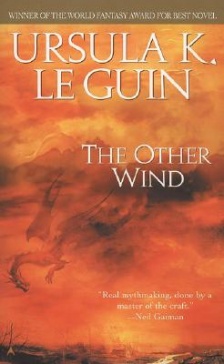

Each Tuesday, in honor of The Center for Fiction‘s Big Read of Ursula K. Le Guin’s classic Wizard of Earthsea series in October, we’re posting a Jo Walton article examining the books in the series. Click the above link for more coverage.

My problem with this book is how much I like the first trilogy, and how much The Other Wind needs to undermine them to make its point. Probably if I had read all these books in the same week, whether in 1974 or in 2002, I wouldn’t have this particular problem. This problem comes from reading the first books over and over between 1974 and 2002 and seeing my own things in the margins, so that when Le Guin gives me different margins I turn into the Winds from Ventus and disbelieve. This is only my second reading of this book, which I read immediately it was published and haven’t picked up since. I cannot like it.

Spoilers.

Let’s start with my personal problems. I mentioned in my post on The Farthest Shore that it had helped me cope with death in real life. This is why the idea of revising death in Earthsea and is very difficult for me to deal with. Also, I had worked out my own way of reconciling the reincarnation of The Tombs of Atuan and the dark place behind the wall, which was to think that people went behind the wall and then on from there to rebirth. So the problem The Other Wind is dealing with looked to me like a platypus—a non-problem created by looking at things the wrong way.

Setting that aside, but still on the subject of death in Earthsea, there’s something else problematic. It turns out in The Other Wind that it’s the Kargs who have been right all along. So this manages to combine the meme of “over-sophisticated civilized people should have listened to the the unsophisticated savages who were close to nature” with “the white people were right all along”. I have always liked the white people being the savages—I liked it when I was a child and I like it now; it’s a reversal worth doing. But if they were right about how to live all along, that undermines that. It’s a reversal of a reversal.

I also have a problem with the dragons in this book. Again, this is probably largely caused by the twenty-year gap in my appreciation of Earthsea. Like Arren, I felt everything was worthwhile because I had seen dragons rising on the wind. Now I’m supposed to believe some very difficult things about dragons that don’t much seem to fit with my understanding of them. My first reaction to The Other Wind was that Le Guin didn’t understand her own dragons anymore.

Apart from the issues of death and dragons, this strikes me as a flawed book. The shape is strange. We begin by following Alder to Gont to find Ged, and it seems as if it will be a book about Alder and his problem. He leaves Ged on Gont and goes to Havnor, and once he gets to Havnor the book almost forgets him, he is secondary to a story focused on Tenar and the king Lebannen. The bits I like most are about Lebannen and the princess from Hur-at-Hur, where the book seems to warm up a little. It ends on Roke with uncomfortable redefinitions of death and dragons.

Ged doesn’t feel like himself. Tenar feels as she did in Tehanu, which isn’t as she did in The Tombs of Atuan, but I’ll take it. I was interested in Alder, but I felt the narrative wasn’t.

The whole thing feels tentative and questioning as if the cloud-capped towers could melt away to air at any moment. The worst thing about this second trilogy is that they do reflect back on the first three, I can no longer read the early books without the shadows of the later ones falling back onto them. I’m so glad Le Guin has gone on to make new worlds, ones where she can be confident again.

Jo Walton is a science fiction and fantasy writer. She’s published two poetry collections and nine novels, most recently Among Others, and if you liked this post you will like it. She reads a lot, and blogs about it here regularly. She comes from Wales but lives in Montreal where the food and books are more varied.

The stuff with Ged talking to Alder is wonderful. The resolution… isn’t.

The line about “you can’t make poetry about tariffs and shipping taxes” is pretty good, but then I remembered that Kipling had already falsified it (Our Lady of the Snows)

I had similar problems to you, but I am glad this book exists if only for

“O my joy, be free…”

To now take a different view, if LeGuin *didn’t* think that the dead beyond the wall went on to be reborn, it meant that everybody (except the Kargs) went to hell when they died. That is, continued existence without light, without love or friendship, without the possibility of meaningful action, forever. It doesn’t bear thinking about.

