Tor.com comics blogger Tim Callahan has dedicated the next twelve months to a reread of all of the major Alan Moore comics (and plenty of minor ones as well). Each week he will provide commentary on what he’s been reading. Welcome to the 17th installment.

September 1986 was an enormously important month for American superhero comics. Quantum, Zzzax, and Halflife teamed up to battle the West Coast Avengers. Starfire learned about racism in the pages of Teen Titans spotlight. Swamp Thing came to Gotham City. Watchmen #1 debuted. And Alan Moore killed off Superman forever.

Okay, some of those things may not be that important in retrospect. And some of them are not even true. I mean, those comics had a “September 1986” cover date, but they would have come out a few months before that, and with the vagarities of cover-dating and release schedules, they may not even have hit the stands during the same month, in real life.

Plus, Superman didn’t really die, and Alan Moore didn’t really kill him, but Moore did end the character’s life, and his two-part “Whatever Happened to the Man of Tomorrow?” story, from September of 1986, put a nail in the coffin that was the pre-Crisis Superman. After that, it was all John Byrne and tattered capes and hugs from Ma Kent.

As much tongue-in-cheekiness as I have in my opening paragraphs this week, it is a fact that Alan Moore wrote four American comic books that hit the shelves with that same September 1986 cover date. And it wasn’t just any four. It was the fallout from the epic battle in Swamp Thing #50 (with issue #52, showing Arkham Asylum covered in Swamp Thing overgrowth), and that was a good comic, but it was also the month where the still-legendary Watchmen first popped up, in front of an unsuspecting public.

How were readers at the time to know that superhero comics’ Citizen Kane was making its first appearance?

And to release, with the very same cover date, the end of Superman? To symbolically “kill off” their nearly-omnipotent flagship character to make way for a fresh, more humanist approach? Bold moves from DC.

Had the internet existed at the time, the world may have reacted with a resounding “meh,” but the internet wasn’t around so we actually got to appreciate the interesting stuff that we saw all around us. Like the first issue of Watchmen. And that time Alan Moore tried to fit all Superman stories into one last Superman story.

Alan Moore had written Superman comics before, of course. Last week, I wrote about his DC Comics Presents issue in which the Man of Steel sort of teamed up with Swamp Thing. That came out one year before Moore’s final Superman tale. And while September 1986’s “Whatever Happened to the Man of Tomorrow?” running through Superman #423 and Action Comics #583 was the end of an era, the final story before John Byrne relaunched and rebooted Superman and cut away most of his history before later writers would build it back up again, it wasn’t Alan Moore’s best Superman story.

No, like the one-shot from DC Comics Presents, this other Superman comic came out the year before Superman’s pre-Crisis, pre-reboot, last hurrah.

The story was “For the Man Who Has Everything,” and it stands as one of Alan Moore’s best comic book stories of all time.

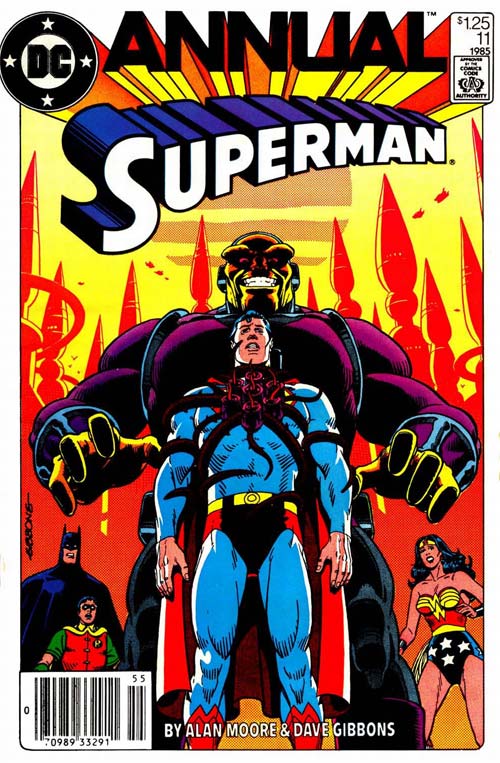

Superman Annual #11 (DC Comics, 1985)

Drawn by perhaps Alan Moore’s best artistic collaborator, Dave Gibbons, “For the Man Who Has Everything” takes place on February 29th, Superman’s birthday. A long-standing joke in comic book circles (and jokes in comic book circles are notoriously hilarious, are they not?) revolved around Superman’s eternal youth, with one explanation being that he looked so young for so many years because he only had to celebrate his birthday every leap year. Ha!

Moore took the idea of a Superman birthday and turned it from a comedy premise usually, in these type of stories, some misunderstanding leads to mishaps, and some twist reveal clears everything up at the end and wrote a genuinely melancholy story about moving beyond the tragedies of the past.

