In August of last year I wrote, somewhat crankily, that

…Our technological society’s one big blind spot is that we can imagine everything about ourselves and our world changing except how we make decisions.

By this I meant that we avidly consume stories where the entire Earth is eaten by nanotech, or where bio-genetic revolutions change the human species, or where cheap space flight opens up the universe—but these futures are almost always ruled over by autocratic megacorporations, faceless bureaucracies, voting democracies or even hereditary aristocrats. (After thousands of years of civilization, that galaxy far far away still keeps slaves.) Technology changes in SF, and even human nature gets altered by implants and uploading and perpetual life—but how governments work? Not so much.

I said I was accusing society in the above quote, but actually the people I was accusing of being most vulnerable to this blind spot were science fiction writers. It’s true there are plenty of Utopian futures in SF, but the vast majority of books within the sub-genres of cyberpunk, space opera and hard SF contain regressive or static visions of human conflict in the future. We’ve given them license to break the barrier of lightspeed, but not to imagine that some other organizing principle could replace bureaucracy or—even worse—to imagine that we could without tyranny reduce human conflict down to a level of ignorable background noise.

All of these futures now face a problem.

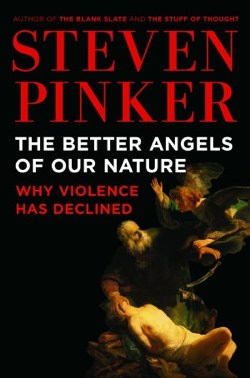

It would be convenient to dismiss Steven Pinker as a lone voice in declaring that human violence has vastly declined over the past half-millennium and continues to do so; the problem is that he does not bother to make that argument in The Better Angels of Our Nature. Instead, he lets the numbers do it for him. Better Angels contains literally dozens of graphs where the line starts at the top left and ends up literally bottoming out on the right; no form of human violence has been exempt from a nearly 100-fold reduction in the past thousand years. (The past was demonstrably not better than today: where ever you live, the murder rate 100 years ago was probably ten times what it is today, and 1000 years ago, it may have been 100 times what it is now.) There may be a lot to argue over in The Better Angels of Our Nature—and there is in fact much that deserves to be argued about—but the overall trend is not one of those things. And if you write science fiction about the future, this is going to present you with a problem.

Certain facts and ideas become constraints on us when we write SF. In Dune, Frank Herbert famously invented the Butlerian Jihad—a war against artificial intelligences and robots in the distant past—so that he could write about a future in which humans still use other humans as servants and slaves. Ever since Asimov, writers who use robots have had to contend with the possibility of the 3 laws or their equivalent. And currently, anybody writing about the next fifty years has to either have some sort of technological singularity, or at the very least explain why one hasn’t happened.

Of course fiction runs on conflict, as Larry Niven archly pointed out in his classic short story “Safe at Any Speed.” A conflict-free future is hard to write about. Nonetheless, this is exactly what humanity may be facing, because while once again there may be many things we can argue about in Pinker’s book, the overall trend is not one of them. Almost the entire world is participating in a trend whose line is direct and clear. It’s incomparably safer out there than it was a century ago, or even ten years ago. Pinker shows that even when you factor in the genocides and millions of deaths from events like the Second World War and the famines in China and Russia in the 20th century, that century was still less violent than the 19th; and the 19th was less violent than the 18th and so on. (His numbers become dodgy when he pushes them past antiquity, because while a large percentage of prehistoric humans died violently, many of those injuries are of the same type that are incurred today by rodeo riders, implying that hunting big game was as likely a source for bashed-in skulls and shattered limbs in that era as war. Nonetheless, while we can accuse him of exaggeration at times, the main trends within historical time are not exaggerated.) The 21st century is, so far, the least violent period in all of human history, and the trend is continuing.

