There’s an old saying: “God writes lousy drama.” It’s very familiar to anyone who writes historical fiction in any capacity, and even if you’re an atheist, it’s still apt. The idea is that you can’t write most stories exactly as they occurred (to the extent documented, that is) because even riveting history can make for a dull book or play. Writers can derive a lot of comfort from this saying, because it offers a certain amount of carte blanche to alter history as needed to suit a narrative. Of course, you can also run into trouble if you start thinking it lets you off the hook when it comes to complicated history and research.

I happen to love research (most of the time) and am proud of my history geekdom. Whatever I’m writing, I tend to prefer historical settings because the past can illuminate so much about the present—and about ourselves. I also like the clothes. So whether I’m writing something serious or funny, fantasy or no, I tend to dive into the past. Additionally, not to sound like a vampire myself, it also gives me no end of subject matter to pilfer. I have a ridiculously good time taking history and playing with it—all respect and apologies to my former professors, of course.

As much as I love the hard work of the research, when I begin a new project, it’s very much the characters’ stories that come first. My main service is to them and their journey. If I don’t tell their truth, it doesn’t matter how historically accurate or interesting I am—the story won’t feel true. (Or keep anyone awake.) So in the early days of crafting a piece, I concentrate on the characters and their emotional arc.

After that, the history and emotions run neck and neck because the dirty secret is that there is absolutely no way I could pretend to tell a true story about a character in a given period if I did not know the true history. Or rather, I could pretend, but everyone reading it would see right through me and would—rightly—flay me for it. So you could say the research both helps me get at the truth and keeps me honest.

It’s usually at this point in the process that I begin to get contradictory. I feel it incumbent upon myself to be historically accurate (getting two degrees in the field will do that to you) but I also don’t like to be slavish to exactness. Going back to the point about God writing lousy drama, it just doesn’t serve anyone to let the history overtake the narrative. So it becomes a balancing act. That is, I try to stay as absolutely accurate as possible, but don’t lose sight of what’s really important. Every now and again I have to remind myself—this is not a thesis, it’s fiction.

Which is much easier to remember when it’s vampires in the midst of World War II. In this instance, I’m definitely reinventing and playing with history—and enjoying every minute—but I often feel as though the onus to be accurate in every other aspect of the work is that much heavier. Fiction it may be, but I want it to feel real both for myself and my readers.

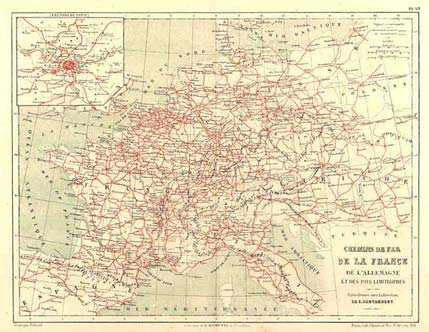

One thing I have found in the research process is how it can really bog you down if you’re not careful. One of The Midnight Guardian’s three narratives follows a train journey from Berlin to Bilbao and I spent ages trying to find the exact route, including stops and schedules. At some point—it may have been when a librarian was throttling me, I don’t remember—I realized that I was tying myself up in a knot trying to find details that ultimately didn’t further the narrative. I wanted to have all that information, but having it would not have improved the story. So I did something that is not always easy for me and let it go.

I think letting things go can be difficult for a lot of writers of historical fiction. There are two problems—what you don’t find, and what you do. When I was buried in books, maps, and papers studying Berlin and the war from 1938-1940, I found any number of details and stories that I thought would be fun to weave into my characters’ narratives. I even wrote quite a few of them. But as I was refining the manuscript, I came to the hard realization that, cool though a story might be, it didn’t necessarily work with my characters and so out it went. It was one of the hardest things I had to do—but the nice thing about writing is that no one sees you cry. Besides, when the story ends up better, there’s nothing to cry about anyway.

Sarah Jane Stratford is a novelist and playwright. You can read more about her on her site and follow her on Twitter.

Going back to the point about God writing lousy drama, it just doesn’t serve anyone to let the history overtake the narrative. So it becomes a balancing act. That is, I try to stay as absolutely accurate as possible, but don’t lose sight of what’s really important. Every now and again I have to remind myself—this is not a thesis, it’s fiction.

This: yes!

I realized that I was tying myself up in a knot trying to find details that ultimately didn’t further the narrative. I wanted to have all that information, but having it would not have improved the story. So I did something that is not always easy for me and let it go.

