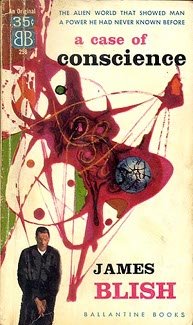

James Blish’s A Case of Conscience is a very peculiar book indeed. I first read it years ago as part of the After Such Knowledge series. The other books in the series are explicitly fantasy or horror, this is science fiction set in a universe in which Christian theology as Blish imagines it is explicitly true. It’s written in two distinct halves. In the first half, a four man expedition to the planet Lithia, discovering it to be inhabited by aliens, discusses what recommendations they will make to their superiors. In the second half, a Lithian grows up on a decadent and dystopic Earth and causes chaos there.

It’s like shooting fish in a barrel to point out all the things that are wrong with this book, from errors of theology and science to question begging and jumping to conclusions. But it’s also very good. It’s written in a quiet but compelling style that’s thoroughly absorbing. It’s easy to swallow the absurdities as I go along, it’s only on reflection that they leap out. It has genuinely alien aliens, and we see one of them grow up from inside. It’s very unusual and quite unforgettable. It won the 1959 Hugo, and it’s good to see it going to a philosophic adventure story like this.

Four men were sent to Lithia, the Jesuit Father Ramon, a biologist, Cleaver, a physicist, Agronski, a geologist, and Michaelis, a chemist. Almost the whole first half of the book is taken up with them squabbling over what is to become of Lithia. Cleaver wants to make it into a sealed atomic research planet, Michaelis wants to open it up to trade and contact, Agronski will go along with whoever makes a good argument and Father Ramon at first wants alien contact and then wants the entire planet sealed off as it’s a temptation created by Satan. The weirdest thing about this is that Lithia is the first planet inhabited by aliens that humanity has found. This is the first alien biology, the first alien language, the first alien civilization. It’s amazing that humanity would leave a decision about how to deal with that to one four man team, or that anybody, no matter how obsessed a physicist, could even think that the potential for making bombs was more valuable than the actual living aliens.

The second half of the book is back on Earth—a horrible overpopulated and decadent Earth in which everybody is living underground for fear of a nuclear attack that never happened, and frantically having decadent parties or watching TV. This could be considered satire, except that it’s too odd. Egtverchi, the Lithian who grows up among humans, does not instinctively follow the calm reasonable and utterly Christian-avant-le-dieu morality of the Lithians, but instead joins in the decadence and tries his best to destroy Earth in rioting once he has his own talk show. (No, really.) The very best part of the book describes his coming to consciousness from his own point of view. There’s not much science fiction about becoming conscious and self aware—only this chapter and Egan’s “Orphanogenesis,” yet it’s a very interesting idea.

The book ends with Father Ramon exorcising the planet Lithia by FTL radio as the planet is simultaneously destroyed in a nuclear explosion as part of one of Cleaver’s experiments.

Father Ramon seems to me to jump to conclusions about the demonic nature of Lithia, and the Pope is no less hasty in his conclusions. Their reasons are very odd. Firstly, the Lithian process of growing up recapitulates evolution—they are born as fish, come out of the water and evolve through all the intervening stages up to sentience. The idea is that because this utterly proves evolution, people won’t believe in creation. This doesn’t seem like a Catholic position to me.

Secondly, once they’re sentient they are reasoning and reasonable and without any religious instruction they naturally seem to follow the Christian code as laid down by the Catholic Church. Father Ramon believes the devil made them and nobody could resist the temptation of seeing them and ceasing to believe in God — despite the fact that creation by the devil is the Manichean heresy, and he knows it is. The Pope believes they’re a demonic illusion that can be exorcised, and the text seems to go along with that.

I think what Blish was trying to do here was to come up with something that a Jesuit couldn’t explain away. I decided to try this on a real Jesuit, my friend Brother Guy Consolmagno, SJ, an astronomer and keeper of the Pope’s meteorites. (He also has the world’s coolest rosary.) I asked him first about evolution and then about the other stuff.