Nobody knows where or whether this trend will stop. What we do know, according to Pinker, is that many of the easy explanations for it are wrong. Access to weaponry does not itself cause violence (it turns out that it really is true that guns don’t kill people, people kill people). Resource clashes (the classic cause in geopolitical thinking) are only loosely connected to violence in history. Affluence itself does not make people less violent, nor does poverty make them more so. And religion’s effect on violence throughout history has been, well, neutral when taken altogether. What this means is that you can’t justify a general future that’s more violent (or even one that is still as violent as the present) by making it the product of nuclear proliferation, economic depression, or religious fanaticism. If society is decaying, as some conservative thinkers would have us believe, then it is decaying in the direction of universal peace and harmony. Even the looming catastrophe of climate change contains no inevitable amplifier of the known causes of violent behaviour in humans.

Pinker takes a stab at defining those causes. He’s probably not entirely right; it’ll take a lot more anthropology, economics and cognitive science to root out the real reasons for the decline in violence. What does seem clear, though, is that those reasons are so deeply rooted in who we are as people today, and how we experience our world, that almost no conceivable event could immediately reverse them. (A global nuclear war or comparably extreme event might put intolerable pressure on our civility, but it would take something on that scale because whatever it is, it has to simultaneously strike at multiple reinforcing trends.) Fascism and communism and the industrialization of mass murder; vast governmental corruption and statewide propaganda systems; centuries of demonization of the enemy by states and churches; depressions, famines, wars and plagues—none of these factors either singly or in combination have been strong enough to reverse the steady trend toward civilization and peace among human beings.

For us as SF writers, this fact constitutes a new constraint that we have to acknowledge. These days, if you write an SF story set thirty years in the future without either having a technological singularity in it, or having an explanation as to why one hasn’t happened, then some fan is going to call you on it. After learning about the scope and robustness of the historical trend towards peacefulness (and once again, Pinker’s not the only author of this idea) I’m not going to buy into any SF story about a future where societal violence or war are even holding steady at our level, without the author at least coming up with some mechanism stronger than ideology, religion, economics, resource crashes and poverty, or a proliferation of arms to explain why. Pinker’s analysis suggests that multiple mutually-reinforcing virtuous circles are driving humanity to greater and greater degrees of civility. In order to write a credible violent future, you’re going to have to show me how these break down. And because the steadiness of the historical trend shows that these reinforcing circles are not vulnerable to the obvious disruptions described above, that’s not going to be an easy task.

Is it time to add the decline of violence to the Singularity and other constraints on the credibility of our futures? —Of course we can write about any damn future we want, and we will. But after Pinker’s book, it’s at least going to be clear that when we read about futures involving unexplained endemic social, governmental and personal violence, that what we’re reading is probably not science fiction, but fantasy.

Karl Schroeder has published many novels through Tor Books. He divides his time between writing science fiction and consulting in the area of technology foresight. He is currently finishing a Masters degree in Strategic Foresight and Innovation. Karl lives in Toronto with his wife and daughter, and a small menagerie.

While one would hope that would be the case, I don’t see you will see it happen in the near future, or anytime in the forseeable future. Stories without conflicts aren’t stories, they are travellogues, and usually boring at that.

There are some interesting stories that don’t have identifiable conflicts. Mostly they’re “how it happened” or “how they did it.”

No reason a story can’t recognize that the future is more peaceful, but here in Story X we run into one of those cases where violence does happen. And we’ll certainly continue to face conflicts that we resolve without resort to violence.

I think that you are going too far on requiring speculative fiction written about future scenarios to account for the possible decreasing human or societal tendency to violence. Many of these future narratives are really a disguised critique of current conditions or absurd satirical projections of what current conditions could lead to and were never meant to be accepted as true or plausible futures.

I think a good example of this is Star Trek, a setting in which human society has evolved into one in which conflict mostly comes from without (alien civilizations, etc.). Of course, the technology is mostly fantasy, but still…

I do think that if you are writing a predictive sci-fi story that this point of credibility is valid. But so much of sci-fi is actually about what happening now, told in a futuristic parable–and in cases like this I think you can write a credible piece of a violent future.

Still, a very interesting exploration…thanks!

And we’ll certainly continue to face conflicts that we resolve without resort to violence.

Quite. Even if you rule out Man vs. Man, that still leaves you Man vs. Universe. (obsolete terms, yes, I know.)

You can still write fiction with violence for the same reason that everyone outside of a relatively small club feels comfortable writing about a time after Kurweil’s hypothetical party kickoff date- because actual growth and decay curves are sigmoid, and lumpy, and ubiquitous macro trends don’t always manifest at the micro scale in the ways you expect. There will still be enough violence to tell violent stories for those who are interested in such things.