Some of the trappings of the story echo Watchmen I can’t help but wonder if the Fortress of Solitude setting of the story inspired Moore and Gibbons to place the showdown with Ozymandias in a similarly exotic arctic secret base but, as powerful as “For the Man Who Has Everything” turns out to be, it’s not a somber, “realistic” story.

It’s sci-fi, of the Golden Age of Sci-Fi variety, but with deep emotional underpinnings and deft characterizations.

The concept is simple: Batman, Robin, and Wonder Woman show up to the Fortress of Solitude to give Superman some birthday presents. Seems like a dorky story out of 1958, more than 1985, right? But what they find is a Superman trapped inside his own mind. He’s a victim of the “Black Mercy” an alien plant life attached to Superman’s “bio aura” thanks to the menacing space villain known as Mongul.

Just as he did in the Superman/Swamp Thing team-up, Alan Moore provides a piece of alien vegetation as the means through which to explore Superman’s psyche. He forces his hero into inaction, and puts us inside his tortured mind.

But while in the DC Comics Presents story, he was trapped in hellish delusions, here his mind has given him everything he has ever wanted. He’s back on Krypton, having grown to adulthood with his birth family. His home planet was never destroyed. Kal-El has a wife, and children. Everything is perfect.

Except, it’s not. Jor-El has become a bitter old man. Political extremists cause trouble in the streets. Life is a struggle. Kal-El sometimes wishes that his father had been right all along. Maybe things would be better if the planet had just blown itself to bits.

Yet, even as Superman begins to realize that his dream life as challenging as it may be might be a lie, he holds his young son and cries, telling him, “ I don’t think you’re real.”

Moore and Gibbons cut back and forth between the dream world and the real, physical conflict in the Fortress of Solitude as Batman, Wonder Woman, and even Robin, kick, punch, and blast the menacing Mongul.

The brilliance of the story is in its telling, of course, and the way Moore and Gibbons take a hoary sci-fi/fantasy/fairy tale cliché of wish granted and then let the characters really inhabit that wish-reality for just long enough to make the emotional pain palpable. Had this story actually been published in 1958 and for all I know, there may have been a Superman story or seven in which he dreamed he was still living back on Krypton the Krypton dream sequences would have been short, and declarative. Here, they breathe. Superman, as Kal-El, has time to suffer the indignations of his alternate reality, but the real catch is that he also has time to feel regret at what he lost.

The ending of the story isn’t “it was all just a dream!” The ending of the story is that Superman remembers living another life, one in which Krypton survived with him on it, and that memory, and the pain, will live with him forever.

Or, at least until the following year, when the ripple effect from Crisis on Infinite Earths would reshape the DC Universe, and that Superman would be wiped away.

Superman#423 and Action Comics #583 (DC Comics, September 1986)

Take note of this: Watchmen was just beginning to come out as this story debuted, but because of Moore’s bold splash on the American comic book scene, with Swamp Thing and whatever else trickled over here from England, he was entrusted with writing the last Superman story.

Perhaps his work on the previous year’s Superman Annual helped DC editorial make that call, but it’s certainly a choice that would have been seen as controversial by anyone following the comics industry at the time. Here’s a writer with barely any connection to the character, and he’s coming in to write the final story before a new writer and artist start over from scratch? The customary approach would be to just throw an old-timer on the comic, or to let the series whimper and die before the relaunch. But DC’s choice for Alan Moore to provide the capstone on their lead character shows unusual canniness. They knew how important he was in the grand scheme of things, even though his most influential work had yet to appear.

But the unfortunate fact about the two-part Superman finale, “Whatever Happened to the Man of Tomorrow?” is that it’s not a particularly great story. It’s not even a particularly great Superman story.

Drawn by practically eternal Superman artist Curt Swan and inked by George Perez, it’s worth reading, as a historical curiosity, and it’s not a completely terrible final Superman story, but in Alan Moore’s attempt to pay tribute to the character, he turns the two-parter into a list of stuff that happens, all of which are acting as Silver Age callbacks and not particularly interesting as scenes.

The structure of the whole thing does have some fascinating elements to it, even if it doesn’t actually scan as an engaging story: it escalates, with everything going wrong for Superman and the tragedies mounting, until the final confrontation with the real mastermind behind the whole domino-effect of badness.

It turns out that the being behind all the horrible events in Superman’s life, from the death of Bizarro to the exposure of the Clark Kent secret identity, from the attack of the Metallo Men to the murder of Jimmy Olsen all these things had been caused by Mr. Myxzptlk.

Some say that the final reveal was even lifted from a relatively obscure 1977 novel called Superfolks which has elements in common with Moore’s “Marvelman” serial as well.

