Today it’s accepted that fiction (broadly defined; I’m including film and TV) can describe war in a realistic fashion. Stories aren’t required to be realistic, but they’re permitted to be. Until quite recently, that wasn’t the case. (I remember very vividly being called a pornographer of violence by Analog because I was trying to describe war as I’d seen it from the loader’s hatch of a tank in Cambodia.) That may be part of the reason why very few WW II veterans wrote Military SF.

Robert Heinlein and Gordon R Dickson wrote the most memorable military SF of the 1950s, but they had no combat experience. Mr. Heinlein served briefly as a naval officer in the ’30s before being invalided out with tuberculosis, while Gordy had asthma and spent WW II mowing lawns on army bases in California.

There were combat veterans who were prominent in the SF field at the time, but they were not prominent in Military SF. Herbert Gold, the founding editor of Galaxy, had been a grunt involved in the brutal fighting for Luzon, where nearly 300,000 Japanese soldiers were killed, but his magazine was the last place you’d look for Military SF. (Dorsai! was serialized in Astounding, later Analog; while the serial form of Starship Troopers appeared in F&SF.) Similarly Walter M. Miller had flown as air crew in B-25 bomber operations in Italy, including the mistaken attack on the Monte Cassino monastery.

Miller wrote and Gold published Command Performance, a devastating look at how Post Traumatic Stress Disorder feels from the inside, but the form of the story has nothing to do with war or the military. PTSD drove both men out of the SF field before the decade was over, but they were unwilling to confront it directly in print.

Miller wrote and Gold published Command Performance, a devastating look at how Post Traumatic Stress Disorder feels from the inside, but the form of the story has nothing to do with war or the military. PTSD drove both men out of the SF field before the decade was over, but they were unwilling to confront it directly in print.

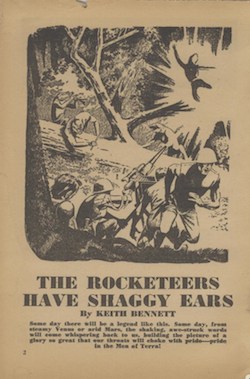

I can only think of one exceptional Military SF story by a (probable) combat veteran before Joe Haldeman, Jerry Pournelle, and I started writing in the late ’60s. That story is Keith Bennett’s The Rocketeers Have Shaggy Ears, which I’m going to discuss in this essay. First, however, I need to provide some background.

2.

For reasons which will become clear, I have to use real names in this essay. I’m going to describe certain incidents as enlisted soldiers believed them to have happened.

Our beliefs may be completely mistaken; certainly they differ considerably from the language of the award citations which the Army accepts as the truth. For the purpose of this essay all that is important is that my fellow troopers at the time acted as though what I’m about to describe was true.

3.

The 11th Armored Cavalry Regiment, the Blackhorse, was the spearpoint of the Cambodian Incursion of May-June, 1970 (the legal invasion, as distinguished from the bombing and black operations which had been going on for years). It was—we were—a crack unit, as fine a combat force as there was in Southeast Asia. The Regimental Commander, Colonel Donn Starry, was in the first vehicle across the border.

The North Vietnamese Army responded by running as fast as it could, but quite early in the operation an NVA soldier was spotted ducking into a bunker. Colonel Starry, with the Regimental Sergeant Major and the regiment’s chief interpreter, decided to talk the enemy soldier into surrendering.

Things seemed to be going well, but the NVA threw a grenade when the Colonel stood up. The blast injured all three friendlies involved in the negotiations as well as the Regimental Operations Officer, Fred Franks, who had just arrived by helicopter. (Despite losing his left leg, Franks went on to command the (coalition) VII Corps in the Second Gulf War.)

According to his award citation, Colonel Starry was wounded in the stomach. According to the medic who worked on him before the dust-off bird—the medical evacuation helicopter—arrived, his most serious wounds were well south of the stomach.

The Colonel was evacuated to Japan. We troopers laughed our collective head off when we heard that the Army had flown his wife there to meet him. To us it was an amazingly cruel joke—and the Army itself had perpetrated it.

You don’t find spit and polish in a real combat unit. You don’t find reverence either. Remember that point.

What happened to that brave NVA soldier? The platoon sergeant rolled his tank up to the bunker and put a round into the opening from as close as he could get the muzzle of his 90 mm main gun. It’s what he would have done first off if the Colonel hadn’t decided to look for a medal. In the Blackhorse we laughed at a lot of things that civilians don’t find funny, but we had no sense of humor toward people shooting at us.

4.

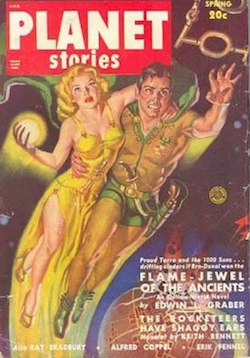

The Rocketeers Have Shaggy Ears was published in the Spring, 1950, issue of Planet Stories. It is the only SF story with the byline Keith Bennett, but three stories over the period 1951-1963 were credited to K. W. Bennett, who may be the same man.

The Rocketeers Have Shaggy Ears was published in the Spring, 1950, issue of Planet Stories. It is the only SF story with the byline Keith Bennett, but three stories over the period 1951-1963 were credited to K. W. Bennett, who may be the same man.

The name isn’t a pseudonym. Harry Harrison interviewed for a job with the editor of a trade journal named Keith Bennett. Harrison asked if the editor was the Bennett who had written Rocketeers. He was—and he was so tickled at the recognition that he hired Harrison.

From context (I won’t put my reasoning here, but I’ll provide it to anyone who asks me) Bennett had been a junior officer in an Army infantry division which fought on the jungle-covered islands of the Pacific. I suspect he commanded a battery of 75 mm pack howitzers.

The plot is simple, as simple as that of the Anabasis: a ship crashes in the unexplored jungles of Venus. The thirty survivors of the crew have to cut their way to their base five hundred miles away. Their equipment includes a light tank, but most of the unit will have to march. They set out.

