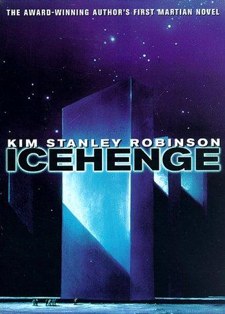

Icehenge (1984) is my favourite Kim Stanley Robinson novel, at least when I’ve just finished reading it. I first read it in 1985 as soon as it was published in Britain, picking it up because I’d been blown away by some of his short stories. Icehenge is incredibly ambitious and it really works, but its ambitions are very unlike what we usually see done in science fiction.

It’s set on Mars and Pluto between 2248 and 2610. It’s written in three sections, and all three are autobiographies—autobiography has become a popular genre in this future because with modern medicine everybody confidently expects to live about a thousand years. Unfortunately, memory is finite, so people only really remember about eighty years, with just occasional flashes of the time before that. Writing diaries and autobiographies for your future self saves them looking things up in the public records, and there might be things you want yourself to know about yourself that you don’t want to get into those records.

It’s not possible to discuss the weird cool things Icehenge does without some odd spoilers—to be specific, I can’t talk about the second and third parts of the book without spoiling the first part, and there’s also a spoiler for some odd things it’s doing.

The first section is the diary/memoir of Emma Weil. She’s a lovely person to spend time with, direct, conflicted, an engineer. Her speciality is hydroponics and life-support. She’s aboard a mining spaceship in the asteroids when a mutiny breaks out—the mutineers are part of a planned revolution and their spaceship is part of a planned jury-rigged starship. They want her to go with them to the stars. She chooses instead to return to Mars and get involved with the revolution there.

Reading this section is such a joy that it doesn’t matter at all if you know what happens in it. This is also the most conventionally science fictional section—Emma’s an engineer, there’s a starship and a revolution, there are technical details about closed systems and they all have long life, you think you know what kind of book you’re getting into. You couldn’t be more wrong.

The second section is set in 2547 and is the memoir of Hjalmar Nederland, who is a Martian archaeologist literally digging up the remnants of his own life. (He knows he lived in the dome he is excavating, though he doesn’t remember it.) He finds Emma’s diary and it vindicates his theories. This whole section is both structured around and atmospherically charged by T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land. Robinson directly references it from time to time: “We fragment these ruins against our shore,” the unreal city of Alexandria, the vision of Emma as another climber. More than that, the spirit of the poem is the spirit of Nederland. He reads Cavafy, but he breathes Eliot. This is very hard to do, and even harder to do subtly, but Robinson manages it. It’s a strange dance of despair. Nederland knows that we can’t really know what happened in history, that we constantly revise and reimagine it, even our own history, even when we do remember it.

In this section we see Mars much more terraformed, but still caught in the strange political limbo. The Cold War is still going on on Earth, and Mars has the worst of both systems, the corporations squeezing and the five year plans. It’s interesting that they don’t have an internet and the Cold War has resolved itself in such a different way, when they have colonized the solar system and do have computers. I find this odder than older science fiction in some ways. This doesn’t make me ask where is my Martian terraforming project and thousand year lifespan. Perhaps because I first read it when it was shiny and new it still feels like the future, just one that’s subtly skewed.

When a huge circle of standing liths is found on the north pole of Pluto, Nederland realises that a hint in Emma’s journal explains that this amazing monument was left by the expedition she didn’t join.

At about this point in my re-read, I realised that it is my love for Icehenge that prevents me from warming to Robinson’s Red Mars. I like this version of long-life and forgetting and this version of slow-changing Mars so much better than his later reimagining of them that I felt put off and then bored. Maybe I should give them another chance.

The third section, set in 2610, involves a debunking of Nederland’s theory by Nederland’s great grandson, though Nederland is still alive on Mars and defending himself. And this is where Robinson provides the greatest meta-reading experience I’ve ever had. The whole thrust of this section makes me, the reader, want to defend the first part of the book from the charge of being a forgery. I love Emma Weil, I want her words to be real, I can’t believe they’re forged, that they’re not real—but of course, at the same time, I totally know they’re not real, Robinson wrote them, didn’t he? I know they’re not real and yet I passionately want to defend their reality within the frame of the story. I can’t think of a comparable whiplash aesthetic experience. And it happens to me every single time. Emma’s narrative must be authentically written by Emma and true—except that I already know it isn’t, so I know nothing and I feel… strange. It’s a fugue in text.

This is a book that asks questions and provides poetic experiences rather than a book that answers questions. It has a Gene Wolfe quote on the cover, and I’m not at all surprised that Gene Wolfe likes this. (I just wish T.S. Eliot could have lived to read it.) It’s odd but it’s also wonderful.

