The Broken Sword was first published in 1954, the same year as the original publication of The Fellowship of the Ring, so it’s a pre-Tolkien fantasy, and certainly a pre-fantasy boom fantasy. Lin Carter, who is one of the people who created fantasy as a marketing genre, feels the need to go on about this at great length in the introduction to the 1971 revised edition, because Anderson used the same list of dwarves in the Eddas that Tolkien did and has a Durin—this would be more convincing if Durin hadn’t been mentioned in The Hobbit (1938) but it really doesn’t matter. The Broken Sword is indeed entirely uninfluenced by Tolkien, or indeed anything else. It has been influential, but the most interesting thing about it is how unique it still is.

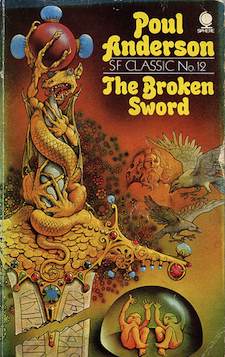

First, this book is grim. No, it’s grimmer than that. Grim for Norse levels of grim. The truly unique thing Tolkien came up with was the eucatastrophe—where the forces of evil are all lined up to win and then the heroes pull off a last minute wonder and everything is all right. He took the looming inevitability of Ragnarok and gave it a Catholic redemptive spin. Anderson stuck with Ragnarok. There hasn’t been anything this grim in heroic fantasy since. There’s kinslaughter and incest and rape and torture and betrayal…and yet it isn’t depressing or gloomy. It’s also very fast moving, not to mention short. My 1973 Sphere edition, which I’ve had since 1973, is barely over 200 pages long.

No actual plot spoilers anywhere in this post!

The second deeply unusual thing is that it takes place on a whole planet.

The story is set in Britain, with excursions to other bits of Northern Europe, at the end of the tenth century. It’s also set in Alfheim and other parts of faerie that lie continent to our geography. So far so normal for fantasy set in our history, oh look, Europe. But unlike pretty much everything else I’ve ever read that does this, Anderson makes it all real. Faerie has countries too, and while the elves and trolls are at war here, there’s a country over there with Chinese demons who can only move in straight lines, and one with djinni, and there’s a faun homesick for Greece. I am always deeply uncomfortable with fantasy that takes European mythology and treats it as true and universal. What Anderson does is have mentions of other parts of the real world and other parts of the faerie world. He knows it’s a planet, or a planet with a shadow-planet, and he makes that work as part of the deep background and the way things work. He’s constantly alluding to the wider context. Similarly, all the gods are real, and while what we get is a lot of Odin meddling, Mananan also appears and Jesus is quite explicitly real and increasingly powerful.

I loved this book when I was eleven, and I still love it, and it’s hard to disentangle my old love from the actual text in front of me to have mature judgement. This was a deeply influential book on me—I don’t mean my writing so much as me as a person. The Northern Thing is not my thing, but this struck really deep. I probably read it once a year for twenty years, and the only reason I don’t read it often now is that when I do that I start to memorize the words and I can’t read it any more. I can certainly recite all the poetry in it without hesitation.

The story is about a changeling—both halves. Imric the elf takes Scafloc, the son of Orm, and leaves in his place Valgard. Scafloc is a human who grows up with the elves, and Valgard is half-elf and half-troll, and he grows up with Scafloc’s human family. Doom follows, and tragedy, especially when they cross paths. The book is about what happens to both of them. The elves and trolls are at war, though some suspect the Aesir and the Jotuns are behind it. There’s a broken sword that must be reforged, there’s doomed love, there’s Odin being tricksy. There’s a witch. There are great big battles. There’s skinchanging and betrayal and magic. Even the worst people are just a tiny bit sympathetic, and even the best people have flaws. This isn’t good against evil it’s fighting for what seems to be the lighter shade of grey, and people trying to snatch what they can while huge complicated forces are doing things they can’t understand.

Fantasy often simplifies politics to caricature. Anderson not only understood history and the way people were, he made up the politics of faerie and of the gods and got them as complex as real history. I read this now and it’s all spare prose and saga style and he does so much in the little hints and I think “Damn, he was good! What an incredible writer he was!”

If you haven’t read it, you should pick it up now while there’s such a pretty edition available. If you have read it, it’s well worth reading again.

Jo Walton is a science fiction and fantasy writer. She’s published two poetry collections and eight novels, most recently Lifelode. She has a ninth novel coming out in January, Among Others, and if you liked this post you will like it. She reads a lot, and blogs about it here regularly. She comes from Wales but lives in Montreal where the food and books are more varied.

I always thought this book came out after lord of the rings. That took place in the fourth age of man. Do know if the mermaid stories Poul Anderson wrote are they after the fourth age or are they indepenenet of Lord of the rings also.

I am always deeply uncomfortable with fantasy that takes European mythology and treats it as true and universal.

Yes. This. Will have to check this title out. Thanks as always for the beautiful review!

PhoenixFalls: I feel confident you’ll like it.

