Thomas M. Disch was born in Iowa, but both sides of his family were originally from Minnesota, and he moved back there when he was an adolescent. Although he only lived in the Twin Cities area for a few years, the state left an impression on him, and between 1984 and 1999 he veered away from the science fiction for which he had become best known to write four dark fantasy novels which have become collectively known as the “Supernatural Minnesota” sequence. The University of Minnesota Press recently republished the entire quartet, and Beatrice.com’s Ron Hogan has set out to revisit each novel in turn, starting with The Businessman and continuing onwards.

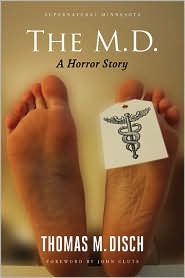

If, as suggested earlier, The Businessman matched the intensity of early Stephen King novels like Cujo, The M.D.: A Horror Story (1991) is perhaps comparable to a slightly more expansive tale like The Dead Zone—except that Billy Michaels, Disch’s protagonist, is both Johnny Smith, trying to come to terms with his strange powers, and Greg Stillson, destined to plunge the world into catastrophe.

When a nun at a Catholic school in the Twin Cities teaches her kindergarten students that Santa Claus isn’t real during an early ’70s holiday season, Billy refuses to accept this, and runs away from school rather than report to the principal’s office. He hides in a nearby park, where we learn the reason for his obstinacy: Santa does appear to him in visions, and when Billy complains that Sister Mary Symphorosa said he was just a pagan god, he replies, “Well, I suppose I am in many ways.” Later, when Billy’s father confirms the truth about Santa, this god simply announces that he’s also Mercury, and promises Billy to reveal where his older step-brother has hidden the “poison stick” he created by “tying the dried corpse of some kind of sparrow to the end of a strange twisty doubled-up stick”—a parody of Mercury’s caduceus, the symbol of the medical profession.

If Billy is willing to swear loyalty to Mercury (“Now I lay my soul in pawn”), he can use the caduceus to dispense health or disease to others, and there’s no doubt where his interests lie: “I want to know how to use the stick. The poison stick that makes people sick.” Disch could have presented readers with a tragic figure; Billy might have wanted to use the magic of the caduceus to make the world a better place and been corrupted by his evil. But The M.D. is all the more horrifying for its emotional authenticity. Even as a kindergartner, Billy has plenty of greed and malice accumulated in his heart, and the dark god doesn’t need to push him very hard to let it out.

His initial attacks are accidental—a curse intended for some neighborhood bullies turns his stepbrother into a vegetable; a practical joke to make his father’s hair fall out winds up afflicting his grandmother—and he even casts the caduceus aside for several years. (He may be greedy, but he still knows guilt and fear.) In 1980, however, the more mature William learns to focus its power, balancing the good health he desires for his family members with both brutal vengeance on those who have slighted him—as with the teacher who tries to keep him out of an early-acceptance college program and is afflicted with Tourette’s—and vaster, more impersonal devastation—beginning with a lighter belonging to an obnoxious co-worker of his stepfather’s which William turns into a dispenser of lung cancer to anyone who uses it.

?Finally, William creates a plague called Acute Random Vector Immune Disorder Syndrome (or ARVIDS, “for which AIDS had merely been an appetizer”) which only he can cure. The caduceus spells must be spoken in rhyme, and for this William creates his most elaborate poem yet, a nine-line verse that incorporates a delay of several years so that, as an adult doctor, his healing abilities will seem more plausible when the curse finally kicks in. Thus the final section of the novel takes place in what was for original readers the near-future of 1999, where William is profiting both through his medical research center and by investing in quarantine facilities that have been built around the area. It’s the closest thing to a science fiction element you’ll find in The M.D., or anywhere else in the Minnesota novels, but Disch plays it subtly, dropping occasional hints about how the world had changed in the nearly 20-year gap in the narrative. Very few of these then-futuristic elements come across as dated; William spends much of his time in a virtual reality that made seem crude compared to today’s multiplayer online game environments, but still within the realm of plausibility. About the only thing Disch “got wrong,” if you want to put it that way, was to overestimate the momentum of the African American Catholic schism of the early 1990s, and even that you can rationalize as one of the possible side effects a devastating plague would have on society.

?As William’s comeuppance approaches, it becomes increasingly clear that The M.D. takes place in a moral universe much like that of The Businessman, though Disch doesn’t interject as the narrator to explain the principles as he did in the first novel. What he does do, however, is lay several clues that the two stories actually take place in the same version of the Twin Cities. The Catholic school is attached to the same parish where Joy-Ann Anker worshipped in the first novel, and the same priest plays a small part in both stories. (Likewise, the therapist who treats William’s stepsister for anorexia is the same one who treated Bob Glandier.) But the connections are tighter: Disch reveals that William lives next door to the Sheehy family, who came to such a spectacularly bad end after their own son (“a few years younger than William”) is possessed by another evil spirit.

(Still, it’s a bit surprising that William’s ultimate demise should mirror the destruction of the Sheehy family so closely—both climaxes occur in a burning home which is still not enough to fully extinguish the evil that’s been unleashed. Does anybody know if such an event held significance for Disch? Because this isn’t the last time it’s going to happen, either.)