The viewpoint character is Lieutenant Hague, the young officer commanding the squad with the light cannon. Hague has been rapped on the head during the crash, and his initial observations are fogged, withdrawn. Hague’s emotional distance—his flat affect—continues throughout the novelette, long after the effects of the possible concussion would have worn off.

This flat affect is absolutely symptomatic of someone who has been in combat for any length of time. Civilians—and to my certain knowledge, reviewers who are civilians—tend to assume that material is written without overt emotion because the writer is a monster who doesn’t have an emotional reaction to the (horrible) events he or she is describing. Through Hague’s head injury Bennett, though probably a first-time writer, brilliantly avoided that misunderstanding.

He avoided being misunderstood by civilians, that is. The veterans didn’t need a crutch, because they’d been there themselves.

The unit finds marvels on its way, plants and animals and an abandoned city of cyclopean stonework. Some of the animals become pets, but the troops’ main concern with the city is where to site their cannon for the best field of fire. There are natives also, shadows in the jungle darkness, and they’re hostile.

The troops are under constant stress: from the brutal march, from the jungle and its creatures, from the weather, from the natives. And from the unknown, from fear that doesn’t have a shape yet.

A few men break down; they’re dealt with according to circumstances and to the needs of the unit. Mostly, though, they just go on until they die. A lot of them die.

They help their buddies as long as they can and bury them when help is no longer possible; and sometimes there isn’t even a body bury. The survivors march on.

There are repeated acts of individual heroism which nobody talks about or even thinks about: it was necessary and somebody did it. Maybe it was your turn this time, maybe it was somebody else’s turn. It happened and you survived; and you march on.

I don’t know of any work of fiction which better captures the unrelenting grind of continuous combat operations. Amazing things happen, but Hague observes them precisely, unemotionally. Hague is numb, and his fellows are numb. Everyone subjected to such conditions becomes numb, or they break.

At last the survivors come within reach of safety—they’re in communication with the base and a rescue party is on the way. Here they break into song and Bennett makes a subtle point which he couldn’t address head-on because of the obscenity laws on the books in 1949.

The troops sing The Rocketeers Have Shaggy Ears, and the fact that the song provided the story’s title shows how important it was. The text describes it as ribald and says that the lyrics after the opening line wouldn’t look good in print. This is literally true, but people who don’t actually know the piece in any of its manifestations probably don’t understand how very true the statement was. Certainly the readers suggesting lyrics in the letter columns of later issues of Planet didn’t, and I’m quite certain that Judy-Lynn Del Rey didn’t expect correct answers when she proposed a lyrics contest when Del Rey Books reprinted the story in the ’70s.

The version Manly Wade Wellman sang to me (as The Mountaineers; there are also Engineers, Pioneers, and Cannoneers, which last gave the title to a memoir by a field artilleryman) continues:

And go without their britches.

They pop their cocks with jagged rocks—

They’re hardy sons of bitches.

Further stanzas are of a similar order, but the first is enough to make the point that even today The Rocketeers wouldn’t be a song for polite society. The troops, men who have proved themselves heroic and enduring beyond civilian imagination, are giving the bird to society and to their own brass who are listening back at base. This is humor which deliberately distances the veterans from all those who haven’t paid what they paid.

A real combat outfit reverences nothing. I don’t think anyone can achieve a bone-deep understanding of that without having himself been in such a unit. Keith Bennett understood perfectly, and he made that understanding the point of his story.

5.

Blackhorse firebases—the squadron headquarters in the field, each with a battery of self-propelled howitzers—were often named for senior personnel who had been wounded. At Fort Defiance (a different naming convention: 2nd Squadron had set up in the middle of the Parrot’s Beak and dared the NVA to do something about it) Sergeant Major Burkett was wounded badly enough to be medevacked. Before the dust-off bird arrived, Burkett realized that his shirt was bloody and ran back to his trailer to get a fresh one. While he was inside a rocket hit the trailer, blowing his arm off.

When 2nd Squadron moved, the new position officially became Firebase Burkett. In the field, however, everybody called it Burkett’s Arm.

There was never a Firebase Starry. We troopers believed that the brass was afraid that some journalist would hear us refer to it as Donn’s Dick.

Keith Bennett and his Rocketeers would have understood.

You can read The Rocketeers Have Shaggy Ears here.

Bestselling author David Drake can be found online at david-drake.com.

Would you consider Catch-22 to be realistic? I mean, I know it’s a farce comedy, and designed as a criticism of the military, but the scene at the end with Snowden always struck me as very visceral.

Thank you for this.

I was very much into military SF as a teen, but with time, reading in other places about what war is really like, the techno-heroic-mold stuff really paled on me. And later it did not escape me that SF authors like Cyril Kornbluth, who had seen combat, did not talk about it (this from Pohl’s blog) much less glamorize it in fiction.

Donn Starry died last week.

Cyril Kornbluth saw combat (at the Battle of the Bulge) and he did write about war a little afterwards, though it’s not exactly military sf–e.g. “The Adventurer” (http://www.gutenberg.org/files/29908/29908-h/29908-h.htm) and “The Only Thing We Learn” (http://www.baenebooks.com/chapters/0671698265/0671698265___7.htm).

Dear People,

And before I go any farther–can somebody tell me how to be able to use the same name each time I reply? I’m having to change my name each time I comment because ‘somebody else is using that nickname’. Presumably me the day before.

1) I consider Catch-22 very realistic.

2) Kornbluth’s The Only Thing We Learn brilliantly describes his view (and mine) of war and human history.

3) Col Starry was a very brave man. But I could tell other stories too.

Dave Drake

David,

The simplest way to keep the same name is to register on the site. Once you are logged in it will use the name you pick in your posts.

The Register link is top, upper right.

Dear Shalter (and Irene),

Thank you. I have successfully done that. (Actually, it had been done for me a while ago but I didn’t remember how)

Dave

I never understood that “pornography of violence” crack: it always seemed to me that it was, instead, horror–very good horror at that, and horror of which the most fantastic element was that it happened… happens… and will happen again…

Thanks for the article David. It was quite interesting and informative.

