genre novels written during the 30s and 40s all but ignored the war. I understand that now in a way that would have felt inexplicable before.

Rereading Brat Farrar, I came on this:

“Was that the Toselli child you had out with you?” she was saying to Eleanor. “That object I met with you this afternoon?”

“That was Tony,” Eleanor said.

“How be brought back the days of my youth!”

“Tony did? How?”

You won’t remember it, but there used to be things called cavalry regiments. And every regiment had a trick-riding team. And every trick-riding team had a ‘comedy’ member. And every comedy member of a trick-riding team looked just like Tony.

My maternal grandparents grew up in what was then called Royal Hungary. Nowadays it’s called Slovakia. My grandfather was a Hussar. More than that, he rode in his regiment’s trick-riding school. One of his tricks was to ride three horses, side by side. He stood on his head on the center horse, with a hand on each flanking horse. He used to demonstrate it to my mother, using three kitchen chairs.

If Brat took his day trip to Dieppe early in 1939 before the outbreak of war that would place the main events of the novel no later than 1947. Brat’s leg injury would have made him ineligible for military service in the US. Simon would have been called up in 1944, but by the time he had completed officer training the war would have been all but over so he may never have seen active service. Where would Westover be I wonder? It is south of Bures (which is a real place), so probably Colchester. Clare is supposed to lie east of Westover where, in the real world, there is a group of villages called…the Teys! I think the author liked to hide little clues like this. For instance, Alec Loder shares his surname with a person who was involved in the Tichborne case on which the novel was based.

Simon would have been called up in 1944, but by the time he had completed officer training the war would have been all but over so he may never have seen active service.

Or Simon could have deferred or avoided his callup due to being a student (in which case they waited until you graduated); being in a reserved occupation such as farming; or being medically unfit. The callup wasn’t universal at age 18.

I also wonder if it isn’t so much Tey that is ignoring the impact of the War, as we who are over-emphasising it. Pre-war attitudes weren’t universally and wholly swept away from Britain on 3 September 1939. Most people in any given decade are living in ways we generally associate with previous decades; most people in most of the 1960s weren’t living in THE SIXTIES, but in a sort of extended 1950s.

I remember coming across a few old wartime copies of Punch and being startled by how few references to the war there were. A couple of advertisers said that their cigarettes or cocoa were as used by the troops. There was one cartoon about rationing. It wasn’t a universal perpetual obsession; people still cultivated their gardens.

I agree that Simon could very well have deferred or avoided his callup. The character strikes me as someone who would know how to wriggle out of something like this. I also take your point that we may tend to over-emphasise the effect of the war on a rural community. I recently watched a TV adaptation of The Franchise Affair which went to great lengths to establish a post-war setting (long ration queues, uniforms everywhere). It just looked a bit overdone to me.

I, too, loved this book Didn’t notice the dates, but wondered how Brat obtained a passport from USA to UK. He had no birth certificate or other ID. The orphanage that brought him up sounds like George Muller’s.

Without thinking too closely about it, the setting for me felt like taking place between WWI and WWII, perhaps in the early 1930s. It’s hard to see this being set as just after WWII when Britain still had food rationing and was reeling what they’d just been through. Even Brat’s real mother who so wanted to be a nurse and went off to be one during the war bears this out – if she gave birth to Brat in 1910 or 1911, then died during WWI (which is referred to in the book as ”the war”) it would put him at 1932-33 when he gets to Latchetts.