Yes, to this, too.

Actually, I’m just going to point to this entire essay and say, “Yeah, what she said.”

“After that, the history and emotions run neck and neck …” Hmm, maybe you DO sound like a vampire.

Teasing aside, you make a very valid point about how the history bits need to tie to the story’s emotion and meaning for the reader to appreciate them. Sometimes an author can get too drawn into the research. One example is Taylor Anderson’s Destroyermen books, in which a number of plot events revolve around the historical problems that the US Navy had with torpedoes in the early years of WW2. While the military history geek in me enjoyed the references and the details, the more critical reader in me wondered if they were too distracting and not truly necessary to the story of displaced folks from “our” WW2 on an alternate Earth where the meteorite apparently did not take out the dinosaurs 65 million years ago and was about to have its own world war.

And, of course, if the story works, the research (or lack thereof) is likely to be ignored, as shown by Conan Doyle’s “Adventure of the Speckled Band”, one of the most popular Sherlock Holmes stories, which demonstrates that Dr. Doyle knew little about snakes (No, they do not respond to whistles. No, they cannot climb up a free-swinging piece of rope.) but a lot about writing an exciting, involving mystery.

I always admired my late friend Terry C. Johnston’s way of writing historical fiction, especially in his The Plainsmen series. He mixed one or two fictional characters into the real events, among the real participants. The events were told as the participants described them in letters and memoirs, so that Johnston’s novels had the feeling of authenticity.

I’ve extensively studied the Indian wars of the Old West (and the Old East), yet I learned a lot while following Seamus Donegan through the aftermath of Fetterman’s defeat, the Wagonbox Fight, Beecher’s Island, Summit Springs, the Lava Beds, Adobe Walls, the Rosebud, and beyond. I think Johnston hit on the perfect formula for how to construct at least one type of historical fiction.

I have to agree with Ian and Sarah Jane. I haven’t dealt with this in terms of history, but in terms of accurate depictions of the real world? Hell and yes.

Installing Google Earth was probably the worst thing I have ever done in terms of writing tools, because I now know – in excruciating detail – the entire coastline of Bali because I decided it would be nice to model a nation after it. And then I had to find a place to put the cities. And my character’s neighborhood. Oh, but another character comes from “real” world Edinburgh to “otherworld” Bali. Where is his flat going to be in Edinburgh? And where should he work? Does he take the bus or drive? No, wait, let’s move him to London. What Underground does he live near? Should I put him near Green Dragon Alley? No, maybe near Kensal Green. And on and on ad infinitum.

Having your own spin on events is a natural thing in terms of what each individual person will persive and interpret from information given but most concutions should be the same. In any and all cases is information worded different but most tend to have the bases of the findings similar.

My current WIP has foundered in the sands of extensive research on Zoroastrianism, Kshnoomi Parsis, Pashtuns, history of the Sistan basin, and collection of dictionaries for Hindi, Gujarati, Pashto, Farsi, and Baluchi. Also much use of Google Earth for views of Kuh-e-Khwaja and Bust.

In his latest three books, Drood, The Terror, and Black Hills, Dan Simmons has an uncanny ability to mix historical characters and minute historical details into his work to the extent that you (or at least, I) find myself heading for the bookshelves, library, and/or Wikipedia frequently as you read.

He has a fascinating article about trying to weave history together and craft a story in the gaps on his web page (starting mostly around the “Five of Hearts” subheading).

I think that if you want to play fair with historical characters without creating a complete alternate history, you usually have to fill in the gaps of their documented life or show something novel inside their heads.

I’m about halfway through Kim Stanley Robinson’s Galileo’s Dream and it is having the same effect. I’m enjoying the semi-historical parts about Galileo more than the SF elements, although the sequences where Galileo learns 1400 years of math and physics are fascinating. Even if all of the exact details aren’t correct (although I suspect most of them are, to the best of his research ability and subject to the paradox aspects of the story) and although I was pretty familiar with Galileo’s life and accomplishments, I feel that I understand the context of his life better through this story. By the way, there is nothing wrong with the SF part and I understand the literary style he is going for, but I think I would have enjoyed the historical part on it’s own.

This was an interesting read. I too love the research into history for my writing. I try to answer “should medieval fantasy be historically accurate?” And though, for the sake of creativity, the easy answer is “no,” my soul begs to scream “yes!” There’s not many writers like us. In my opinion it’s a good trait, and something civilization desperately needs more of!