Knew a guy who led a run through family quarters at the top of his voice.

John Dann MacDonald did SF but again not military though there are bits and pieces interwoven throughout his whole body of work. I have no idea what the truth is on where and how Eric Frank Russell served.

Black humor is part of any profession where death is close, I’ve seen it a few times in the response community, and you have to be careful after a disaster to ensure that none of it occurs within the hearing of the families of the victims. Humor, especially inappropriate humor, seems to be a coping mechanism.

Dear People,

I’m going to try another group reply. Keep your fingers crossed.

9) Dr Schmidt states categorically that it isn’t his policy to attack Nam vets; but quite clearly, it wasn’t something that bothered him enough to change. Believe me, worse things happened to other vets, and even to me.

10) Thank you. I try to tell the truth as I know it.

11) From comments he made in PITFCS from ca 1960, Russell was an enlisted man in the RAF.

12) And absolutely yes! A friend of mine was a fire fighter. Boy! did he have stories about that sort of thing.

Dave Drake

What a great essay.

I’m a little nervous about saying this, but I don’t think it is far wrong to assume that every British SF writer of the 1950s had lived in a war zone.

Britain, compared to some parts of Europe got off pretty lightly, but you can echoes of those PTSD effects in a lot of stuff. Is it the proverbial stiff upper lip, or numbness? There are signs of that, and examples of the bleak humour, in “London Can Take It”. (But here I an amateur ticking boxes in a list of symptoms of some mental illness.) That short movie was made as propaganda, but it was made, and signed off on, by people who were there. It maybe seemed more positive to them than it would to an impartial observer.

My mother was no Rosie the Riveter, but she told of dodging Heinkels on the way home from school.

Thanks for the link to the Kornbluth story, JamesEnge!

I agree that the humor on the front lines is about as black as it can be, at least it was when I was in. Nowadays, with all the sensitivity and HR training, I wonder if it is still the same. And I also wonder if the increase in PTSD is because the services have spent so much time humanizing the enemy that it makes it more difficult to cope with doing what you have to do in a war.

Speaking as an outsider, both Dickson and Heinlein strike me as having written military porn– not violence porn. They wrote military sf with too little violence and chaos.

Anyone know whether William Burkett (Sleeping Planet) had military experience? The book had the aliens making some all too plausible errors.

Well, for what little it’s worth, I’m glad there are some people who do write unbowdlerized violence into their stories.

And as a Traumatic Brain Injury survivor, I’m afraid I do understand Post Traumatic Stress Disorder rather well – clinical depression is another name for it, and I suffered that for five years with minor intermissions after I survived my TBI. (For what little it’s worth, I have volunteered for the NZ Territorials – after I felt I had recovered sufficiently from my TBI. I don’t know why they didn’t take me. I honestly don’t.)

However, from my background – PNG-born of expat parents; born in the bush itself, not in any of the lesser or greater towns – I do worry exceedingly about the rabid war-porn of those who write casually about fighting in the land of people who are not themselves involved in that particular war. I naturally consider everything US fiction writers write about Guadalcanal, for example, to be tainted as rabid war-porn – at what point in time did the Guadalcanalese have any say in what foreigners (Japanese, New Zealanders, Americans) were doing in their land? And how was it relevant to their lives?

(For what little it’s worth, I speak from the experience of being told by a couple of locals in PNG, while examining the gas cylinders under my parents’ house, not to go anywhere near the bombs – gas cylinders look like bombs, and bombs had been rather too liberally sprinkled on the basically neutral Papua Niuginians by the Allied (UN) forces (Australian, American) in the latter part of 1943-45. And the extensive munitions clearance that Europe got after May 1945, took so, so much longer to get started in PNG – in 1972, my father was still finding machine gun cartridge belts in the Sepik and handing them in to the Australian Administration.)

Has anyone ever written MilSF from the viewpoint of the unfortunates who have to survive two enemy nation-planets fighting on their land? I doubt any US writer could have the empathy to do that.

Dear People,

14) Thank you.

15) A good point–the best example I can think of, though, is Ballard wo was in a Japanese prison camp. But they’re none of them (that I know of) writing Military SF.

16) Agreed.

17) Don’t get into that ‘our war was worse than their war’ crap. I would be amazed to learn that combat troops today are any more sensitive than we were in Nam or our great grandfathers were during the Philippines Insurection (“They may be Taft’s little brown brothers, but they ain’t no kin to me!”).

18) Charles Platt contrasted my ‘queasy voyeurism’ with Heinlein’s realism, because Heinlein was a combat veteran and I was not. The comment about Heinlein, who spent the war in Philadelphia and Thought Very Hard about kamikazes bothered me as much as Mr Platt’s lie about my own background.

19) Don’t weaken a valid argument with crap. Off the top of my head, look at This Island Earth by Raymond E Jones (three novellas bound as a novel) directly comparing Earth in an interstellar war with Guadalcanal, and The Liberation of Earth by William Tenn, a story. I could find more if I thought it was worth looking.

As always,

Dave Drake

Piling on because I started the post before #20 appeared – it’s not at all obscure

#19 – William Tenn/Philip Klass – combat engineer ETO – The Liberation of Earth published 1953 – inspired by Korea

Publications:

•Future Science Fiction, May 1953, (May 1953, ed. Robert W. Lowndes, publ. Columbia Publications, Inc., $0.25, 100pp, Pulp, magazine) Cover: A. Leslie Ross – [VERIFIED]

•Of All Possible Worlds, (1955, William Tenn, publ. Ballantine, $2.00, 160pp, hc, coll) Cover: Richard Powers

•Of All Possible Worlds, (1955, William Tenn, publ. Ballantine, #99, $0.35, 159+[2]pp, pb, coll) Cover: Richard Powers – [VERIFIED]

•Of All Possible Worlds, (1956, William Tenn, publ. Michael Joseph (Novels of Tomorrow), 255pp, hc, coll)

•Of All Possible Worlds, (Jun 1960, William Tenn, publ. Ballantine, #407K, $0.35, 161pp, pb, coll) Cover: Blanchard – [VERIFIED]