I am always deeply uncomfortable with fantasy that takes European mythology and treats it as true and universal.

Are you deeply uncomfortable with fantasy that takes Chinese or African or any other mythology and treats it as true and universal, or are you just terribly politically correct, like the rest of Tor.com?

Scotty21, show us some in print and well written fantasy in English that does those things and then we’ll have a conversation. Until then, go back to your mead hall.

This is a terrific book, and I felt showed a fascinating byway that mainstream fantasy could have followed further, but didn’t. Who knows, perhaps it will come back the way the more Conan-influenced stuff has in the 2000s.

I’m deeply uncomfortable with State Shinto but that may be a matter of my own age and experience. I don’t much like Lost Legacy either.

Amber may be universal but not true – highly unreliable in fact – so it’s OK to be comfortable there. Zelazny swings from Lord of Light to Cats Eye and each I think good art.

Mostly though it’s a matter of bad art I think. A trickster be it embodied in a spider, a coyote or Loki approaches a universal but may not be what I mean by true at least in the sense of refutable.

Seems to me somebody in the broad community just wrote of the language and usage issues in speaking of gremlins with a Tibetan Buddhist – many myths carry implied assumptions that may not travel well.

Fortunately for my own view of true and universal European myths I was impressed more by the constant inserts of some say by Robert Graves in his (southern European) Greek Myths than by either their truth or universal application. On the other hand I considered a good deal of Graves – sadly not so much his SF genre – to be fictional but good art. Maybe Harold Shea was visiting pocket universes with in-universe truths but with some logical constants in common?

#8 – Maybe Drake’s Northworld trilogy pushed along the same paths? Drake considered pushing on to Ragnorak and decided to stop short.

Likely resources like the pair of books on weapons and Icelandic stories of life in the Viking age by Dr. William Short that ESR is pushing will attract some. I have no idea how direct an influence such things might be beyond the occasional try for the Prometheus Prize by David Friedman et.al..

When I saw you were going to review The Broken Sword, I kep checking TOR to see it. This is a truly great book, and it’s a wonder that it manages to be fun to read despite being so grim. Perhaps it’s the spirit with which the characters face their fates.

This is a fascinating book. I read it for the first time recently because I’d never read much Anderson and so I simply grabbed a bunch of random novels off the shelf of a science fiction club library. I simply got lucky.

I’ll see if I can avoid spoilers too.

I can’t decide how much of the book is influenced by Tolkien (The Hobbit), as opposed to how much of it is influenced by the same stuff that influenced Tolkien.

I think the way in which elves, dwarves and trolls are distinct races with kingdoms and histories might owe a lot to Tolkien. The inclusion of goblins seems Tolkienesque too–there isn’t a really good reference anywhere in Saxon-Norse stories (that I’m aware of) that would have warranted ‘goblins’ in the northern fairy world (except perhaps if by ‘goblin’, was intended ‘ghost’).

But Anderson’s take on everything is just so wildly different from Tolkien, so much darker, so much, well, yes, more grim. Grimmer. Even perhaps Grimmr, if you’ll excuse the pun.

The elves keep slaves and aren’t many more shades of grey lighter than the trolls. They don’t slaughter people for fun (as the trolls do at one point), but there is a strong feeling that this isn’t any sort of ethical choice–it might be more of an aesthetic one. Or perhaps they just don’t find it as much fun. It’s not their thing, but they don’t strongly disapprove either.

The role-call of the elves of England, Cornwall, Wales and Scotland was wonderfully imagined and full of curious allusion. And yes, so too the references to the wider world of faries beyond Europe. It all comes together well, which is a big thing for any novel to pull off, let alone a first novel.

It’s a truely unique and interesting novel. I guess, if nothing else, I can attest that if you’ve never read it before, the Broken Sword still stands up well as a novel for a modern reader. I came to it with very little Poul Anderson under the belt, and I found it enthralling and different and hard to put down.

(Incidentally, the library version I read is the same Sphere edition as that pictured above, if a bit more beaten up by the years).

Christopher: Thank you so much for that comment, I was wondering about how it would be for a modern reader, and I’m delighted to see that it does hold up.

Nicholas: It took me a long time to write this post because of trying to answer the same question. I didn’t want to make it sound like a downer.

Very tentative since it’s been a while since I’ve read it, but maybe the reason the book isn’t depressing is that the characters don’t reflect on how bad their world is– it’s just their world, and they live as well as they can.

On the other hand, the same might be said of A Song of Ice and Fire, but it’s depressing.

This (in addition to your excellent essay) is an incentive to reread the book.

For a similar question, how does Heinlein manage to be a low-angst writer even when his characters are suffering quite a bit? For comparison, check out Charles Stross– he can do Heinlein style writing pretty well, but the emotional tone is very different.

A book that treats all mythologies as true? I’ve been looking for something like that. I didn’t realize it’d been published 56 years ago. To the library!

Anyone know a good place one could find this in the US?

CaptCommy: Uncle Hugos in Minneapolis.