That being said, I’ve had this thought before, and it means that writers like Kim Stanley Robinson, whose fantastical playground was always really more about SFnal changes in the decency of human affairs than it was about Mars or the like, were on to something.

Hi Karl.

This reminds me of one of the “dream conversations” in Waking Life, where one of the people the dream protagonist listens to talks about how society might evolve in directions similar to this.

Pinker’s numbers are terribly overinflated for the past, especially on the military side of things. Ancient sources reported enormously large and uncredible numbers (E.G. the only sources we have for the Persian army invading Greece in the 5th century are Greek. Shockingly, they overestimate the size of the invading army, probably by a factor of a thousand.) Pinker swallows these numbers wholesale. The result is a massive misjudgment on the number of casualties in ancient wars.

@9 He also discounts that many of the famines in Russia and China in the past century were not natural disasters but the economic policies of a government trying to eliminate a political class ie the Kulaks, or a misguided ‘Great Leap Forward’ and Cultural Revolution.

We only glimpse a small snapshot of the United Federation od Planets. Somewhere there are camps like the one in Auckland that held Tom Paris where those that are politically incorrect are ‘rehabilitated’.

All of these futures now face a problem.

Really? After one book refuting them?

I hope Pinker’s correct, but here’s another perspective, suggesting that, “A sceptical reader might wonder whether the outbreak of peace in developed countries and endemic conflict in less fortunate lands might not be somehow connected.” That the world’s superpowers have simply exported their conflicts to the developing world in much the same way as we export our pollution.

@the last comment: The numbers show conflict has declined in Africa, Asia, and Latin America at the same time it has gone near-extinct in, say, Western Europe. And the facts Pinker gives can be found elsewhere, including a more narrowly focused recent book “Winning the War on War.”

I wouldn’t be too complacent about this – as Pinker himself points out, WWI and WWII were a major temporary reversal of this trend, so there could be others.

But so far things are, in fact, getting better, in this way and others.

Criticism on Pinker’s analysis aside, I believe the trend of decline in violence, even if proved correct, does not mean a decline in conflict. Assuming the kind of neo-medieval world which seems to be emerging will be another enduring trend, it is easy to imagine the conflicts between the various competing power centers would assume the shape of espionage, sabotage, corporate boardroom scheming, and political maneuvering, coupled with black ops, selective assassination, terrorism, and electronic warfare, but always stopping short of outright war. I believe one of the reasons that may explain the decline in violence is the emergence of asymethrical warfare as the new standard in war, contrasting with the massive, industrial warfare of the 19th and 20th centuries. Violence is limited because one side is always too powerful to be faced head on, so more subtle (and less lethal) forms of violence have to be used to win.

There is a type of plot that is being overlooked here – the “X meets

Y” or its equivalent, “X meets dreeh (i.e. alien)”, and how do they resolve that? Plenty of SF/F to date has had that plot, and could continue to do so, against a backdrop of less or no violence.

Yeah, I know, it’s called a romance.

Let me just briefly mention something that seems to have been overlooked — “conflict” doesn’t need to be “violent”. Possibly there are issues to making that exciting to readers — but I doubt it. Even “murder mysteries” aren’t mostly about the lives of the protagonists being at stake.

But what I really wanted to say here is that a more and more important factor is crazy people. Unless something changes drastically, they’re going to continue to exist. As we live less and less cheek-by-jowl they will get noticed later and later. And as the energe budget available to individuals increases, they’ll do more and more damage if their craziness eventually leads them to violence (note that I’m NOT assuming all craziness leads to violence; it doesn’t of course). So when I read about societies where each individual controls an energy budget equivalent to a couple of stars, I wonder how often planets get volatalized by some crazy person.

I don’t see any obvious reason for insanity to decrease as society advances; if anything, it’s been increasing throughout my life (as we redefine “eccentricity” upwards, often). In the long run, less insanity is a good social goal — but individual monitoring and control is NOT a good goal. Kind of a conflict, there.