Jo Walton is a science fiction and fantasy writer. She’s published two poetry collections and nine novels, most recently Among Others, and if you liked this post you will like it. She reads a lot, and blogs about it here regularly. She comes from Wales but lives in Montreal where the food and books are more varied.

I’ll have to check this out.

I quiote enjoyed his Mars trilogy and was wondering if this tied into it at all (and I saw in your comments that it does not – LOL).

I did like Among Others, and I’d probably like Icehenge – but heavens, will there be a reissue in digital?

There must have been a printing error, giving you the right cover but the text of another book entirely. Icehenge is pretty much the worst published book I’ve read; indeed, this is the first book I’ve seen groups of people read just so they could share in its loathing. Those who finished it would then pass it on to others, saying, “You must read this. This is the worst book I have ever read.” I am distressed that Mr. Wolfe enjoyed it; but, then again, even Homer nods.

didn’t like the mars books and i didn’t like years of salt and rice, but i suppose i’ll have to give this one a try too.

I grabbed this as soon as it came out, both because I had really enjoyed The Wild Shore and because I had a personal connection to KSR (he had been my freshman writing instructor a few years earlier, so he was the first author I could say that I sort of knew). I was somewhat disappointed; I found it a little too self-consciously New Wave for my tastes at the time. I also didn’t really grasp the connections between the parts as well as I ought. Perhaps I should give it another go now that I am much older.

Another book that’s been sitting on my shelves un-re-read for a couple of decades.

I remember Icehenge because it was the first book where I encountered the idea of an unreliable narrator, or inconsistent narrators some of whom must be wrong (or maybe it was the first time I noticed…) In any case, I remember being surprised by the sudden transition from spaceship-to-the-stars story which I had been enjoying on its own terms, and then disconcerted by being told what I had just read was wrong.

I’ll pick it off the shelf and see how I respond to it now, and how well it holds up.

“To Leave a Mark”, the first part of Icehenge, was the first KSR story I read (on its original appearance in F&SF, and a lucky thing I saw it, because at that time in my life (1982) I was reading much less SF, and was only buying the odd issue of F&SF on the newsstand*), and I loved it. I never quite warmed (no pun intended) to the rest of the novel, though I did enjoy it. (The final part of the story, “On the North Pole of Pluto”, was also published separately, two years earlier even than “To Leave a Mark”, which suggests perhaps that KSR had the whole arc of the novel, with the veracity of the first part undermined by the third, planned from the beginning.)

(Actually, those titles for the separate sections are not used in the novel, just in their independent publication. And they were probably revised when included in the novel.)

I note that the French title is Les Menhirs de Glace (i.e. something like The Standing Stones of Ice), which seems literally fairly correct but not nearly as effective.

One other thing I like about Robinson, a triviality, is his affection for Wallace Stevens (my personal favorite poet), as signalled by such things as the use of The Planet on the Table, a Stevens quote, as the title of his first collection (I can think of one other SF writer (now more a mainstream writer) with a collection title derived from Stevens), and also by the use of a quote from a wonderful Stevens poem, “Tea at the Palaz of Hoon”, as the epigraph to the middle section of Icehenge.

I hope Tonstant Weeder never comes into contact with books like Jean Mark Gawron’s Algorithm, or Cecil Snyder III’s The Hawks of Arcturus, or … well, I could go on, but then there is really no accounting for taste, is there?

*(For whatever it may be worth, Kim Stanley Robinson is one of the writers I most credit for luring me back to the field, as it were, primarily with “Green Mars”, his best shorter work, and itself yet another treatment of immortality and forgetfulness, not strictly speaking in the same continuity as either Icehenge or the Mars trilogy.)

Ecbatan: Well I’m glad to hear you like it, I was starting to think I was alone here! (My thought with reference to Tonstant Weeder was that I hope they never even try Pale Fire.) As for the Stephens references, yes., isn’t that great!

Icehenge is pretty much the worst published book I’ve read

Clearly someone who has never read Pel Torro’s Galaxy 666 (Or Lee Corey’s Starship Through Space . Or Blish’s Spock Must Die! Or quite a lot of bad SF novels).

I hope Tonstant Weeder never comes into contact with books like Jean Mark Gawron’s Algorithm

SPEAK NOT THE NAME!

Heinlein’s Number of the Beast may have been the first book I chose not to finish but Algorithm is the first one I couldn’t finish. Although I still own my copy so in theory I could try again.

I did finish Algorithm, but only by slogging through the last third or so reading word by word, with no idea even what the sentences meant, let alone what was actually going on scene by scene.

The strange thing is, the rest of Gawron’s work ranges from OK to pretty darn good.