The M.D. turns out to be a much bleaker story; there is no happy ending for the handful of survivors as there was for Joy-Ann’s son (and the ghosts of John Berryman and Adah Menken) at the end of The Businessman. Although the epilogue hints at a medical explanation for why Billy was such an easy target for Mercury’s schemes, the evil is also clearly seen to exist outside his genes and, in the final scene, is poised to re-enter the world even as the effects of his curses start to recede.

Ron Hogan is the founding curator of Beatrice.com, one of the earliest websites dedicated to discussing books and writers. He is the author of The Stewardess Is Flying the Plane! and Getting Right with Tao, a modern rendition of the Tao Te Ching. Lately, he’s been reviewing science fiction and fantasy for Shelf Awareness.

I am trying to avoid spoilers, but I seem to recall that the mass market edition inserted the wrong conjunction into a line of Disch’s poetry — “father brother and son” — which I hope the University of Minnesota Press has corrected? If they haven’t, you’ll know why if you replace the ‘and’ and squint.

(For years I hadn’t seen an editorial error which wrecked the meaning of a passage quite so badly until Gene Wolfe’s The Knight. So Disch is in excellent company.)

Of course, it’s been a very long time since I’ve read it, and it might have stuck in my mind because it’s a plot point.

(The Wolfe error, though, that was a doozy.)

Carlos, you’re right; I remember being confused by the “and son” thing.

Unfortunately, the recent trade paperback of 334 included some unhelpful “corrections” too, e.g. “gorilla” -> “guerrilla”.

And we know it’s an editorial mistake because [spoiler]. dammit, what a thing to screw up.

I liked these books a lot. Disch was clearly trying to capture some of the energy of popular horror novelists — I agree, I think it’s specifically King — but he was writing them for an audience that would appreciate his humor, which could be dark, sour, and even cruel, especially in places where a casual (or fannish) reader might have expected comfort. A little like people turning on Jay Leno and finding Michael O’Donoghue on instead.

I don’t continue the King analogy in the other two essays coming up, but if I did, I think I would say The Priest is the Richard Bachman novel.

I didn’t find the right poem in a quick flip through the pages, but if one of you wants to rot13 whereabouts in the novel it should be, I can double-check; I’m afraid I don’t remember whether it came out right or not (although my first impression of the text is that it looks an awful lot like 1990s Knopf typesetting).

Ron: It’s not a poem, it’s qvnybthr fcbxra ol Zrephel va gur zvqqyr bs puncgre fvkgl: “–Naq bs oebnqre qnatref pbagvatrag hcba gur svefg, qnatref sebz sngure, oebgure, be fba.”

Ah. Yes, the line in question still says “and.” Although I’m wondering if that ISN’T a mistake, in that Ynhapr, Arq, and Whqtr might all be seen as contributing. (Or, if Ynhapr seems a long shot, consider the letter.)

Ron: True… however, I remember an interview where Disch was asked about the significance of a certain character’s name, and he quoted that line– and I’m pretty sure he quoted it the way Carlos thought it should be, so that the pun was explicit. (But he also said something like “What else could it be? It’s not as if there are any science fiction writers with that first name…”)

Oh, wait: DAMN. The two by four has just hit me on the head. Sorry that took me so long.

Yeah, it went right over my head at first too, and not just the first time. So did the significance of William curing a certain guy in the last section of the book – Disch doesn’t offer any explanation of what that has to do with the unraveling of his power (whereas, say, Stephen King would’ve put big flashing lights on it), but if you think back to the beginning of Billy’s career it makes perfect sense – really lovely plotting.

(Also, aha: here’s that interview, which is great.)

And, and, and… THAT is exactly the thing Mercury was talking about, and I didn’t realize it until you just mentioned it. Although I’m curious: It really ought to have only one specific consequence (which it does have), and not the wide-ranging effects it does.

Oh MAN. And you’re right: Disch totally just slides it in there, even fakes you out by making you think William HAS evaded the problem, and that’s just brilliant.

OK, I’ll bust out the ROT13 again because if I talk about this cryptically enough to avoid spoiling it for others, there’ll be no way to tell whether we’re talking about the same thing or not:

Urnyvat Ohool haqvq gur “or yvxr Ohool” phefr ba Arq, juvpu jnf Ovyyl’f svefg phefr. Gur pnqhprhf pna bayl tnva cbjre ol uhegvat crbcyr, fb rirelguvat Jvyyvnz qvq jvgu vg nsgrejneq jnf ranoyrq ol gung svefg npgvba; haqbvat gung bar ibvqrq gur jneenagvrf ba gur erfg ergebnpgviryl. Ur arire unq gb jbeel nobhg fhpu n guvat orsber, fvapr cre Zrephel’f ehyrf gur pnqhprhf pbhyq arire urny n crefba vg unq unezrq– ohg ur nppvqragnyyl sbhaq n ybbcubyr, ol urnyvat fbzrbar ur unqa’g phefrq ng nyy ohg unq hfrq nf n ersrerapr cbvag sbe gur phefr.

In my opinion.

That sounds like a solid interpretation, and as you say, points to Disch for NOT putting a big flashing light on it.

Things like this are one of the reasons I was psyched to do these reviews here, where they’d be a springboard for discussions where other readers could fill in the stuff I missed. And that’s worked out REALLY well this week.

Cool!

One last thing: that exact wording, “father, brother, or son,” is very commonly used in medical history questionnaires, patient education pamphlets, etc., when discussing heritable conditions that could show up in a close male relative. I can easily imagine Disch reading the phrase in a doctor’s office and getting it stuck in the wordplay center of his brain.