Thanks for the thoughtful review. I am a bit torn about reading this now, since the original trilogy means a lot to me also. But I have to say that I am intrigued by the reversals, and I wonder how this work will affect my own reading of the past stories.

a) great piece

b) but you should somehow explain how this book fits in with the first earthsea trilogy somewhere in that first paragraph. I only figured it out in paragraph 2, sorta. If people havn’t read the first trilogy its not obvious that they are related. (and I loved the original so much in the late 70s that I’m excited to find this new bit I hadn’t heard of even if it makes me sad).

c)Sometimes authors do things so strange that they’ve obviously had a change of heart somewhere along the line. Like Sterling in “Zenith Angle” when 9/11 obviously scared him and he got all “the govenment should have a back-door to EVERYTHING!”. Fear/loss/life does weird stuff to people.

I was somewhat bothered by the afterlife we saw in the original books even as a child, and more so as an adult; I didn’t think about the possibility that people went on from there to be reincarnated because I assumed the Kargs were wrong. (We actually do see some evidence that they are wrong, in that souls are summoned several times in the original books. Of course those particular people might not have been reincarnated.)

So, it was something I wouldn’t have minded seeing changed. But I didn’t care for the way it was changed, for all the reasons given here, and more besides; it’s been some time since I read this book but I seem to recall intimations that the suppressed Pelnish lore was more correct than the standard magic, so what does that make of The Farthest Shore?

In particular, large chunks of The Farthest Shore now make no sense, if indeed the afterlife as we have it is a gigantic mistake instead of the natural counterpart to life.

The Pelnish lore allowed one to do certain things more effectively than the lore of Roke, but it is not at all clear that they were wise things to do.

Sunjah: The joyless afterlife beyond the wall isn’t all that far removed from the classical ideas of the afterlife — Achilles, summoned in The Odyssey says it’s better to be a slave on earth. One of the reasons Christianity became so very popular in the first centuries of its existence is because the possibility of a heaven was a big incentive to people who had lived with belief in only a hell.

I read all of the books first as an adult, and i love all of them as telling different truths about the same world. I’m sure it is to do with not being particularly attached to the Earthsea of the original trilogy, so the later books don’t feel disruptive or like betrayals of anything i took as sacred. The Other Wind is among my favorites.

I agree with you that the story itself feels disjointed in some ways. And i see what you’re saying about the disappointing “the white people were right all along” angle — but maybe it’s not so much that the Kargs were “right” as that different folks remembered (and mis-remembered, and played “telephone” with) different parts of the truth, and the Kargs had one piece. (The wizards weren’t necessarily “wrong” either, they’d just forgotten the full terms of their power.) Healing is a main theme of the book so it makes sense to me that this should also cross enemy lines. That doesn’t, i think, negate the significance of the near-revolutionary facts of race in Earthsea, i think it makes the whole world richer and more complex.

The first books seem to give evidence that there was no re-incarnation. If there were, how could you call up the spirits of the long dead?

I wasn’t clear about the part where the construction of this grim afterlife was supposed to enable magic. Did I read that right?

I was quite satisfied with the view of the afterlife in the first trilogy, grim and disagreeable as it was, because it reminded me of Sumerian myths and so it had a very ancient feel to it. There, apparently it was the Underworld for you or becoming a god of sorts (the Greeks had a similar concept; only a very few heroes, most of them descended from proper Olympian gods, made it to the Elysian Fields or the Olympus… everyone else went to Hades and it wasn’t a nice place) and in the Underworld they ate dust and existed in perpetual darkness. Very much like that place behind the wall.

I liked “The Other Wind” right up to the very end. It lost me there. I felt it stepped outside the context of the novel and made a religious/philosophical statement applicable to our world and I don’t like that sort of thing. But maybe I just read too much into it…

I had thought that the point of The Farthest Shore was that the joyless spirits beyond the wall were not the whole selves of the dead, but mere names; their life lived on in the whole of creation. (Though that also conflicts with reincarnation.)

I agree with those who thought that the Kargs were wrong. In addition to what others have said, there’s something very odd about Arha’s soul being reborn again when she dies, because Arha isn’t meant to have a soul – she has been eaten.

Another Andrew: It doesn’t conflict with either Norse or Egyptian reincarnation, where you have more than one soul. One soul, your continuing life, goes on to rebirth, and one, your memories of the specific life, stays in the underworld wandering blindly unless summoned, while the traditional third remains in your legacy in life.

I think the idea with Arha was that one of her souls was eaten to make room for one of the souls of her predecessor(s) to come into her body. But none of this fits at all with the explanations in The Other Wind.