Well, to start with, that’s not and has never been any kind of traditional Catholic teaching about evolution. Certainly around the time of Pius X (say 1905) when the right wing of the Church was in the ascendency (following Leo XIII who was something of a liberal) there were those in the hierarchy who were very suspicious of evolution, but even then, there was never any official word against it.

As an example of what an educated layperson at that time thought about evolution, may I quote G. K. Chesterton, who in Orthodoxy (published in 1908) wrote: ’If evolution simply means that a positive thing called an ape turned very slowly into a positive thing called a man, then it is stingless for the most orthodox; for a personal God might just as well do things slowly as quickly, especially if, like the Christian God, he were outside time. But if it means anything more, it means that there is no such thing as an ape to change, and no such thing as a man for him to change into. It means that there is no such thing as a thing. At best, there is only one thing, and that is a flux of everything and anything. This is an attack not upon the faith, but upon the mind; you cannot think if there are no things to think about. You cannot think if you are not separate from the subject of thought. Descartes said, “I think; therefore I am.” The philosophic evolutionist reverses and negatives the epigram. He says, “I am not; therefore I cannot think.” ’ (from Ch 3, The Suicide of Thought)

In other words, it’s not the science that was considered wrong, but the philosophical implications that some people read into evolution. (In the case Chesterton was referring to, he was attacking the strict materialism that saw no differentiation between a man, an ape, and a pile of carbon and oxygen and other various atoms.)

Granted, this was written about 15 years before Chesterton formally entered the Church, but you can find similar statements in his later books (I don’t have them in electronic form so I can’t search quickly). And no one would call Chesterton a wooly liberal by any means!

A classic, specific endorsement of evolution in Catholic teaching came in 1950 with Pius XII’s encyclical Humani Generis, which basically makes the same point as Chesterton about accepting the possibility of the physical process of evolution while being wary of possible philosophical implications that could be drawn from it.

So, point one: even by the time that Blish wrote his book, this description of Catholic teaching of evolution was not only inaccurate, it was specifically contradicted by a papal encyclical.

Point two: as you point out, the attitude described is Manichean, which is not only not Catholic but even moreso not Jesuit. The whole nature of Jesuit spirituality, the way that we pray, how we think about the world, is one that specifically embraces the physical universe. “Find God in all things” is the sound-bite mantra. That’s why we’re scientists. If the world, or any part of it, is a creation of the devil (that idea itself is contrary to traditional Christianity since only God can create, and the devil is merely a shorthand way of referring to the absence of good, not a positive entity in itself) then why would you want to wallow around in it, studying it as a physical scientist?

Likewise it was the Jesuits who were the strongest (and still are) for “inculturation” and accepting alien cultures, be they Chinese or techies, for who they are, and adapting religious practices into a form and a language that can be accepted. Our best records of non-European cultures comes from Jesuit missionaries who were the strongest at protecting those cultures from the bad effects of western influence… often at great expense to the Jesuits themselves (for examples, look up the Reductions of Paraguay, or the Chinese Rites controversy).

But I guess I am confused here about what Blish is trying to do. Is the main character becoming something of a Jansenist? It was the Jesuits who most forcefully attacked Jansenism (which is, after all, where the phrase “Case of Conscience” first comes from), and which can be taken as a kind extreme version of Manicheism. (And they accused the Dominicans of being too friendly to that point of view. Maybe the main character should have been a Dominican?)

Point three: every scientist is used to holding two or three (or six) contradictory thoughts in their heads at the same time. That’s what science is all about—trying to make sense of stuff that at first glance doesn’t make sense, that seems to contradict what you thought you understood, and thus come to a better understanding. So any scientist (not just a Jesuit) would be excited by encountering contradictions, and would be horrified at trying to destroy the evidence that doesn’t fit.