•More Penguin Science Fiction, (1963, ed. Brian W. Aldiss, publ. Penguin, #1963, 3/6, 236pp, pb, anth) Cover: Vassily Kandinsky – [VERIFIED]

•Of All Possible Worlds, (1963, William Tenn, publ. Mayflower-Dell, #6532-8, 3/6, 190pp, pb, coll) – [VERIFIED]

•More Penguin Science Fiction, (1964, ed. Brian W. Aldiss, publ. Penguin, #1963, 3/6, 236pp, pb, anth) Cover: Vassily Kandinsky

•The Starlit Corridor, (1967, ed. Roger Mansfield, publ. Pergamon Press Ltd., 0-08-203370-6, 21/-, xi+145pp, hc, anth)

•The Starlit Corridor, (1967, ed. Roger Mansfield, publ. Pergamon Press Ltd., 0-08-303370-X, 145pp, tp, anth) – [VERIFIED]

•More Penguin Science Fiction, (1968, ed. Brian W. Aldiss, publ. Penguin, #1963, 236pp, pb, anth) Cover: Richard Hollis

•Of All Possible Worlds, (Jun 1968, William Tenn, publ. Ballantine, #U6136, $0.75, 161pp, pb, coll) – [VERIFIED]

•The War Book, (1969, ed. James Sallis, publ. Hart-Davis, hc, anth)

•The War Book, (1971, ed. James Sallis, publ. Panther, 0-586-03430-7, £0.30, 176pp, pb, anth) Cover: Peter Tybus – [VERIFIED]

•Invaders from Space, (1972, ed. Robert Silverberg, publ. Hawthorn Books, $6.95, xi+241pp, hc, anth) Cover: Angela Arnet – [VERIFIED]

•Das Kriegsbuch, (1972, ed. James Sallis, publ. Hammer, 3-87294-032-5, DM 16.00, 190pp, tp, anth) Cover: Eddie Jones – [VERIFIED]

•Science Fiction: The Great Years, (Jan 1973, ed. Frederik Pohl, Carol Pohl, publ. Ace, #75340, $1.25, 349pp, pb, anth) – [VERIFIED]

•The Penguin Science Fiction Omnibus, (Jun 1973, ed. Brian Aldiss, publ. Penguin, 0-14-003145-6, £0.60, 616pp, pb, anth) Cover: David Pelham – [VERIFIED]

•Tomorrow and Tomorrow, (Oct 1973, ed. Damon Knight, publ. Simon & Schuster, 0-671-65210-9, 251pp, hc, anth) Cover: Wendell Minor

•The Penguin Science Fiction Omnibus, (1974, ed. Brian Aldiss, publ. Penguin, 0-14-003145-6, £0.60, 616pp, pb, anth) Cover: David Pelham – [VERIFIED]

•Das Kriegsbuch, (Jan 1974, ed. James Sallis, publ. Fischer Taschenbuch (Fischer Orbit #34), 3-436-01820-1, DM 3.80, 189+[1]pp, pb, anth) Cover: Eddie Jones – [VERIFIED]

•Science Fiction: The Great Years, (Mar 1974, ed. Frederik Pohl, Carol Pohl, publ. Gollancz, 0-575-01784-8, £2.50, 319pp, hc, anth)

•The Liberated Future, (Dec 1974, ed. Robert Hoskins, publ. Fawcett Crest, #Q2329, $1.50, 304pp, pb, anth) Cover: Oscar Liebman – [VERIFIED]

•Vuurwater, (1975, William Tenn, publ. Meulenhoff (M=SF #88), 90-290-0249-2, 248pp, pb, coll) Cover: Chris Foss – [VERIFIED]

•Science Fiction: The Great Years, (1977, ed. Carol Pohl, Frederik Pohl, publ. Sphere, 0-7221-6924-8, £0.75, 287pp, pb, anth) Cover: Peter A. Jones – [VERIFIED]

•Science Fiction of the Fifties, (Sep 1979, ed. Martin Harry Greenberg, Joseph Olander, publ. Avon, 0-380-46409-8, $4.95, xxiii+438pp, tp, anth) Cover: Stanislaw Fernandes – [VERIFIED]

•The Penguin Science Fiction Omnibus, (1980, ed. Brian W. Aldiss, publ. Penguin Books, 0-14-003145-6, £1.95, 616pp, pb, anth) Cover: Tom Stimpson – [VERIFIED]

•Science Fiction of the Fifties, (Feb 1980, ed. Joseph Olander, Martin Harry Greenberg, publ. Avon / SFBC, #3671, $3.98, xxii+393pp, hc, anth) Cover: Gary Viskupic – [VERIFIED]

•The Survival of Freedom, (Aug 1981, ed. Jerry Pournelle, John F. Carr, publ. Fawcett Crest, 0-449-24435-0, $2.50, 381pp, pb, anth) – [VERIFIED]

•The Penguin Science Fiction Omnibus, (1985, ed. Brian W. Aldiss, publ. Penguin Books, 0-14-003145-6, £3.50, 616pp, pb, anth) Cover: Peter Jones – [VERIFIED]

•The Great SF Stories# 15 (1953), (Dec 1986, ed. Isaac Asimov, Martin H. Greenberg, publ. DAW Books, 0-88677-171-4, $3.50, 352pp, pb, anth) Cover: Tony Roberts – [VERIFIED]

•Invasions, (Aug 1990, ed. Isaac Asimov, Charles G. Waugh, Martin H. Greenberg, publ. Roc / Penguin, 0-451-45027-2, $4.95, 382pp, pb, anth) Cover: J. K. Potter

•There Won’t Be War, (Nov 1991, ed. Harry Harrison, Bruce McAllister, publ. Tor, 0-812-51941-8, $3.99, 309pp, pb, anth) Cover: Alan Gutierrez – [VERIFIED]

•Invaders!, (Dec 1993, ed. Jack Dann, Gardner Dozois, publ. Ace, 0-441-01519-0, $4.50, 241pp, pb, anth) Cover: Joan Pelaez

