…or if it is, it’s also dark and troubling. Much like the present, really, only different. Only worse.

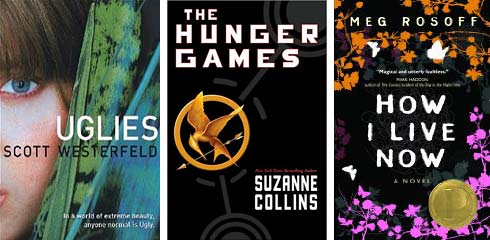

Such is the primary lesson of today’s exploding subgenre of dystopian young adult fiction. I hesitate to make too many assertions about which books started this undeniable trend, or which books are included, because there’s a certain squishiness to how the term itself is used these days. It’s sometimes used to describe books I’d class as post-apocalyptic (Meg Rosoff’s How I Live Now, Janni Simner’s Bones of Faerie and—just out—Faerie Winter). Others have observed that it’s become more or less the YA field’s code word for “science fiction,” not so different from how “paranormal” is regularly used to mean any contemporary fantasy with a romance. This is a valid point; YA does seem to avoid the term science fiction. (Though I wonder how that will morph as YA SF books with less of a focus on dystopian elements become more common. And I believe they will. Beth Revis’ Across the Universe being a prime example; for all that there are hallmarks of dystopia there—the controlled society, the loss of individualism—it is primarily a generation ship story.) At any rate, argument over the term’s use or not, there are a steadily growing number of YA books that are indisputably dystopian in nature, with the wild success of The Hunger Games having kicked the trend into high gear.

This makes perfect sense to me. Thinking back to my own high school years, I adored Farenheit 451, 1984, and Brave New World when we read them for class, and (not for class) Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale. So I’d hold that teenagers and dystopian works have always gone together. Over the past decade and the explosion of YA itself as a field, I believe the renaissance (or birth, however you want to look at it) of this subgenre being written for teens began with Scott Westerfeld’s Uglies trilogy. If anyone’s unfamiliar with these books, they follow the journey of Tally Youngblood in a future version of our world where at 16 everyone is made “pretty” and goes to live in New Pretty Town. Of course, they aren’t just making you pretty, and there’s an organized resistance movement, and the beautiful ruins of our own dead society. The books hit the nerve center of our culture’s obsession with looks over substance, while exploring the danger of conformity and a host of related issues.

In fact, many titles speak directly to historical strains of dystopian literature in SF. I relied on The Encylopedia of Science Fiction’s entry (written by Brian Stableford) as a primer. The entry talks about how “revolution against a dystopian regime” often turned into a plot with “an oppressive totalitarian state which maintains its dominance and stability by means of futuristic technology, but which is in the end toppled by newer technologies exploited by revolutionaries.” This seems to me to nearly describe Suzanne Collins’ The Hunger Games or Cory Doctorow’s Little Brother—although, in both those instances, it’s not so much new technology as the heroes effectively using the existing technology against the totalitarian regime. (Or, for Doctorow’s part, inventive new uses of that technology.) And, if Paolo Bacigalupi’s Ship Breaker doesn’t allow for any major overthrow of the society’s leaders, it is undoubtedly exploring a distorted landscape, environmentally and socially, a direct callback to another primary strain of dystopia. The Encyclopedia talks about post-WWII dystopian writing that has “lost its faith in the probability of a better future, and the dystopian image was established as an actual pattern of expectation rather than as a literary warning device.” The grim world of Ship Breaker seems to be clearly speculative from our current reality, though Paolo has said elsewhere that part of the reason the novel is more hopeful than his work for adults is because teens still have a chance to improve things. All of these dark futures come standard with philosophical and political themes; all of them believe in the possibility for change.