Point four: what does it mean to have a “soul”? The classic definition is “intellect and free will”—in other words, self awareness and the awareness of others; and the freedom to make choices based on that awareness. Freedom immediately demands the possibility of making the wrong choice, and indeed of making a choice you know is morally wrong. So how would you know that a race of creatures that didn’t “sin” was even capable of sinning? If they are utterly incapable of sin, they are not free. Point five, and somewhat more subtle… even official church teachings like encyclicals are not normative rules that demand a lock-step rigid adherence; they’re teachings, not rules, and meant to be applied within a context, or even debated and adapted. For example, there’s a lot of Pius XII’s encyclical which says, in effect, “I don’t know how you could reconcile x, y, or z with church teaching”—but that kind of formulation leaves open the possibility that someone else, coming along later on with more x’s and z’s to deal with, will indeed figure out the way to reconcile them. There’s a big difference between saying “you can’t believe this” and “I don’t see how you can believe this” since the latter keeps the door open. Indeed, it is not the idea of sin that is hard to swallow in Christianity (just read the daily paper if you don’t believe in the existence of evil) but the concept that it can be forgiven, constantly and continually.

As for creatures who have no sin… what’s so hard about accepting the existence of such creatures? Aren’t angels supposed to be exactly that?

So, if Brother Guy had been on Lithia, we’d be in contact with cool aliens and finding out as much as we could about them.

Meanwhile A Case of Conscience remains a readable and thought-provoking book.

Jo Walton is a science fiction and fantasy writer. She’s published two poetry collections and eight novels, most recently Lifelode. She has a ninth novel coming out in January, Among Others, and if you liked this post you will like it. She reads a lot, and blogs about it here regularly. She comes from Wales but lives in Montreal where the food and books are more varied.

Well done on getting the Jesuit POV! I shall have to read it again now with this in mind.

Not sure about “The other books in the series are explicitly fantasy or horror” though. It’s a while since I read Doctor Mirabilis, but I remember it as being a straight historical novel about Roger Bacon; is there something I’ve forgotten that makes it fantasy?

As you know, Carandol, I don’t have a copy of Doctor Mirabilis, because it was always yours and you kept it when we divided our books. I remembered it as being fantasy, but it’s a long time since I read it and I certainly can’t remember why. Maybe it is just a historical novel. It isn’t science fiction anyway.

Anybody else read it?

I feel that the climax of A Case of Conscience depends on a theological argument and not a scientific one, so I find it problematic as a work of science fiction. And I did like the theology of Black Easter/The Day After Judgement more.

Will you be sending Brother Guy a copy of Mary Doria Russell’s The Sparrow/Children of God, which details a Jesuit expedition to Alpha Centauri for first contact? Alas, I must say that the portrait of the main Jesuit character is not terribly uplifting.

And for some further discussion of science with Brother Guy and Father George Coyne, director emeritus of the Vatican Observatory, please see this episode of the public radio series “Speaking of Faith” (now called “Being”), hosted by Krista Tippet:

http://being.publicradio.org/programs/2010/asteroids/kristasjournal.shtml

Eugene: Brother Guy and I are united in disliking The Sparrow — he dislikes its humourlessness and I dislike how implausible the behaviour of the humans is. You needn’t look forward to a Sparrow post from me, I’m never reading it again. The one thing I really can’t forgive in a book is having characters who act stupid for no reason but to make the plot work.

In response to your description of Blish’s plot and arguments, I can only quote Saint Ivins: “Do what?” Whether or not ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny, I can’t imagine any way it could prove it. Nor can I follow how an alien species instinctively behaving according to Christian morality disproves the existence of G-d. I should think it would prove it–or at least prove the existence of the author.

Brother Guy’s take on the situation seems much more sensible than Blish’s. Maybe more book reviews should include consultation with the Vatican!

Jo: Sorry to bring up an unpleasant experience for you and Brother Guy. I did not think the Russell books to be an “idiot plot”, but I may be too forgiving. I did like the portrayal of Sofia Mendes, who survives sexual abuse to become, first, a scientist and later a liberator. But, her heroism does seem to come at the expense of Father Emilio Sandoz’s own suffering.

Science fiction is liberally populated with Jesuits, our favorite order of Catholic priest. Perhaps discussing Arthur Clarke’s “The Star” would be more suitable for you and Brother Guy?

