Each Tuesday, in honor of The Center for Fiction‘s Big Read of Ursula K. Le Guin’s classic Wizard of Earthsea series, we’re posting a Jo Walton article examining the books in the series.

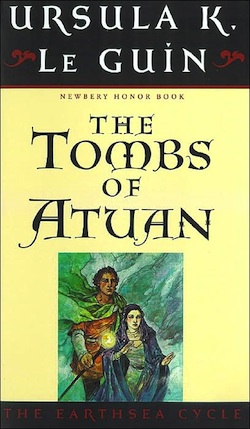

Le Guin has said of the first three Earthsea books (in The Languages of the Night) that they concern male coming of age, female coming of age, and death. Presumably it was the realisation that most lives contain other things in between that prompted her to write the later books. The Tombs of Atuan has long been a favourite of mine but reading it this time I kept contrasting the male and female coming of age in the two books.

The Tombs of Atuan is about a girl who is the reincarnated One Priestess of the Nameless Powers. She lives on the Kargish island of Atuan in the Place of the Tombs, and is mistress of the Undertomb and the Labyrinth. She dances the dances of the dark of the moon before the empty throne, and she negotiates a difficult path with the other priestesses, who are adult, and adept with the ways of power. It is a world of women and girls and eunuchs and dark magic, set in a desert. A great deal of the book is set underground, and the map at the front is of the Labyrinth. It couldn’t be more different from the sea and islands of A Wizard of Earthsea.

Again, I may be too close to this book to see it clearly. When I was a child I used to play the sacrifice of Arha, putting her head on the block and a sword coming down, to be stopped at the last minute, while the priestesses chanted “She is eaten.” Sometimes I’d be Arha and sometimes I’d be everyone else, but it never failed to give me a thrill. I’m not sure what it was in this dark scene that made me re-enact it over and over, but it clearly didn’t do me any harm. It was also my first encounter with the concept of reincarnation.

We’re told at the end of A Wizard of Earthsea that this story is part of the Deed of Ged, and that one of his great adventures is how he brought back the Ring of Erreth-Akbe from the Tombs of Atuan. But the story it isn’t told from his point of view but always from Tenar’s, Arha’s, the One Priestess. She’s confident in some things and uncertain in others, she has lost her true name. I’ve always liked the way he gives her name back, and her escape, and the way she and Ged rescue each other.

What I noticed this time was how important it seemed that she was beautiful, when really that shouldn’t have mattered at all, but yet it kept being repeated over and over. Also, A Wizard of Earthsea covers Ged’s life from ten to nineteen, and at the end of the book Ged is a man in full power, having accepted his shadow he is free in the world. The text at the end describes him as a “young wizard.” The Tombs of Atuan covers Tenar’s life from five to fifteen. At the end, when she gets to Havnor with the Ring on her arm, she is described as “like a child coming home.” Tenar is constantly seen in images of childhood, and Ged in images of power. If this is female coming of age, it’s coming out of darkness into light, but not to anything. Le Guin does see this even in 1971—a lesser writer would have finished the book with the earthquake that destroys the Place and the triumphant escape. The final chapters covering their escape through the mountains and Tenar’s questioning the possibilities of what she can be do a lot to ground it.

This is also beautifully written, but it isn’t told like a legend. We are straightforwardly right behind Tenar’s shoulder the entire time. If we know it’s part of a legend, it’s because we’ve read the first book. There’s none of the expectation of a reader within the world, though she never looks outside it. Earthsea itself is as solid and well rooted as ever—we saw the Terranon in the first volume, here we have the Powers of the tombs, dark powers specific to places on islands, contrasted to the bright dragons flying above the West Reach and the magic of naming.

Jo Walton is a science fiction and fantasy writer. She’s published two poetry collections and nine novels, most recently Among Others, and if you liked this post you will like it. She reads a lot, and blogs about it here regularly. She comes from Wales but lives in Montreal where the food and books are more varied.

The images painted on the wall of one of the chambers off the labrynth – human figures with the wings of birds, but flightless and condemned to live on dust – always stayed with me, partly because it seemed so familiar when I first read it. Much later I found that it came from the Sumerian tale of Ut-Napishtim and described the fate of souls in the house of the dead.

This was the first of the series I read, at 12 or so, and it colored the way I read the other volumes later- for one, I saw the rest of the Archipelago, especially Gont, as all pirates. And even then, I was annoyed at the interloper Ged, who dropped her off when he was done with her and went on to do more wizard stuff.

I feel that LeGuin wanted to revisit abandoning her when she wrote Tehanu, but- well ….

The Earthsea trilogy never did much for me (I read it for the first time 4 years ago, at age 29) but for some reason I really enjoyed this book. The underground labyrinth cult recalls one of Howard’s Conan stories that I didn’t read until later.

Very good point about Tehanu not having anything to move towards. IIRC, all she’d shown was enough decency to rescue Ged, but everything she’d learned from her religion was a waste.

I do think it’s unusual– and maybe valuable– to have a fantasy story about what it’s like to be inside a decadent cult, to teach the idea that some old and elaborate systems aren’t doing any good, but look very normal from the inside.

Has anyone checked out “The word of Unbinding”? This was the short story in the collection The Winds Twleve Quarters. In the short preface before it Le Guin states that this is what lead her to write the Earth Sea Trilogy. That story too was what got me to read the trilogy and the subsequant novels after.

For what it’s worth, the image of a child being eaten (by suffering or fears) occurs in two relatively modern poets that I know of:

Janet Frame

and

Alasdair Campbell

In Janet Frame’s poem, she herself is the one eaten by her experiences (IIRC), while in Alasdair Campbell’s, it is his daughter eaten by the fears of the night.

I don’t know of anyone else who uses or has used that image, besides Ursula Le Guin.

@5 Lapbplayr

The Wind’s Twelve Quarters is a favorite of mine. It was her Earthsea short stories in there that sparked my re-read of the trilogy.

What I always liked about this book, and the next, to a lesser extent, was that it was not told from Ged’s point of view. After the first book, I feel like too much time inside Ged’s head would weaken the story. Seeing his acts from the outside helped to preserve his legendary quality for me.

“When I was a child I used to play the sacrifice of Arha, putting her head on the block and a sword coming down, to be stopped at the last minute, while the priestesses chanted “She is eaten.”

Oh! I did this too! I found this book absolutely compelling. I loved the fact that Arha was so – well, surly is he word that comes to mind. She is so serious and intense, and cruel at times, and that seemed very powerful to me. Few other heroines seem so real to me, or so like myself!

I loved the fact that Get was in her power, and the way he reacted to that situation, I found that relationship very believable. But I never liked the ending, where she seems so diminished. Her world becomes larger and she much smaller.

I wonder why that sacrifice fascinated me so much, it seems to touch on something very true and deep.

Quarmall is all…….

I really enjoyed your perspective. Some of your points of dissatisfaction are also present in the Theseus myth. Ariadne helps him through the labyrinth to destroy the Minotaur but he later abandons her on an island on his way home.

As far as beauty and chastity playing a part for no reason, the whole reason for the Minotaur was because they refused to sacrifice a beautiful white bull and instead gave a substitute or lesser sacrifice. Poseidon was insulted by the slight and cursed the king. Then the Athenians were obliged to pay a tribute of beautiful virgin boys and beautiful virgin girls to placate the Minotaur. Theseus a prince decided to volunteer as tribute to hunt the Minotaur. Ariadne is a princess and Theseus as prince the expectation would be for them to marry.

I think this is a retelling of that story but not from the perspective of the Minotaur which has been done but from the perspective of Ariadne which hasn’t.