At the end of Laura Miller’s New Yorker essay about YA dystopians, she wondered if the anxieties showcased in most of the books aimed at teens are truer reflections of the ones their authors feel. While this may be a factor, I think most—the best—YA writers are tapped into what it feels like to be a teenager (something that really doesn’t change that much from decade to decade). So I suspect the core reason these books connect so well with teens—many of them even with the potential to be that holy grail of YA, appealing to girls and to boys—is that most of them are, at heart, about pulling apart the oppressive assumption and the unexplained authority, and then rebelling against it. Tearing it apart. In a world where choosing what to rebel against seems impossible for every generation (“What do you got?”), stories set in worlds where the decision is easy and justified will never lose their appeal.

There’s this popular view of teenagers as intellectually lazy (because they text or something? I don’t know) and politically uninvolved. I’d argue that the popularity of dystopians exposes the lie beneath both these, well, lies. These novels may spring from the anxieties of older people, but they are cultural anxieties—and teens are also members of our culture. The beauty of well-aimed dystopia for teens is that it can potentially have a direct effect on what it’s arguing against, by speaking directly to the people best suited to alter the future. Maybe things don’t look so bleak after all.

Gwenda Bond writes YA fantasy, among other things, and can be found at her blog and on Twitter.

Hmmm… so maybe there is hope for our future? Now, if only we could get everyone to actually read a whole book :-)

Teens in my experience read more whole books than anyone I know. Which is also a hopeful thing. :-)

Anyone reading more is a good thing!

Oh, and thanks for pointing out Faerie Winter, I had no idea this was on the horizon. I’ve added it to my TBR list.

Terri Windling and I have a YA anthology of dystopioan stories coming out in 2012. It’s called AFTER, and each story takes place after some cataclysmic event where everything changes. We emphasized that we wanted stories with an energy and verve to counteract the possibly depressing circumstances of the characters.So far, we’ve gotten a magnificent variety.

The anthology was a harder sell than novels as we believe that a whole book of many dystopic stories could be too depressing. We think we’ve avoided that.

love this article. LOVE.

if you look at what the adolescent brain is going through developementally, it totally makes sense that dystopians are where it’s at. the ability to imagine what someone else is really feeling and why someone else might be doing something are fresh concepts in middle grades. and then later, the grand scale of “where do i fit in with all of this crazy biz” cognitive development stage is reached.

while the personal preference of the reader, pop culture, and the media are obviously huge factors, the brain science is something to consider as well. they know what they like to read and there are amazing authors out there giving them the opportunity to take a literary journey through another world while examining their own existence.

reading is just so awesome. and so are teeanagers, quite frankly.

Thanks, everyone, for the comments.

Ellen — Very much looking forward to the dystopian anthology. While there are lots of great sweeping trilogies in this area, I think dystopian concepts can work just as well in a self-contained way (because they’re so concentrated).

Great article, Gwenda! I’ve been a fan of dystopian literature since I was a teen (and The Handmaid’s Tale had a big impact on me when I was younger). I’m glad to see dystopia’s new popularity in YA, although it does irk me that the term seems to be increasingly misused to describe books that don’t fit the definition. In particular, many people don’t seem to understand the difference between dystopian and post-apocalyptic.

I agree that the teens I know read more than anyone I know, and are definitely not intellectually lazy. Most of them care passionately about the things going on in the world and have strong opinions about politics, society, and the like. While I don’t always agree with their opinions, I admire the passion and depth of thought behind them.

Great, thoughtful article. I’m going to print this out and keep it.

Great post and reference links, Gwenda. Thank you for putting real substance behind what many consider merely a stubborn fad in the YA market. The best dystopians are out there to ignite inspiration and to allow readers of all ages to revel in the wondrous “What if…”

To be fair SheilaRuth, many post-apocalyptic societies are dystopian.

Please don’t forget about Feed, by MT Anderson, written 3 years before Uglies and an absolutely brilliant, subtle YA dystopia!!

One interesting thing about Feed is that it’s apocalyptic, rather than post-apocalyptic — but no one’s really paying attention to the ongoing collapse of the world. It’s also a much more direct critique of contemporary society.