“Doctor Mirabilus” was a straight historical, as I recall – one vision, accepted as such by the logic of the times but never made out to be anything else by any authorial nods or winks.

I believe that the theological problem with Lithian ontogeny was that it strongly suggested that the soul arose through natural processes during the phylogenetic process, without any call of divine intervention. Perhaps Bro. Guy can correct me, but I thought that this was a sticking point for Catholic thought.

Any call for divine intervention. For.

Dammit.

The soul is the substantial form of the body, and must be considered within the metaphysic of matter-and-form. A substance is a matter united with a form. (E.g., A Case of Conscience is a substance: it is the story matter united with the form of a novel.) The soul is not a substance per se.

The Early Moderns bollixed it up when they began to think of the soul as a separate substance from the body and kicked off the “traditional” problems of philosophy and “400 years of philosophical squid ink.” Does anyone worry how a sphere interacts with rubber to make a basketball? Of course not. The sphere just is the form of a basketball. Then why worry about how a soul interacts with the body to form a man?

Consider an analogy: “If triangles were alive, geometric figure would be its body and three-sided would be its soul.”

Now, the Latin term translated as “soul” is anima, which simply means “alive.” The question “Does X have a soul?” reduces to “Is X alive?” The existence of a soul is thus empirically verifiable.

One detail in this case is the particular powers of the soul; and these differ between the inanimate form (not properly a soul) and the animate soul, and between the vegetative, sensitive (animal), and rational souls. Each possesses powers that the lower order does not. Plants live in a very different way than do animals; and humans live in a different way than other animals. But like the layers of an onion, each kind of soul incorporates the lower forms. In particular, in addition to the animal powers of Sensation->Perception (Imagination)->Emotion->Motion, the human soul adds Conception (Intellect)->Volition (Will). That is, the intellect reflects upon the perceptions (that big blue bouncy ball) and forms conceptions (ball, sphere, pi, blue, color, etc.) The will is an appetite for the products of conception, just as the emotions are appetites for the products of perception. (Hence, intellective appetite and sensitive appetites.)

All that long way around the barn to say this: a form cannot be supported by just any matter. The subject matter suitable for a short story cannot support the form of a novel. If water is divided into smaller pieces, it ceases to have the form of wetness; and at some point becomes hydrogen (and oxygen), then protons (etc.) then “quarks”, and so on.

Therefore, some evolution — the term refers to unrolling a scroll in order to read it — is necessary for the physical matter to become complex enough to support a rational soul (form). But the form as such, being immaterial — you can point to things that are spherical, but you cannot point to sphere as such — it is not subject to physical processes. That is, logically, the soul cannot evolve since it is not material.

Given that the above was developed by Dominicans, Franciscans, and Benedictines, I don’t think they’d fare any differently than would a real-world Jesuit in the story world.

I agree with Br. Guy and Jo Walton that James Blish did not seem to understand the actual arguments that would be made. Augustine wrote of alien creatures in The City of God. (He said if they possessed intellect and volition, then they were human, no matter their shape or color. And when in the Summa Theologica Aquinas wrote of new species arising long after the “days of creation,” he suggested material causes, not divine poofing. (They were the wrong material causes; but they were reasonable, given the science of the day.) Augustine, of course, pointed out that in Genesis, God gave the earth the power of bringing forth new forms of life, and that the earth did so. This was causal, he wrote. IOW, matter possessed its own inherent (natural) powers of causation.

But I digress.

Revealing my ignorance:

“Christian-avant-le-dieu morality” — I Googled this phrase, and found only this post.

“Chretien avant le dieu” gets me zip.

I gather that the idea is “Christian morality without benefit of actual Christian faith “, but is this your own coinage or a reference I have totally missed?

I don’t think that A Case of Conscience necessarily takes place “in a universe in which Christian theology as Blish imagines it is explicitly true”; it’s just that the theology is never shown to be false. The novel is an agnostic’s two-sided vision, right down to the last plot-turn. “Yes, and No” in the words of the Joycean joke Blish hardwires into the opening section of the novel.