I’m relieved to see Jo’s opinion of the later Earthsea books — I have wondered if it was just a guy thing that I didn’t like them.

I like the second set of books just fine–but then I wasn’t particularly enamored of the first three books when I read them as a sprout in the very early 1980s. Liked ’em fine, but didn’t really reread them again.

There’s clearly an early adopter/late adopter distinction going on here.

I don’t think it’s clear in The Tombs of Atuan whether Arha is really reincarnated (in any sense) or if the Kargs just think so. Unless I am forgetting something (always a possibility), she never actually remembers anything from her previous life – everything she should know (e.g., the Labyrinth directions) is told to her by one of the older priestesses. (Which doesn’t prove that she isn’t reincarnated, of course.)

Huh. Jo, we both read and loved the original Earthsea books when we were children, but now that we’re adults, we seem seem to have an exact opposite reaction to the early vs later Earthsea books: you like the originals and dislike the later books, whereas every time I go back to the originals as an adult, I find them dissatisfying – the approach to gender and the approach to class both rub me the wrong way.

The later three books feel, to me, like Le Guin is finally getting the portrayal of her world *right*, looking at the places of women and men, and looking at the lives of ordinary people as well as at nobles and wizards. That she decided to retcon Earthsea’s spiritual cosmology in The Other Wind is, to me, just icing on the cake, as I never really enjoyed the portrayal of the afterlife in the original books.

Speaking only for myself –

The approach to gender and class in the originals may not be all that palatable, but I simply can’t swallow the later books as being set in the same world as the originals. Roke and (probably) wizardry wouldn’t have been able to exist under the ‘new’ rules.

I think if she’d tried to write the ‘corrections’, the later books as a secret history, working in stuff in the corners, there way Tim Powers does with real history, it may have been possible to pull off. But she didn’t. Instead, she undercuts, and contradicts, and I put the original presentation up against the later, and they can’t exist together.

Sequeying to something that’s bothered me for years …

I also don’t see how Ged completely lost his magic. It’s like losing the ability to carry a tune, or match colors.

Elaine Thom: Ged lost his magic ability closing the gap in the world of death. It’s like somebody singing a note so high it cracks their vocal cords so they can never sing again, or someone seeing a light so bright they become blind. It’s the price he pays for defeating Cob. I don’t like it, but it’s strongly implied in The Farthest Shore and doesn’t pull the wrong way the way so much in the later books does for me.

Once upon a time Ged losing magic didn’t bother me. Somewhere, though, it started to. It seemed that it ought to still sort of be there, and maybe he couldn’t do everything he used to do, he’d still have a bit of it.

My biggest problem with The Other Wind was that I had read it right after reading The Amber Spyglass, and I thought that Philip Pullman had looked at a similar setup in what was for me a more satisfying way than the way death was revisited in The Other Wind.

My second-biggest problem was that I liked the world of the first three books a great deal, and the world of the later three (Tehanu, Tales from Earthsea, and The Other Wind) is a different world stylistically, one I don’t like so well.

So I’m glad to know that at least one other smart well-read person didn’t love these books, whether their reasons are the same or different from mine.

I’m glad to read these reviews of the latter 3 Earthsea books. I really disliked Tehanu, and disliked the last two only slightly less. I’m extremely sympathetic to what Le Guin was trying to do – the gender politics of the original trilogy were screwy, and trying to re-envision one’s own work like that is an interesting project. But as you write the execution is bad – Tehanu does not actually convey any empowering message, and the attempted re-interpretation of Earthsea’s history in Dragonfly and The Other Wind fails completely at believability. Without any indication that the narrator of the first trilogy was unreliable regarding facts, we just have characters and institutions behaving in totally inconsistent ways.

I quite liked Earthsea to have dragons and magic in it, and found the loss of them a bad trade even if it liberated souls from hell. Of course, I don’t have to live there, or more to the point die there. But still.

The book also felt… dishonest? to me. Revisionist. Like you, I can’t believe in it.

In the first series and the first two thirds of Tehanu le Guin constructed a very solid Bronze Age world. Like many Bronze Age societies it’s horribly sexist, people live in abject poverty, governance is uneven and the afterlife is crappy.

But the cure for most of those ills is time, not the unbuilding of walls. It felt like le Guin was trying to superimpose modern values onto a culture where they had no organic roots, and didn’t fit. And because the earlier books were better constructed it that vision of Earthsea I believe, not the one you see through the fan if you hold it up to the light.