•Immodest Proposals: The Complete Science Fiction of William Tenn, Volume 1, (Feb 2001, William Tenn, publ. NESFA, 1-886778-19-1, $29.00, vii+618pp, hc, coll) Cover: H. R. Van Dongen – [VERIFIED]

•Immodest Proposals: The Complete Science Fiction of William Tenn, Volume 1, (Jul 2001, William Tenn, publ. NESFA Press, 1-886778-19-1, $29.00, vii+618pp, hc, coll) Cover: H. R. Van Dongen – [VERIFIED]

•Immodest Proposals: The Complete Science Fiction of William Tenn, Volume 1, (Sep 2002, William Tenn, publ. NESFA Press / SFBC, #52644, $14.50, 618pp, hc, coll) Cover: H. R. Van Dongen

•A Science Fiction Omnibus, (Nov 2007, ed. Brian Aldiss, publ. Penguin Books (Penguin Modern Classics), 978-0-14-118892-8, £9.99, 592pp, tp, anth) Cover: Jim Burns

•The Wesleyan Anthology of Science Fiction, (Aug 2010, ed. Rob Latham, Veronica Hollinger, Joan Gordon, Istvan Csicsery-Ronay, Jr., Arthur B. Evans, Carol McGuirk, publ. Wesleyan University Press, 978-0-8195-6954-7, $85.00, 688pp, hc, anth) – [VERIFIED]

•The Wesleyan Anthology of Science Fiction, (Aug 2010, ed. Rob Latham, Veronica Hollinger, Joan Gordon, Istvan Csicsery-Ronay, Jr., Arthur B. Evans, Carol McGuirk, publ. Wesleyan University Press, 978-0-8195-6955-4, $39.95, xviii+767pp, tp, anth) Cover: Georges Méliès – [VERIFIED]

•The Wesleyan Anthology of Science Fiction, (Aug 2010, ed. Rob Latham, Veronica Hollinger, Joan Gordon, Istvan Csicsery-Ronay, Jr., Arthur B. Evans, Carol McGuirk, publ. Wesleyan University Press, 978-0-8195-6954-7, $85.00, 688pp, hc, anth) – [VERIFIED]

Not that folks could live on the difference but I thought Ballard was interned rather than imprisoned. It’s not SF but James Clavell has written about his experiences both in fiction and memoirs including a rather Corey Ten Boom epiphany on reconciliation.

David, I wasn’t arguing that one war was any better or worse than another. Hard to find a criteria to make any judgement on that. However, there is no doubt that there has been a huge increase in PTSD and it isn’t all guys gaming the system, or better diagnosis.

What definition of MilSf is being used here? Would Theodore R. Cogswell’s “Spectre General” count? He was an ambulance driver in the Abraham Lincoln Brigade [1]. Arthur H. Landis was also in the the Abraham Lincoln Brigade but I don’t think any of his fiction would count as MilSF.

1: Note for younger reader: Commie Mutant Traitors on the losing side of the Spanish Civil War (Objectively pro-Soviet (2). It was listed on the Attorney General’s List of Subversive Organizations. Having been in the Abraham Lincoln Brigade meant one could not be considered for any sort of commission or positive distinction by the USG.

2: Note that being on a side considered pro-Soviet didn’t mean the Soviets would be pro-[supposed ally]. See also why it was lucky for Orwell he got shot in the neck when he did.

#22 – I’d be interested in figures – numbers – on incidence and visibility.

For visibility at some distance consider the circumstances of the death of Thomas Heggen – we remember Henry Fonda and Jack Lemmon in Mr. Roberts but who knows the name of the author? – and some of the Whiz Kids at Ford and a myriad of other such. I used to know a Belgian who had been the subject of enhanced interrogation by the Gestapo and visibly hated to be backed into a corner at a cocktail party – though he embraced the suck so to speak and avoided the diagnosis.

For younger folks on the situation in Spain consider all the reworkings frex Dr. Pournelle’s His Truth Goes Marching On from Combat SF and later reworkings.

Nancy, I am glad to see a mention of Sleeping Planet by William Burkett. One of my favorite novels of all time, though it appears to have been all but forgotten by most people-I’d love to see that book reprinted sometime. I corresponded by e-mail with Mr. Burkett at one time, and believe his background was in journalism. And I am pretty sure he was a hunter. Not sure about military background.

And Alladin, I am American, and contributed a novelette to Jerry Pournelle’s War World: Invasion anthology from the viewpoint of a congregation of a small church trying to flee the invading forces, and being fortunate to have a retired military man to lead them to safety. So there is one small example to refute your sweeping and insulting generalization that US writers lack empathy for the victims of war.

2: Note that being on a side considered pro-Soviet didn’t mean the Soviets would be pro-[supposed ally]. See also why it was lucky for Orwell he got shot in the neck when he did.

Allow me to clarify: Orwell was not pro-Soviet. When he went to fight in Spain, he joined POUM (Partido Obrero de Unificación Marxista). POUM was one of a number of factions fighting for the Republican government. The alliance also included Communists who were overtly allied to Moscow.

Eventually the Muscovite Communists decided ideological purity mattered more than winning the Civil War and POUM was purged on charges of being Trotskyists and objectively pro-Fascist. Orwell and his wife could have come to a very sticky end had they not escaped from Spain at this point.

Aladdin_Sane, we’ve got one very strong counter-example– a story that meets your specs by an American author, and the story wasn’t just published, it was multiply anthologized.

It’s just as well that you brought the subject up.

I’m not going to be nasty about your not being familiar with Golden Age sf. There’s simply so much sf available these days that there’s no way to keep up with what’s current, let alone read very much of the older stuff.

I do recommend William Tenn in general– he was a very clever writer. This doesn’t mean I’ve read him recently enough to vet him for racism/sexism, so you’re taking your chances.

On the other hand, I don’t think there are a lot of stories which meet your specs. I’ll be curious if more of them turn up in this discussion.