Or you could try Abebooks online, which have used copies from $1. Or you could buy the British edition from Amazon.co.uk

scotty21@6

I choose option #2.

Even so, an interesting and informative review.

Just finished reading it for the first time. Do any of his later books take up the story of the sword and the child?

I discussed this book with Poul in 84 or so. He said in the forward that he wasn’t the same writer as he was when he wrote it and he would have written it differently if he had the chance. He didn’t disown it or anything. Just that he was a more mature writer and person etc.

I was twenty or so, so the Rainforest dad of long ago is not the same man as today so I understand him better now than I did when we spoke even though I don’t remember as much of what we discussed.

He and his companion, ( a younger author named S.M. Stirling) were alarmed when I asked Poul to sign the book to my son. I promised he would get the book when he was ready. And he did it remains one of his favorites.

The book was marvelous but the author did not enjoy it that much and to make him feel better I had him sign a copy of Three Hearts and Three Lions for my son as well. That was lost in a fire.

This book was full of life and blood and physical passion in all its forms. Whereas Tolkien was full of spirtual passion and was nearly chaste. Two very different drinks from the same well of myth and folklore. The Broken Sword makes a great chaser to Lord of the Rings and should be a movie as well.

Jo – are you the same Jo Walton who wrote “The Rebirth of Pan”?

As I was reading 2the Broken Sword” on the reccomendation of this review I kept flashing back to a story I had read last year. When I dug it out I saw the name and wondered if this was you and if so was “The Broken Sword” the inspiration for you in you writing your story?

The Not So Dark One: Two good questions. To the first, no, he never wrote any sequels to this, so the fate of the sword and the child remain unknown.

To the second, yes I am and yes it did. I think I mentioned that in the notes when I put it online? That’s in many ways the first novel I wrote after I was grown up, and there are a whole lot of things wrong with it, but definitely there are a whole lot of Broken Sword themes going on in it, as you so astutely noticed. Actually, it was also an influence on my first published novel The King’s Peace, because Odin is a character in that, and certainly my conception of Odin was certainly shaped by Anderson.

Thanks for the reply, just re-reading the Rebirth of Pan now, lot of themes similar (brother/sister etc.), but written quite differently. Can I just say I like how each of the characters has a slightly different writing style in their POV’s. Not sure if thats intentional (or even real and not just me being daft) but I like it.

I think that’s the same cover I have, though it seems unlikely I’ve got a British edition. Maybe I’m wrong, or maybe the art got reused. If I pull it to reread I’ll try to remember to come back with a conclusion on that.

I remember this only as part of his early fantasy, which I generically liked a lot. And which I have never that I can recall re-read.

Between my generically fond memories and your enthusiastic and detailed memories, I really should reread this (and perhaps some of the others) soon. Thanks!

(While we didn’t overlap here, Poul Anderson was a Minneapolis writer in the early days. In fact his mother lived near Northfield, where I grew up, and rented the old farm house on the land where an old friend of my father’s had built his new house. Despite none of the adults in my life much caring for SF then, they knew that Astrid’s son was an SF writer, and had written some of the books I was reading.)

The Not So Dark One: Yes, that was intentional, and I’m glad you like it. But nobody in their right mind would write a book with multiple first POVs that way, even if writing in first person was their top skill at the time. Crazily ambitious novel, and it nearly worked.

19-20 et.seq.

From an extended review by Michael Moorcock in

The Guardian for 25 January 2003.

Arguably the gist of the review is:

and arguably Anderson, perhaps depending on his personal black dog mood – for all I know most optimistic when personally most depressed but able to fight at least the sea steering a small boat – wrote books fundamentally at odds with each other.

David Drake does a nice tight third person in the voice of the focus character in his Isles series among other places – agreed that multiple first person might well give me a book to gnaw my foot off in order to get out – approaching the confusion of identity in such as The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldritch perhaps? Moorcock had a nice review of that in the Guardian as well.

I thought about putting a sic on the lower case I in inkling but perhaps that was a deliberate choice to generalize inkling as an adjective?

Wonder if, after Moorcock, it might well be a better chaser than appetizer?

Moorcock comes from a different direction than Tolkien. But his novels might make better movies. Moorcock sometimes reads like he was on major anti-depressants though LOL. His view is so grim it makes The Broken Sword look bright and cheery.

My 9 year old son asked the other day about “my favorite books ever”, and not having seen it since 1978 or so, I said The Broken Sword. I remember it as one of the most exciting stories I ever read. I was looking for a copy to get my boys when I found this page. Had no idea of its significance-glad to see it’s been as well loved by others as I found it.

Bob Babcock

http://www.unidatait.com/cloud-computing.html

I am always deeply uncomfortable with fantasy that takes European mythology and treats it as true and universal. What Anderson does is have mentions of other parts of the real world and other parts of the faerie world.

Thanks for mentioning that. I was looking forward to reading a historical fantasy based on Northern European belief, but if Anderson goes all multi-culti in this book I don’t think I’ll bother after all. I’d rather stick with Tolkien, the Sagas or Bernard Cornwell.