Whether Moore read, or was influenced by, that novel or not, “Whatever Happened to the Man of Tomorrow?” is too much of a laundry list of allusions and drive-bys and not enough of a substantial story.

And it doesn’t quite sustain its own internal logic, either, even by retro-Silver Age Fifth-Dimensional imp standards. In the final scene of the story, before the epilogue, Superman kills Mxyzptlk, ostensibly to stop the now-pure-evil other-dimensional being from causing even more devastating damage to the world, but really for revenge. And then, since Superman doesn’t kill, and doesn’t believe in killing, he has to kill himself.

But as the epilogue shows, he survives, perhaps stripped of his powers, but still alive, living happily ever after with Lois. And sporting a moustache.

The Superman-in-disguise winks at the reader in the final panel, closing the door (literally) on the history of the character.

“Whatever Happened to the Man of Tomorrow?” wants to have it both ways, with its goofy underpinnings and its vicious consequences, but because the story is almost all escalating plot events and then the epilogue, it ends up having nothing but a checklist of Superman memories. Maybe that’s enough.

But it’s not as good as the classic “For the Man Who Has Everything.” Not even close.

And while the Fortress of Solitude setting of the Superman Annual may have inspired Act III scenery in Watchmen, the disguised-Superman-with-a-moustache echoes the final fate of Dan Dreiberg, a.k.a. Nite Owl. So the Watchmen parallels, or reflections, keep popping up. Maybe it’s time to confront that series head-on.

Enough with the Swamp Things and Supermen. It’s time for Dr. Manhattan and his crazy crew of misfits.

NEXT: Finally! What you’ve all been waiting for! Watchmen Part 1

Tim Callahan writes about comics for Tor.com, Comic Book Resources, and Back Issue magazine. Follow him on Twitter.

The Internet most certainly did exist in 1986. I’m not sure if it was called the Internet yet, but there were people online discussing things, even if mostly they were university students and people working for computer companies. I didn’t get online myself until 1988, but I read archives of the Watchmen discussions that took place on Usenet at the time, and they went pretty deep.

This one scene was one of the most powerful I remember from any Superman comic book, it really encapsualtes the sense of loss not often touched upon by other writers when it comes to Kal-El being an orphan. The scene is so powerful in its simplicity. I first read it over 20 years ago and it still sticks with me to this day. I think For the Man Who Has Everything is, for me, the best thing Moore’s done with superheroes he did not create. I re-read the issue at least once a year.

I love the JLU animated adaptation of For The Man Who Has Everything, even though it leaves out a lot of the details in order to get through the plot in under half an hour, and suffers more for the relative shallowness of the Mongul slugfest. The most important moments are done extremely well. In particular, the scenes of the characters’ dreams falling apart are more heartbreaking than ever.

With you on For the Man Who Has Everything, but have to say that I really liked Whatever Happened to the Man from Tomorrow. I’m not a massive comics fan and not a Superman fan at all, I bought a trade edition of the stories because they were by Alan Moore, not because they were Superman. So I found Whatever Happened to the Man from Tomorrow a rather charming farewell to a character with cheerful nods to some of the more obscure characters and liked the wink and the crushing coal to diamond at the end.

Whatever happened too? is not a great story, What is great is that a Superhero genuinely no kidding. Ends! Even in 1986 superhero death meant little. This was not about death this was the Superman that existed from 1954 to 1986 being OVER He’s not just dead his whole story (universe) is over.

I’m sure I’m biased by my unwavering love of Superman in general and the Silver and Bronze ages in particular. But I think Whatever Happened to the Man of Tomorrow? is underrated here. It’s a near-perfect sendoff to the Silver Age incarnation of the character, giving each supporting character a curtain call and a chance to establish who he or she was before sending them to their (mostly final) fates.

It’s not flawless: Luthor deserved a bigger part than he got. (Though that’s partly redeemed by that last callback to the Smallville teenager he was, begging his old classmate Lana to put him out of his misery.) Curt Swan was the only artist for this project, but the disturbing and eldritch thing Mxyzptlk became at the end was just outside his range. (Something confirmed for me when I saw his work on an early New Teen Titans story: he and Perez used a nearly identical model for Trigon, but Perez’s looked demonic and scary and Swan’s… didn’t.) The early bit with the Prankster, Toyman, and Pete Ross was a little too 80s-brutal in a way that didn’t quite fit. (Though I still liked “Do you know what radio waves look like?”)