As for empathy, I don’t think people are very good at it generally speaking. I’d be willing to bet your preferred culture/genre just has a different set of blind spots.

Tenn had other stories along the same lines as “The Liberation of Earth”; “There Were People on Bikini, There Were People on Attu”, for example, has the population of Earth removed by a superior civilization so the Earth can be used for a super-weapon test.

#19, 27 – Beyond the obvious and ideal example supra it might be well to set a few limits on what constitutes an example as requested including what makes for MIL SF – especially given my own perhaps lamentable tendency to take a lesson from my betters and assign as space opera what many call MIL SF.

From STOS we have Errand of Mercy by Gene L. Coon.

Does that count? There are several print tales drawing inspiration from Spain with armed men withdrawing on one side of town to lamentations and armed men advancing into the other side of town greeted with flowers.

Not obviously SF there is long tradition in American literature and media seen in the movies Shenandoah and Friendly Persuasion.

Smedley Butler had some interesting things to say himself and some of those stories have had the numbers filed off.

The only discussion in rasfw (a usenet group) which I’d say came to a satisfactory conclusion was the one defining milsf– it’s sf about people in a chain of command.

Wasp isn’t milsf by that definition, and I’d say that neither are the Miles novels.

Clark, I’m not sure what you’re saying about milsf vs. space opera– where would you put the Lensman books?

Dear John (AKA 22),

It is no longer acceptable for generals to slap soldiers with PTSD (shell shock) and call them cowards as Patton did; or for that matter, to shoot them for Lack of Moral Fiber as the British did in WW I.

People are able to be more open about their problems. I don’t think that means the problems are more common.

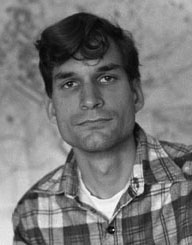

For that matter–take a look at the picture of me at the head of this essay. Do you think I was normal? I sure told people that I was.

Dave

Nancy, I share your admiration for Mr. Tenn, a brilliant writer, and in particular I remember a rather sardonic book about humans suriviving like mice in the walls after an invasion of earth by giant aliens, certainly a metaphor for the helpless victims of warfare.

I’d never heard of the rasfw definition of military science fiction, it is certainly one way to try to put your arms around it. But it leaves out SF stories that look at warfare from folks outside the chain of command, which leaves out some compelling viewpoints. Certainly, if milsf is always written by someone in the chain of command, it rules out by definition any tales from the viewpoint of the victim.

I would disagree with you on Wasp and the Miles (I assume you mean Vorkosigan) novels. While the military man in Wasp was on independent duty, he was absolutely a member of a chain of command, operating under orders, albeit very broad orders. And in the Miles books, Miles is always in some sort of chain of command, sometimes in differing chains of command at the same time, and often chafing against those chains of command. The Miles series incorporates many stories, and many elements, that are clearly not milsf, but a very significant portion of the series is military in nature.

And I would say that, while there is a lot of milsf that is not space opera, and a lot of space opera that is not milsf, there are a LOT of examples of where space opera and milsf overlap.

#30 – Does that put G. Brooks McNye in a chain of command and so make Delilah…. mil.sf?

I’m not sure what I’m saying either. My usage is derived from Mr. Drake as best I understand it – see the odd and incidental writings on his own website maybe search for mil sf and space opera – and there are people much better qualified to speak than I am (Tom Kratman on his own writings) who disagree at least with my own understanding and usage. I’ll grant him his points and maybe that implies distinction by intention which is a useless distinction. Maybe the distinction on the web site cited doesn’t generalize to other writers. Assuredly law school sharpened my own focus by narrowing my mind.

Most assuredly I’d put the Lensman books in space opera – and perhaps more fun to read given that I have strong connections to the Ag school and the town of Moscow – much of which appears. Maybe for a rule of thumb something like the distinction between strategy and tactics but that’s not precisely the distinction just a guide. I am reminded of a couple of recent points ex thread about the Company as the unit of caring – and compare that with the Battalion which is arguably the unit where the Colonel has some authority and yet still can try to know each of his subordinates as an individual. The question of independent operations comes up too. I think there’s a very gray line involving POV, all sorts of size and what size map covers the action but I can’t draw it precisely.

Still it’s hard to draw lines – Zelazny has a couple stories set on a devastated earth involving military style actions at different times in the story and among other elements but from a command perspective. I’d say those don’t count but I’m not sure why.

#32 –

I believe the original was not by but about. I’d be inclined to say a not the victim but that’s another issue.

There’s a short story written and reprinted as SF (perhaps for the market advantages it could be set any time and place) in which a little girl who is nothing and nobody interacts with the supreme commander – (YASID warmongering supremo is saddled with a girl child – somewhat Donde style for those who might remember that comic strip/ graphic by his KIA son and learns compassion and self control for a happy ending to a brief tale and see below, we have a winner – not a U.S. of A. POV. Some say Eric Frank Russell had NSA style tales to swap with Tom Kelly around a campfire some say Eric Frank Russell sat in a radio trailer and learned from the traffic; as noted I don’t know). Such tales of victims exist be they ruled in, out or corner case from our given category. Perhaps if this thread is to veer from humor to a catalog of empathy by writers from the U.S. of A. (compared and contrasted with others) then a consensus on what we mean when we say it or point to it without explicit rules is as good as it gets. I’m not sure what the POV is in the Star Trek episode I cited with a query. Does it in fact qualify? It would have been a glorious war.

Edited once for the story id.

David, I had exactly the same idea about the shellshock, just didn’t write it. And as for normal, we all have issues, it is how we deal with them that defines us.

I, too, would highly recommend Sleeping Planet. One of my fave books ever and I dig it out and reread it every few years. I wish Burkett had kept on writing instead of taking off 20 years until his next novel, because it wasn’t nearly as good. In addition to it being a good yarn, it is very funny to me.

Nancy, if you vet stories that were written years ago for racism and sexism, you pretty much eliminate all the classics. Trying to put modern sensibilities on older novels just doesn’t work. Just as an example, reading Tarzan stories by ERB still are great adventure stories, but you will see a lot of racism and sexism. Would you stop reading Mark Twain? Tennessee Williams? Faulkner?