I felt that the Kargad lands based their rule upon deliberate lies- reincarnation was just an unprovable/ undisprovable lie to perpetuate the priestesses power, the Priest-kings became the Godkings- so I didn’t worry about whether they were “right” or not.

I don’t know what this book did to the above discussed issues. I read Tehanu years after the original trilogy, and strongly disliked important parts of it enough to not read ant subsequent works in the series. I have been reading Jo Walton’s posts to decide whether I should continue, and I don’t think I will.

This is certainly a problematic book for me, as any mucking about with the underpinnings of a successful earlier series must be, but I can’t dislike it as much as Jo does. Perhaps that’s because I read The Original Trilogy (TOT?) as an adult, or perhaps because I would gladly wash Le Guin’s feet with my beard and therefore may be somewhat unable to rip on it too badly. But I do really like a number ofthe writing bits, including the developing relationship between Lebannen and the Karg Princess (as did Jo), the character of Alder, even the kitten. I love the mature wisdom of Tenar here (perhaps a bit like a certain Portland-based writer?), and, unlike Jo, I find Ged convincing. The Ged of this book is a man who has had the time he needs to reconcile himself to the loss of his Power, which was new and raw in Tehanu; he has found a new place for himself and happiness there, and I believe in it.

Jo, I can’t think of any textual evidence from TOT for your idea of the Dry Land as a kind of temporary purgatory. There’s a moment where she says “the dead are many, but that land is large,” which I suppose is ambiguous, but remember that Cob was able to recall Erreth-Akbe, dead for centuries.

Going deeper: The end of the book certainly overturns some aspects of the metaphysics of TOT, but I think it actually fits rather well with parts of its thematics. Look at what the Rune Makers did: they sought/promised an immortal, joyful life, but in the act of creating it instead condemned the people of the West to an Eternity of empty existence, neither life nor rebirth. (The description of that moment is honestly one of the more chilling things I’ve read). To me, that’s a writ-large version of what Cob was attempting with his vision of individual immortality. The flaw in the thinking, the surrender to the shadow of one’s own death, is the same in each case, and the result is always ruin. Ged frees Cob’s victims, and Cob himself, by what was then understood as an unshackling from an artificial tie to the living world; at the climax of The Other Wind, all of the dead are freed to rejoin the broader universe from whence they came. It undoes some of the specifics, but not the philosophy, for me at least.

But: Some dragons are people, some people are dragons: yeah, that never worked for me either.

For those who haven’t read it, I’d say that it’s worth reading just because one should never turn down a chance at Le Guin’s prose, and it is thought-provoking in spots. But if you truly deeply hate revisions and retcons, even at the philosophical level, it might not be your particular cup of tea.

Thanks for a stimulating essay Jo,

S

My problem with the second trilogy is that the friendship/partnership of Ged and Lebannen is so hugely important in Farthest Shore – dude, they go *into and out of death together* – that it breaks my heart that LeGuin decided to estrange them and never heal it in the second trilogy. If she really dealt with that in Other Wind, it would be tragic but powerful, but instead it just sort of falls out of the story.

I think that some books one reads at a young and impressionable age take on the form almost of mythology, especially for people who don’t have an religious upbringing and don’t get a taste of mythology that way. The first trilogy of the Earthsea books and The Lord of the Rings worked that way for me, anyway. Maybe that’s why there’s such a passionate response to the second trilogy — the books are so different they seem almost like heresy. I love Tehanu, as I said, but I deal with my dislike of the other two by not rereading them, by pretending they don’t exist.

What Silvertip said.

In Tehanu, I enjoyed Ogion’s story about the old dragon-woman and the implication that Tehanu is of this nature. I find the dragon-human lineage intriguing and was hoping it would be explored later (without Tehanu‘s ubiquitous themes of misandry).

Tehanu did not taint the orignal Earthsea trilogy for me, but certainly did not enhance it much. There was no plot and no advancement of the series. So I am eager for another novel! Thought I’d seek out The Other Wind and see where it takes me.

Thanks to your revealing article, I will NOT be reading The Other Wind, an ill wind it must be! I suspect it is even worse than Tehanu (which had its moments). The Earthsea trilogy is a beautiful thing and I do not wish to spoil it.

Thanks for the warning!