@15: It’s easy to see the lone lunatic problem going critical as the tools of biotechnology become more and more accessible. Perhaps a ubiquitous surveillance state is the natural extension of this trend towards absolute personal safety.

I’m sure that the Ethiopians and Eritreans would be surprised to hear that, as would (going back a decade or two), the Rwandans. So too would the Serbs, Croats, and Bosnians.

As to the numbers, anything before 1945 is highly suspect and usually inflated, and using it as definitive and comparative evidence is dangerous, indeed.

Well, good lord, if you can identify WWI and WWII as a “temporary reversal” you can pretty much decide anything you want. How does Pinker deal with the Holocaust? The Soviet purges? Mao’s Great Awakening & Cultural Revolution? The Khmer Rouge? “Minor setbacks”?

Interesting article, but this:

And I’m going to laugh at them, just as I would a similar demand for astrological content. I know you have that degree in futurism, KS, but come on. It vitiates an otherwise compelling argument, the same way a discussion about space exploration would be marred by talk about how new discoveries will change horoscopes. (Which is a topic that exists.)

“How does Pinker deal with the Holocaust? The Soviet purges? Mao’s Great Awakening & Cultural Revolution? The Khmer Rouge? “Minor setbacks”? ”

I haven’t read the book, but the most obvious ‘deal’ is long term averages. The number of people killed is horrifically huge. But the number of people alive to be killed is also huge, and on the scale of a century, a horrible 5 year period starts fading away. Percentage-wise, killing a million people out of a billion is nothing compared to killing one person in a tribe of 30.

Karl: if one insists on extending trends into constraints, there’s worldwide dropping fertility rates, leading to an expectation of eventually no humans and certainly no space colonies. I haven’t seen anything outside of some Japanese SF take that into account.

“these futures are almost always ruled over by autocratic megacorporations, faceless bureaucracies, voting democracies or even hereditary aristocrats.”

This seems like an odd set. It’s not like voting democracies have been ubiquitous in history. We’re living *in* a SFnal future…

In my heart, I hope that Mr. Pinker proves to be correct. But rationally, I see his theory to be somewhat shaky, and would not expect a conflict-free future for mankind. We have avoided using them in great numbers, but in the past century, we have developed many means of killing people in numbers unimaginable in the past. And if we kill ourselves off in droves by refusing to admit that our actions impact the climate, as some people see in our future, does that count as violence?

I remember once saying to an arms control expert, “Thank God we were able to get past the collapse of the Soviet Union without it triggering a nuclear war.” He looked at me sadly, and said, “Not yet.”

Somehow I think Mr. Pinker’s theories are as overly optimistic as

Francis Fukuyama‘s premature announcement of the End of History.

Okay, several points here:

–Steven Pinker doesn’t have a theory that violence is declining. Violence is declining; he presents some theories as to why, most of which aren’t his. While there is much dodgy data about violence pre-20th century, he spends a lot of the book’s 800 pages analyzing that data and shows pretty conclusively that there is still a major and ongoing decline.

–Yes, the decline is there–and is still huge–even if we take into account the world wars of the last century, recent genocides, and current violence around the world.

–Yeah, the Singularity example wasn’t great–not least because I’m a huge critic of the Singularity myself and am happy to ignore it in my own work. Mea culpa. A better example might be demographics itself: if you want to write about a near-future world where the population is only 5 billion, you’ll probably need to say how that can be. In other words it’s not that a violent future is impossible, but that it now needs justification where we never seemed to think it did before.

–SF is often (even usually) commentary about today disguised as stories about the future. I’m saying that if you really do pretend to be writing about the future, then the decline in violence is a constraint you need to take into account. (But, you know… a book about the present that’s disguised as a book about the future should, one would think, be truthful about present facts: one such fact is that this is the most peaceful era in all of human history. So your allegorical ‘future’ world should be extraordinarily peaceful too, shouldn’t it?)

–To put it as clearly as I can, you can still be as violent as you want in your future fiction, provided that violence is justified by plot circumstances. It’s just… it now needs to be justified.

A better example might be demographics itself: if you want to write

about a near-future world where the population is only 5 billion, you’ll

probably need to say how that can be.

By the hoary beard of Darwin, did Warren Thompson teach us nothing? NOTHING???!!!!