IIRC David Weber defined “MilSF” as Science Fiction written with characters that reflect the military POV, military mindset, military structure, etc.

The story referenced by ClarkEMyers at #34 in this thread is probably Eric Frank Russell’s short story, “I Am Nothing,” originally published in the July 1952 issue of Astounding Science Fiction. It’s been reprinted in the NESFA anthology of Russell’s short fiction, Major Ingredients.

As always, thank you David. There are a lot of us out here who appreciate your contributions and meeting you was memorable. For me, at least. :P

Tom

Well, thanks, everyone, for the comments on my comment.

I can see why I’m not that comfortable with MilSF a bit clearer now – people I have known have usually been nearer the bottom of that particular pecking order than otherwise. The only exception I can think of was my step-grandfather, who was an engineer aboard an RNZN cruiser during the Second World War, but he always saw himself as being at the bottom of that particular pecking order, having to carry out stupid commands from technically-ignorant superior officers …

To tie black humour and empathy in a bit tighter, though – you need empathy to enjoy humour. You need to be able to see that such-and-such a situation is bollocksed-up from the POV of the people in that situation, to share their humour. People at the top of the pecking order are (in)famously incapable of empathy with those below them – the gag in Bill The Galactic Hero, during battle, where the superior office bawls out the fuse-changers for other-than-spotless uniforms, is an example.

And we, whose empathy is with the fuse-changers, get the black humour of that moment.

Which ties in rather well with the the Shaggy-Eared Rocketeers, doesn’t it? All we need to have a complete view of the horrors of war, is the view from the people who aren’t involved, who don’t want to be involved, who just want to get on with their lives …

And thanks for that title: Eric Frank Russell’s “I am Nothing”. I’ll go look for it.

Alladin, People at the top of the pecking order in the military often have more empathy than you give them credit for. Much of what gets blamed on heartlessness or thoughtlessness from higher brass is simply the inefficiency of any large and complicated social structure.

39 – Dean Jagger Major General Thomas F. Waverly in the movie White Christmas has a line about being at Anzio is not a free pass to get out of wearing a tie. There’s a reason for gig lines and such when clean socks might well be a matter of life and death some day – for want of a nail…….

Oddly for folks who have some associations of hearing it in the south Pacific one of the saddest songs ever written is White Christmas.

Aladdin @19:

You know, that doesn’t make a lot of sense. Locals caught up in a larger conflict almost never have any say about the troops that are fighting in their area. That’s pretty much true by definition, because if they did have a say, the war wouldn’t be being fought in their neighborhood. Substitute “Belgium” for “Guadalcanal” and it comes out the same.

“Relevance to the lives of the locals” is an even more recondite point. The issues of the Pacific Theatre of WWII may not have had the well-understood immediacy for residents of Guadalcanal that the Civil War had in Mississippi, but both the World Wars were fueled by colonialism, and Guadalcanal, which had been part of the British Solomon Islands Protectorate since 1893, was certainly in play. After the Japanese invaded, the fighting had even more relevance.

Given that you’re making hairsplittingly fine distinctions in what has so far been a polite discussion, could you please refrain from ornamenting your remarks with phrases like “tainted as rabid war-porn”? It’s out of scale, entirely unwarranted.

That sort of talk is also unwelcome because it gives encouragement to wander-in commenters who just like saying nasty things, many of whom have gotten the idea that discussions of military service are an all-seasons target. We’ve had enough of that the last few days.

@39:

Of my own certain knowledge, I know you to be wrong about that.

Also, you’re citing an anecdote from a humorous work of fiction.

I don’t mean you’re just a little bit wrong. I mean you’re thoroughly and completely wrong. There are documented instances of a lack of empathy, but you can find those in any population. As a general principle, though? Not true.

This is a serious discussion. Please take it seriously.

Johntheirishmongol @22, I think the soaring incidence of PTSD is still well within the range of better diagnosis, plus less social pressure to deny that it’s a problem. When you start looking closely at things said about veterans of previous wars — for instance, that long after the Civil War, it was enough to explain someone’s aberrant behavior to say “he was at Shiloh” — it pops up everywhere.

The veterans themselves may not have talked about it, but when you read old family histories, you get glimpses of their families’ profound confusion and distress: Uncle Ed just wasn’t right after the war. I got my brother back, but he was different. James would never talk about his time in the service. He’d always been so gentle. The doctors said he was all right, but–. He wouldn’t talk to us. He’d get these moods on him. I married him anyway, hoping things would get better. You get a sense that there’s a huge amount of quiet suffering.

Given that wars and the military aren’t going to go away in the foreseeable future, I’m glad we’re finally addressing it.

David Drake,

First, I wanted to tell you that I buy your books automatically upon publication. I think I have read practically everything you have ever published, and I expect I always will. The reason is your attempt to be honest and authentic in your descriptions of characters and situations, and your willingness to look unflinchingly at things like PTSD and ‘combat numbness’ and its consequences, even when doing so may not be popular or commercially ‘safe’.

On ‘combat numbness’ and black humour, as you describe it in this excellent column, one of the best snapshots of it ‘in progress’ that I have ever read is a book called “Some Desperate Glory” by Edwin Campion Vaughan. First published in 1981, it is Vaughan’s daily diary of the first 8 months of his service in WW1. He starts the diary on January 4, 1917, as a 19-year-old wet-behnd-the-ears officer joining his regiment in the trenches with a copy of Palgrave’s “Golden Treasury” in his pack and a belief in the playing fields of Eton in his heart (well, actually, he was fresh from a Jesuit prep school, but same difference). When he gives up on the diary on August 28, 1917, after 75 of his 90-man company have been killed at Passchendaele, he sounds 119-years-old with not much belief in anything.

Two sentences in the diary still stick with me after 30 years:

January 4 [leaving Waterloo train station on the way to the front]: When we had swept round the bend, away from the crowded platform, ringing with farewell cheers, I sank back into the cushions, and tried to realize that, at last, I was actually on my way to France, to war and excitement — to death or glory, or both.