There’s a lot of good stuff in the book. One of my favorite bits is the scene where Agronski’s damnation is sealed (or he comes to an existential crisis from which he can’t recover) because his favorite TV show has been cancelled. I wonder if JB thought about this when he was one of the literary custodians of the Star Trek universe…

I hadn’t really thought about this book since I read it in a science fiction class back in the 70s. Now I’m going to get a copy to place on my to be read pile. I wonder if this book , or the discussion of it in that class, was a root element of an idea I came up with to try to justify the idea of aliens with the ‘Made In God’s Image’ belief. This may be going off topic but I see this as a chance at figuring out where this idea came from.

First. How this came about. I had some free time that day so I was sitting in one of the lounges (at Webster College) reading a story from James White’s The Aliens Amoung Us. Another student came in and the following conversation took place. (As close to the wording as I can remember.)

Other student “I noticed the book you’re reading. Let me ask you this. Do you think there are any aliens out there?”

Me “Yes. I do.”

“Do you think they would look anything like us?”

“No. Given the wide variety of life on this planet, I’d think it unlikely that they’d look like us.”

“Well. Then. I’d like for you to consider this. You’re wasting your time reading this stuff. Even you think that they would not look like us. And if they don’t look like us, that means they were not created in God’s image so they are not worth your thinking about them.”

To this day, I’m still baffled as to where this next bit came from but I replied with the following.

“I think you are wrong. I think they could look nothing like us and still have been made in God’s image.”

“How do you mean?”

“Well. Think of the universe as a funhouse hall of mirrors. In a hall of mirrors each mirror was made by a man. When the man stands before each mirror his reflection looks different from that in the other mirrors. Each image vastly different – conforming to the properties of that mirror – but each still an image (reflection) of the man. Now. Consider the Creator creating the planets in the universe. Each planet is different. When the Creator stands before each planet the reflection cast upon that planet conforms to the planet’s properties but that reflection is still in the image of the Creator.”

He looked at me as though I had just committed blaspheme and I don’t think he ever spoke to me again.

Many years later while composing a letter I remembered that conversation. The act of composing that letter and remembering that conversation were two of the things that led me to try my hand at writing. The writing part is coming along but the getting published part still needs work. Anyway, I can’t deny that this silly idea has left an imprint in my approach to storytelling.

I also want to say that I found Brother Guy’s points well thought out and well put. He has given me some things to think about. I’m saving a copy of his comments and I’ll look back on them after I’ve re-read this book.

The three books: Doctor Mirabilis, A Case of Conscience, and The Devil’s Day (= Black Easter + The Day After Justice) form a trilogy, said Blish, to which he gave the title, After Such Knowledge. The books of Knowledge are unified by a questioning of the ethical validity of secular knowledge. The theology Father Ramon falls back into despite his education, perhaps as a result of the shock of encountering an apparently unfallen race, is a working-class conservative Catholicism of the 1950s, not the best of Catholic thought—it may be that Blish grew up with it. Blish himself was educated as a biologist: it is not hard to imagine Father Ramon’s character as influenced by Blish’s response to his education.

I also think the four human explorers of Lithia represent four different approaches to life, probably on the model of a Jungian quadriplicity (Blish seems to have studied and respected Jung), or perhaps even four sins, like the four major characters of The Devil’s Day. They seem unrealistic because the are unrealistic: they are aspects of humanity, not whole people. Both works, I speculate, may be profound and subtle allegories. The insanity of the times described in Conscience may be a reflection of Blish’s take on the insanity of the 1950s. They are not, when one thinks about them, so very much crazier than our own times: someone born in 1980 might similarly find 2015 insane.

Ludon, Blish directly addressed the subject of the human response to the appearance of aliens in his essay, “A New Totemism?”

Correction: if Blish grew up with a conservative Catholicism, it would have been in the 1930s, since he was born (says WikiP) in 1921.

Hapax: Sorry. There’s an expression “avant la lettre” meaning before the thing itself, or before the word was coined, so you could say a C.17 theory of psychology was “Freudian avant la lettre”. I meant by my expression to imply seemingly Christian “before (hearing about) Christ”. It was one of those things that seemed clever when I wrote it but it actually really stupid because it’s unclear and therefore hinders communication — I really hate it when I do that.