But Moore’s little twist on all those “This is an imaginary story” intros was lovely. I found the different ways his friends dealt with the oncoming threat affecting. (And later tracked down the issue Lana’s magic lake water and costume came from.) I’ll always remember Superman and the Legion discussing the implications of knowing one another’s futures, as the equally foredoomed Supergirl and Invisible Kid chat in the background. And anyone who can read Superman telling his late cousin, time-traveled from her youngest days, that “Supergirl is in the past” with dry eyes has no soul.

(“Do I grow up to be pretty?” “… You grew up beautiful.”)

It’s hard for me to imagine a better capstone for that incarnation of Superman. This wasn’t the place for a radical reimagining a la Marvelman or Swamp Thing: that would be left to John Byrne. The plot may not have been Moore’s most complex. But it lays down a legitimate mystery, answers it fairly, and finds a satisfying resolution. Not a bad record, I think, for the last and best of the Imaginary Stories.

It also helps to remember that…

1. At the time these were the current versions of these characters. If you read it now it’s just an au

2. Also remember the purest version of Byrne’s reboot lasted 8 years while the Superman Moore ended lasted 32. Reading that in 1986 meant more than it can now .

Yep, the Internet existed in 1985/6, generally considered to have become “the Internet” on 1/1/83 when what had been ARPANet started using the TCP/IP network protocols. ARPANet, generally considered the direct predecessor of Internet, goes back to 1969. One of the first big, widely distributed mailing lists on ARPANet was SF-Lovers, which started around 1977 or so (and was given a special award at the 1989 Worldcon for being the start of online sf fandom), which occasionally included comics content.

Oddly enough, I happened to receive a link to the Usenet net.comics/rec.arts.comics Watchmen discussion today. Available in gzip files at ftp://ftp.white.toronto.edu/pub/white/pub/cks/comics/watchmen/

Whatever Happened… did something I didn’t think was possible. It gave dimension to even the stupidest characters, and imparted some real depth and weight to bleeding Jimmy and Lana.

Nobody loved him better.

I enjoyed Whatever Happened to the Man of Tomorrow, but I get that it is probably better remembered for its impact than its own strengths.

In hindsight, it was the first draft of an idea that Moore would spend a good portion of the next decade and a half refining. Moore wanted to merge Silver Age inventiveness with the Bronze Age relevance. His last Superman story was a crude combination of call-backs and “realistic” consequences. Moore went back to that well with his run on Supreme. That was a comibation of Silver Age callbacks and metatextuality. The ultimate expression of (so far) that idea was Tom Strong. That series felt Silver Age-y without any direct callbacks, but was modern in its sensibilities.

When you place the Superman Annual against the final Superman/Action Comics stories, something has to come up short in the comparison. The themes are so very different – the Annual speaks to kids about being adults while the final Superman/Action issues speaks to adults about being kids once more. If each of these could be addressed separately (yeah, Tim – another week added to the original plan), the value of each of these contributions to Superman lore would greatly increase.

In support of the ‘final Superman stories’, I wish that prior to the reboots that have occurred since then had a homage like Moore’s that brought the era to a close (instead of a closet-cleaning crisis).

But, Tim – keep up the great work; you’re forcing dialogue and a critical evaluation of this seminal writer (and redefining his place in comics history).

Krypto’s death is maybe my favorite death scene I’ve ever read in a comic book. Oddly powerful considering it was Superdog, Krypto sacrificing himself to kill the Kyrptonite Man and protect his master and the Fortress of Solitude was quite moving on a few levels.

It seems that Moore had a lot he wanted to accomplish and characters he wanted to visit, but only had two issues to do it in. Still, I think it’s rather brilliant and a landmark in neo-silver age stories

I love the re-reads, but I think you don’t do ‘Whatever happended’ justice. This is the perfect send-off issue with a lot of great moments. How could it be any better? I first read it 2 decades later and I reminded me of the time I actually liked Superman, Curt Swan’s art and silver-age DC comics…I hated that stuff in the 80’s and ever since. Alan Moore was able to do the impossible – to give me some kind of reconciliation with this era. Genius.

You know, this is perhaps the twentieth review/appreciation of For the Man Who Has Everything that I’ve read over the years, and I’ve yet to see anyone raise the obvious question: Why did Superman’s vision of Krypton degrade into a dystopia?

The Black Mercy is supposed to produce the victim’s perfect-paradise as a honey-trap–and the silver-age derivation of Krypton that Moore is riffing off of was generally presented as a scientific near-utopia that the parasite plant would hardly even have needed to improve on. Given Mr. Moore’s obvious affection for that version of Krypton, why would he so demean it?

My theory is that Krypton’s societal collapse, (and particularly Jor-El’s personal descent into extremism and madness) represent Superman’s subconscious rejecting the false reality. Whatever else he is, Superman is fundamentally a fighter. Bruce’s external manhandling of the plant may have helped the process a bit, but in the end, Superman freed himself. True heroism.