April 24 [after 4 months in the trenches, Vaughan and another officer go to do salvage work on a position their company occupied a couple months earlier]:

I had a look at one old shelter behind Desiree and saw that the one from which Dunham had got ice for our tea, was full of green water in which lay a rotting Frenchman [dating from 1916] — yet our tea had tasted quite good.”

In civilian life, people sue restaurants and manufacturers for huge sums because a quality control error let some random foreign object slip past inspection and wind up in their food or drink, resulting in ‘mental shock and trauma’ that apparently scars them for life. Here, after 4 months of combat operations, Vaughan finds the discovery that he has been drinking liquified Frenchman worth noting only because liquified Frenchman apparently does not ruin British tea. Now that’s combat numbness; probably WW1 British ‘Tommy’ black humour too.

John Hardy

Dear Mr Hardy (44),

Thank you.

My fiction was a tool to keep myself mentally between the ditches. (I wasn’t conscious of this for a long time, but it’s obviously true.) Prettying up the truth to gain the approval of folks like Stanley Schmidt wouldn’t have helped me at all.

Except, of course, to make sales. Which is much less important than keeping out of jail or worse.

Best wishes,

Dave Drake

John Hardy: Thank you. I’ll have to read Vaughn’s memoir.

I’m sure you’re right about what Vaughn meant by his remark about the tea. It occurs to me in addition that when ice forms slowly, it throws off impurities. If Dunham knew that, he may have deliberately collected ice from the shelter because he knew he could find hard, clear, comparatively clean ice there.

It would have been a useful trick to know in the trenches. There can’t have been much standing water at Passchendaele that hadn’t been in contact with corpses.

David Drake @@@@@20: I’ve noticed that minor characters named Charles Platt appear in many of your novels, invariably as sleazy little villains who come to sticky ends. So that’s what he did to earn a place on your list of Names of Perpetual Dishonor. I had wondered.

tnh @@@@@ 46: I think you’re right that using ice probably did serve as an impromptu filter and that this probably was a useful trick in winter trench conditions. On the other hand, if you offered most Western civilians a cup of tea and told them the water was drawn from that pond over there with the rotting corpse in it, but before using it you had first filtered it with the latest high tech ceramic filter, then chlorinated it, and then distilled it for good measure before boiling it for the tea, how many would pick up the cup?

So David (and anyone else i guess), do you think good Military SF (or really, military fiction of any kind) can be written by someone who has not experienced some form of military or trauma? I.e. by someone who has had a peaceful life?

Also – love love love that you have a kick-ass librarian in your Lt. Leary series.

PS – #44, way to go with the primary source

Dear Vyrm (47),

Irene initially suggested that I might do a historical overview of Military SF for my essay. I wasn’t sure what I would do, but I rejected that possibility immediately.

Yes, I have the knowledge base to write about the subgenre as I wrote about Golden Age SF for a Nebula anthology. But–I didn’t _write_ SF in the Golden Age. People might disagree with me, but they couldn’t claim I was beating my own drum.

They certainly would if I discussed MSF; and they might have been right, because I’m human.

This is a long way of saying that I’m not going to answer your question. I have my own opinions, yes; but the subject is so intensely emotional for me that I do not feel that my opinions would have any validity outside my own head.

Dave

DavidDrake,

Well done, I enjoyed the essay above, thank you.

On the point of humor in today’s Combat Arms units, rest assured it still exists.

Addressing the lack of empathy or cold hearted actions by the brass and senior Enlisted, it happens, as has been said their are people who truly do not care about anyone else throughout society.

If you haven’t served then you can’t possibly understand how the military rank structure works, how Officers, NCOs and Enlisted interact even in the midst of combat. We take care of our own and those that cannot or will not are taken care of in our own way.

Late to the party… for some reason (hah.. subterfuge), I didn’t seem to want to dive into the comments.

Thanks David. I’d have to say, for what it’s worth, your books, as an innoculant, probably helped in my time in the Army. I was an interrogator (16 years), and well, you sort of know how that goes.

Thu humor at the sharp end, is no different than it was, and havig seen the elephant, I can tell when someone else has been there; a lot better than I could before. If we’re ever at the same con, I’ll buy you a drink, or we can stand a couple of rounds, because I owe you.

Other than that, I don’t know what to say. The subject is, perhaps, still a little tender, and I don’t really want to poke at it in print.

Thanks again.

One thought on the prevalence of despicable Platts in Mr. Drake’s writing: Mr. Platt’s progeny appear to have spread throughout the human multiverse, because they’re everywhere. Does that serve as post hoc vindication for Mr. Platt? He would seem to have all of the cockroach’s virtues as well as its vices.

The Rocketeers Have Shaggy Ears is one of my favorite stories, introduced to me by my father, who kept a considerable collection of pulp science fiction magazines in the garage.

As a matter of historical record, here are the lyrics to the first song presented by David Drake in the anthology Space Infantry (edited by David Drake) in the introduction:

Mars was met and conquered,

Venus also fell –

But it’s still ever onward,

Into the gates of Hell.

The Rocketeers have shaggy ears,

They’re dirty sons of Space

They drink and smoke and fight and swear

They’re the strongest of our race!

And then there’s the other song, shared with Drake by Manly Wade Wellman. To be continued.

In the interest of the historical record, here are the lyrics to The Mountaineers Have Hairy Ears (as related in the Space Infantry introduction), from which The Rocketeers Have Shaggy Ears has some sort of descent.

(To comply with the Moderation Policy I have adjusted the words somewhat.)

The mountaineers have hairy ears,

They go without their britches,

They pop their c***ks with jagged rocks,

They’re hardy sons of bitches.

They screw the wh***s right through their drawers,

They do not care for trifles –

They hang their balls upon the walls

And shoot at them with rifles.

Much joy they reap by di***ing sheep;

In diverse nooks and ditches

Nor give they a da*n if it be a ram –

They’re hardy sons of b****es.