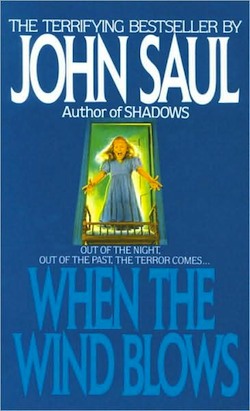

Even by the standards of the horror section, John Saul always had the most lurid covers in the bookstores of yore. His were the novels that tended to line the bottom shelf, presenting image upon image of innocent-looking kids in creepy gothic settings. Often they were blonde girls in nighties, with scary demon eyes.

Beyond those covers, I dimly remembered, was plain-Jane prose, simply drawn characters and a whole lot of kid death.

This impression, it turned out, was pretty much on the money, at least as far as 1981’s When the Wind Blows is concerned. The novel is the story of a one-horse town in Colorado, Amberton, a place built by coal and its profits. At first the community thrived and the mine owner, Amos Amber, raked in money by the handful. He and his wife, Edna built up a fortune and got accustomed to looking down their noses at their hardworking labor pool. But as long as people were, in fact, employed, everything was reasonably harmonious.

A tragic wobble in this delicate balance developed in 1910, though, when blasting operations at the mine disturbed a cave the local aboriginal tribe had been using, since time immemorial, as a graveyard for their stillborn infants. The blasting roused the stillborns’ wrathful spirits—the neverborn hate having their naps interrupted! To return the favor, they flooded the mine. Amos died, along with a full shift of workers.

Fortunately for Edna, the money Amos had already amassed was more than enough to sustain her sumptuous lifestyle. Less fortunately for Amberton, she had no sense of noblesse oblige. Edna was angry, in any case, to be left widowed and with a newborn. So she shut the mine down, leaving Amberton to wither without its primary employer and kept herself busy by tormenting the daughter she’d borne just as Amos was drowning.

For fifty years, the ghosts slept fitfully. Now and then, people would hear the infants of the cave crying when the wind blew. (Most of them put it off to hunger-induced hallucinations, I’m sure.)

When the townsfolk hit upon the idea of sprucing up Amberton and reinventing the place as a tourist destination, Edna—a control freak if ever there was one—starts flirting with reopening the mine. Nobody in old Amos’s town is going to have a real paycheque unless they have her to thank, seems to be the rationale. The water babies, as they’re sometimes called, beg to differ: they lure her mine engineer to a grisly death. And that’s when it all really falls apart for Edna, because her downtrodden daughter Diana insists on adopting the engineer’s orphaned child, Christie. Soon she’s got a nine-year-old underfoot, her meek middle-aged daughter is defying her at every turn, children are turning up dead in and around the mine, and the townspeople, who have had all the time in the world to build up resentment towards their former corporate masters, are getting ready to dish out some serious blame.

Saul’s particular brand of horror draws its power from juxtaposing childhood’s innocence with murderous evil. A few children are legitimately corrupted in his works, but more often they are the pure-hearted victims of other wickedness: ghosts, possession, unkindness, terrible accidents, and physical and emotional abuse by adults.

Unfortunately, a potential powerful concept is about all When the Wind Blows has going for it. I had remembered Saul’s books as quick, scary reads, but the plotting, prose and characterization in this novel are really poor. Diana and Edna are all but directionless, whipsawing from mood to mood and plot point to plot point in a way that comes off as entirely random. The class dynamics and rising anger of the town never really live up to their promise, and by the end of the book it’s apparent that nobody can really put the water babies to rest… they’re just going to simmer on forever, unable or unwilling to go back to sleep, and killing whoever shows up.

In the end what surprised me about When the Wind Blows wasn’t that it disappointed—it was how deep the disappointment went. I had hoped, for my own reasons, to find Saul a better writer than I remembered, or—that failing—not much worse. Instead, I found a book so poorly crafted that I’d rather like to bury it in a nice deep ghost-free mineshaft.

A.M. Dellamonica has a short story up here on Tor.com—an urban fantasy about a baby werewolf, “The Cage” which made the Locus Recommended Reading List for 2010.

I read this book with that same thinking you had in mind. I wanted to see if Saul lived up to what I remembered from years back. Funny that we chose the same book for it too.

I chocked my dislike of this book up to just being a bad book. But now I’m wondering if it’s my memory that’s the bad piece here. Perhaps I should reread a book I enjoyed back and the day and see if it still holds up now? Who knows?

When I was a tween (not that the word ‘tween’ existed back then), John Saul was one of the first non-King, non-Koontz writers I ever tried to read. I read a couple of them and then asked my dad if he’d ever read them; when he said he did, I offered him some of my newer releases and he shook his head and said, “They’re all the same, they’re all just about kids dying.” I was shocked at first (my developing reader’s mind hadn’t really noticed that) but then I realized he was pretty much right.

Kinda took the wind out of the rest of his books I tried tor ead.

Greybon, if you try that experiment I’d be interested to hear the result.

Jack, I think the books work better for younger readers because they are about kids dying–it makes the horror more tangible.

I remember liking Shadows, which involved a scary boarding school and computers powered by brains in jars, if I remember right. I don’t know if I should go back 20 years to find out if I was wrong.

I rmember reading his Suffer the Children when I was 10 and thinking it was shit. I don’t even think I actually finished it, I just remember how terrible it was. I’d just read Stephen King’s Danse Macabre, and he says something in there about never writing about evil kids, or murdering kids, becuase it was a cop out. And I remember thinking, ahhh…he was talking about John Saul.

And then I read Cujo, and thought, wow, that’s just as lazy, the way that ended (no spoilers here though)

Wow, I must have given up on Saul entirely before the brains-in-jars book came out.

Cujo’s definitely not my favorite King, though it was interesting to me that he managed to milk a whole plot out of such a tightly enclosed situation.