I read A Case of Conscience decades ago, Jo, and remember only one item about it: I liked it. I have intended to re-read the book for a few years now, but wonder whether I would like it as much today, after reading your review.

The thing is I like books like this: they offer a (sense of) gravitas the typical extruded fantasy merely drafts, if even. I admit I also enjoyed Russell’s The Sparrow, for its examination of religion and theology, and especially for its human (foibles and fallibilities) characters. But ‘idiot characters’…? (To borrow from Damon.) Hmm, I guess I must re-read both novels!

Thank you, once again, for writing such an intelligent and literate post. And the high level ‘conversation’ that ensues. In some ways, your posts and their resulting conversational threads are better than the books.

Thank you, too, for sharing the letter from Brother Guy. Many people complain the art of letter writing is lost in (to) the ether. Not at your home! Fascinating thoughts, too.

Okay, all done thanking you. :-)

Oh, before I forget, congratulations (again!) on your conversation in this week’s issue of Publisher’s Weekly. (You must be a favored child or teacher’s pet of the magazine. :-) Anyway, your new novel interests me, based solely on that conversation. Off now, to determine its lay-down date.

*sigh* I must be the only person who loathed both A Case of Conscience and The Sparrow (not for quite the same reasons, though). Regarding A Case of Conscience: if a science fiction author is going to play fast and loose with science, history, theology and logical reasoning in general and expect their readers to let it slide, they’d better keep them reading with compelling characters, peerless prose or the like. And Blish clearly succeeded—except for a minority of ungrateful nitpickers like myself.

That said, this is an amazing post. Bookmarked for future reference.

(JamesEnge: I thought “Yes, and No” could perhaps also be a reference to Sic et non? Dammit, I’m going to have to re-read ACoC after all…)

Jo @@@@@ 2: I read Dr Mirabilis – though a very long time ago – and there is nothing in it explicitly and necessarily fantastical. However, one of its strong points for me was the good job Blish made of showing everything through the eyes of a man from a pervadingly supernaturalist culture. Yes, Bacon is a rationalist; but he’s portrayed as a rationalist from there, not from here…

For me, Part 1 of A Case of Conscience works considerably better than the remainder of the book. I think because it is a case of discovery and provides a picture of a truly alien culture and the way we, as humans, relate to it. That is what makes SF so interesting to me, the ability to look at something foreign and decide if we see a reflection of ourselves or something totally different.

In the first part of the book, I saw something different, but in the second half of the book, I saw ourselves… and it wasn’t a very pleasant reflection.

Does it provide a correct account of Catholic theology? I’ll leave that up to others better qualified than I am to decide.

A quick word on The Sparrow, too. I recall some criticism that it wasn’t really SF because Russell isn’t really a science fiction writer. I’ve heard that about other writers, too, and disagree. That’s an unfair criticism of any book.

The thing that bothered me most about A Case of Conscience while reading it was how abusively raised Egtverchi was. No wonder he grew up twisted.

It was one of those things that seemed clever when I wrote it but it actually really stupid because it’s unclear and therefore hinders communication — I really hate it when I do that.

Don’t. Look at the result: your reader was forced to do some research, which can never hurt, and, in your explanation learned something he didn’t know before.

No reason to apologise for making people work a bit with an occasional bon mot like that.

Nolly: I agree. He was supposed to grow up unnurtured, but in an environment with others of his kind and dangerous animals, not entirely isolated like that. No wonder he ended up hating everyone.

Been a long time since I’ve read it, but I remember being blown away by Blish’s novel. I always meant to follow up on this author, and have had Cities in Flight on my shelf for awhile.

Some general thematic similarities to The Sparrow, though for my money that novel was a lot more impressive than Case of Conscience.

I agree with James Enge: Blish leaves it open, right down to the ending, as to whether or not the presented theology is true.