I loved the original trilogy–Wizard especially with its Taoist wisdom was helpful to me as a teenager–but I got to see Le Guin when The Other Wind came out. She came to Berkeley on the promotion tour. What I remember is that she started writing beyond The Farthest Shore because she was bothered by the idea that only men can do magic, and that women’s magic is bad magic. So she wrote as exploration. Okay. Then I read all six books, the first four again, then the short story collection, then The Other Wind. Ah. So satisfying, when seen that way. With that said, I haven’t read them in a few years. I remember being satisfied with each, but appreciating Wind as the product of an older woman who had lived a thoughtful, creative life.

I loved the first trilogy – read it many times, first as a kid – and yet consider The Other Wind an excellent book which is in no way inconsistent with the previous works. It enriches them. As for the alleged inconsistencies/contradictions, some of them have already been dealt with in some of the previous comments I do not have much time so let me just mention these:

1. None of the books says that Arha’s soul was eaten – we are just presented with what some inhabitants of that world say and/or believe.

2. Earthsea is not our Bronze Age world which means there may be huge differences between the two. Earthsea is just Earthsea.

3. There is no difference between how sexes are portrayed in all the books. The only difference there is may be caused by presenting the world as is seen from different perspectives – obviously the world, women and men are viewed differently by Ged the boy and Ged the old man… not to mention Tenar the old woman. NB all women presented in the last novel are far from ordinary / common – they are all powerful / influential and as such could not be used to prove that the dynamic of sexes changed between the books… Which it did not as we had powerful / influential female characters in the first trilogy as well.

Thanks a lot for your review. I much appreciate its personal tone. This is what makes the internet worth its while :-)

Personally, I love all of the books. Also the last 2 novels. And the collection of short stories is ok.

For me, the first trilogy is a work of youth. I appreciated it when I was a young man. The whole “wise hero thing” suited my young years, where I believe heroism is a suitable theme. I will admit, that when I read Tehanu as a young man, I was very dissapointed; it was all abut mundane and everyday stuff and nearly all the hero-wizard-dragon-stuff was gone. But today, nearing 50, I appreciate the Le Guin’s fine character portraits and filosophical and political topics, which mixes with a bit of wizard-and-dragon stuff. Very satisfying and VERY rare (almost all fantasy is suited only to teenagers, in my opinion). I stille wrestle with the whole “dragon” – “other wind” – “reversal of death” – “once men and dragons were one” -stuff; what does it mean and do I agree? But again; how often do we get to wonder about such things in fantasy-books? Personally, I only know of one other fantasy-epics that does it (I probably don’t need to mention which).

Read all 6 books in succession over the last few weeks and was thrilled with all of them.. Funny enough the only time I sped read through any of them was in “the other wind” the boat ride from Havnor to Roke with the king and all the other main characters sort of dragged on a bit. Thinking back on it I might have skimmed through a few pages in the 5th book dealing with the history of earth sea; finding that it was a bit repetitive if one recalled facts from previous books in the series.

I have read many comments asking about the human/dragon relationship and finding difficulty with it. If anyone may re-call a Jim Henson film called the “Dark Crystal”. In the film there was a similar scenario where a great being had been split into two. Although different… And forgive me I cant re-call what they were called or even much more about the plot of that film. I remembered a few scenes from the film and used it as a reference when trying to wrap my head around the dragons and humans were once one being scenario.

I think metaphysically the dragons in Ursula’s novels represent imagination, magic, life source, raw power in it’s purest form, angels even (if you’d like to go that far and all the implications that go along with it). Basically physical embodiments of all that is mystical in the world of earthsea. An being the authors world she was free to do what she pleased with them. Surely some people have more of that raw energy in them than others. Some people are just born with a desire to be free, others are more bound to worldly desires or find joy in simple things. With her hero’s in the novels she explores these themes and celebrates them…

On a final comment , like so many others, I too wished in the last book by some twist of fate we might see Ged returned to his former glory and yet again be a hero. Sadly I think that would go against the writers overall theme. Although in the last paragraph we have Ged and Tenar speaking. The last thing Tenar sais to Ged is: Have you walked in the forest yet ? I dont know about anyone else but I was immediately reminded of Ged’s old master “Aihal” being a wanderer of the forest and thought: just maybe as the rift between earthsea had been mended, perhaps Ged’s magic had returned.. Just a hopeful thought and a good ending to a masterfully written series.