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Demographic_transition

If I wanted a future where there were only five billion people, I’d presume no Stage Six exists and use a model like the low population extrapolation in this toy model:

http://www.un.org/esa/population/publications/longrange2/2004worldpop2300reportfinalc.pdf

Except I might also toss in a failure for TFR to rebound the way they have it doing above.

Note how the UN low population model dips below five billion in the first half of the 22nd century.

James: I don’t think of 2300 as the near future, do you? Nor the first half of the 22nd century. Perhaps I should have been specific with my dates, but really… How plain does my language have to be to not be misinterpreted?

Uh, I don’t think that’s true. A society of 1000 people that executes 10 of its members seems to me to be unexceptional. A society of 100 million that executes a million of its own people seems to me horrifying. Yet, they’re the same percentages.

And I’m suggesting that that theory–espoused by Pinker and others–is largely hogwash, based on enormously overinflated numbers from past times that get included without much effective skepticism about them.

Actually, I do re: the 22nd. It’s not much farther away than the Great War is now and I knew Great War vets as a kid.

How plain does my language have to be to not be misinterpreted?

Actual dates might be useful.

Total: If you read my original posting, you’ll see that I agree with you that much of the historical data is hogwash. If you study other analyses, for instance Beyond War: The Human Potential for Peace by Douglas P. Fry, you find very different interpretations of prehistoric violence. The first several chapters of Pinker’s book are very weak in this respect.

However.

Once we enter historical time periods, Pinker has much better data to draw on, and he chooses his sources carefully. There is a lot of data out there that is not hogwash, and it all supports the basic thesis that violence has radically declined and is continuing to decline. You can of course choose to go on calling it all hogwash without actually reading Pinker’s book, examining his sources, or following his references… but if so you’ll be using what’s known as ‘the argument from incredulity’ which goes ‘I don’t believe it, so it can’t be true.’

Do you really want to go there?

For additional conversation fodder, have the Human Security Report:

http://www.hsrgroup.org/human-security-reports/human-security-report.aspx

I think Jack McDevitt does a good job portraying a future like you describe in many of his novels. There is still some individual conflict, but it is rarely violent.

A simple extrapolation of current trends gives you a declining world population within the lifetimes of people already around; it’s virtually inevitable, unless you have some sort of game-changer, asteroid-impact level thing. The World TFR will drop below 2.1 within the next decade. As for the Singularity, I’ve never found it either a) credible or b) interesting, so I just ignore it and any posthumanist objections. You can make a very good argument, which I believe, that in terms of actual impact on human life, technological change is slowing down — 2012 is much more like 1962 than 1962 was like 1912. Likewise, we’re not getting less violent, we’re getting more closely governed. Historical rates of violence were very high because people weren’t prevented from acting that way. Throw in that nuclear weapons broke the 20-year cycle of the World Wars and you’ve got all the explanation you need.

nce we enter historical time periods, Pinker has much better data to draw on, and he chooses his sources carefully. There is a lot of data out there that is not hogwash, and it all supports the basic thesis that violence has radically declined and is continuing to decline. You can of course choose to go on calling it all hogwash without actually reading Pinker’s book, examining his sources, or following his references… but if so you’ll be using what’s known as ‘the argument from incredulity’ which goes ‘I don’t believe it, so it can’t be true.’

Wow! Do you get this defensive so quickly all the time?

As a matter of fact, I have not read the book thoroughly, but I have looked at citations, bibliography, and the data he cites, and I’m not just randomly asserting things when I say it’s crap. He relies on dodgy evidence (and this is just as true for recent history as it is for earlier times; the man uses wikipedia in a number of places, for God’s sake), he handwaves away the world wars, and his assertion that deaths as a percentage of population as the most important measure is ridiculous (there is a difference between a nation of 1000 that kills ten of its own people and a nation of 100 million that kills 1 million of its own citizens, yet the percentages are the same).

I get that you thought you had a nice hook here, but you don’t, and patronizing anyone who points out its flaws is just shaming yourself.

I just think that, if only the 20th century is the only sample with reliable data, and we know that violence comes into history in fits and starts, that it is far too small a sample to be thought reliable.