I didn’t see the Catholic theology in the book as an attempt to depict real-world Catholic theology; it was a speculative future RCC that had taken a radical hard-right turn sometime in the 2oth or 21st century (the “Diet of Basra” bits imply that). He certainly didn’t foresee Vatican II. Even today’s more conservative Church really isn’t like that, but some of the little splinter Catholic movements may be.

But the nastiest character in the book is a secular physicist. As a physics student I bristled at that a little.

I’ve read them all, and I thought of Dr. Mirabilis as somewhat fantastical; but it’s been a long time, and that may simply have been the effect in my head of a straight historical novel about a man who was a rationalist by the standards of the time — but probably came far closer to believing in actual magic than I ever have.

One thing that seems fairly common (I hear stories all the time) is for individual Catholics, including priests, to have very fixed ideas about “doctrine” that simply aren’t true (people describing weird stuff they were taught in Catholic schools happens a lot; though of course they could always have misunderstood). It makes no sense to portray the priest in the story as working contrary to doctrine (until we come to the part where the situation overwhelms him and he starts to break down, anyway), but Blish may have gotten his ideas from such a priest.

Or it could just be typical sloppy research.

In fact, I’ve encountered that too: a friend of mine once told me he’d been taught young-earth creationist ideas in a Canadian Catholic school whose staff was seemingly unaware of church doctrine about this.

One audio book edition of A Case of Conscience includes an amusingly snippy foreword by Blish in which he defends the ways he chose to imagine how Catholic doctrine would change 100 years in the future.

I liked how Blish handled Ruiz-Sanchez’s approach to religion. He treats questions of religious doctrine sort of as if they were jigsaw puzzles.

The ending is disturbing in a way that makes me want to write a story “responding” to it, which is kind of a fun feeling to have.

Brother Guy Consolmagno said, “The classic definition [of soul] is ‘intellect and free will’. … Freedom immediately demands the possibility of … making a choice you know is morally wrong. So how would you know that a race of creatures that didn’t ‘sin’ was even capable of sinning? If they are utterly incapable of sin, they are not free.”

That’s an interesting definition and assertion, because for some, it would imply that God is not free. I had a Evangelical professor once tell me that God is incapable of sinning because it’s not in his nature to do so. If you combine that with Consolmagno’s definition of ‘soul’ and ‘free,’ then you’d come to the odd conclusion that God is not free or does not have a soul. I’d be interested in hearing the Jesuit and the Evangelical discuss that.

That got deep in a hurry. I’ve learned as much from the thoughtful comments as I have from the excellent review and the shared letter from Brother Guy Consolmagno (how I’d love to hear or read his thoughts on Eco’s _The Name of the Rose_, _Baudolino_, or even his thoughts on the published correspondence between Eco and Cardinal Maria Martini).

I hesitate to wade into such deep waters for fear of accidentally slighting either Blish’s legacy or the RCC’s centuries-long mission of providing universal teaching. I also fear showing my ignorance in such a remarkable discourse. I’m a simple former military enlisted infantry/mp type and a passionate self-taught man, with all the weaknesses that come with that.

Self-effacing disclaimer concluded, I think a gentle reminder from the peanut gallery can sometimes be useful. History may be important here? This galleried peanut would like to remind the group of what I know this crowd already knows. That is; Blish’s career was often unabashedly oriented towards providing commentary on the social wars of his day. He also spent substantial energy publishing commentary directed against the wilful ignorance of science by writers and critics alike. In effect, Blish was something of a player in the post colonial period of rapid social change which took place in the 1950s through the 1970s.

In turn, Brother Guy’s thoughtful apologia may be a bit optimistic, historically speaking, and also a bit shaped by the world that has emerged in the years following the era of epic space operas and the battles against concepts of race and gender shaped by colonialism and world wars. A bit contemporary to this time. But see? There I go. I don’t want to even begin to critique the letter from Brother Guy. The military person in me quietly revolts to call a thinker like him, “Brother.” Too familiar. I’ve saved his letter to read and re-read.

Thanks for this review and the comments. Time for me to dig out a copy of _Dr. Mirabilis_ again!