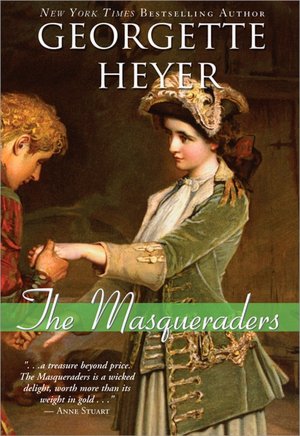

Heyer wrote The Masqueraders, a cross-dressing gender romance with plenty of sword duels, while living in Africa with her then-engineer husband. (He would later choose the less physical job of barrister.) The book is a testimony to her extraordinary memory; despite having no access to her research library, the book contains almost no historical errors. It tells the story of a brother and a sister who, to prevent the brother from getting hanged as a Jacobite traitor, disguise themselves as…a brother and a sister. It’s best to just roll with this. Under their false names and switched genders, they swiftly enter London society without a hint of suspicion. Again, roll with it. And as if things weren’t complicated enough, their father, or, as they call him, the old gentleman, has returned to London, claiming to be Robert Tremaine, Viscount Barham, with the ever so slight complication that Robert Tremaine is supposedly dead, and another cousin is claiming the title. But never to worry. As the old gentleman reminds us, he is a great man. A very great man.

That claim might even be true.

Also, duels! Daring rescues! Masked encounters!

As it turns out, years of complicated schemes have made Prudence quite adept at cross-dressing and masquerading as a man, aided by her height and experience, which helps explain why most people accept her without question as Peter Merriott. Robin does not seem to quite have her experience—Prudence remembers having to train him to walk and talk like a lady—but his small stature, quick wit and ability to flirt stand him in good stead. Again, almost no one suspects. The one exception is Sir Anthony Fanshawe, described by Heyer as a large, indolent gentleman, underestimated by, again, nearly everyone except Prudence.

Heyer may not have realized it at the time, but in Sir Anthony Fanshawe she was creating a character that she would return to on multiple occasions: the gentle giant of a hero, continually underestimated thanks to his size, which leads people to assume a lack of intelligence. In the case of Sir Anthony, this underestimation is doubled since Sir Anthony is not just tall, but also somewhat fat. Heyer plays on the assumption that a fat man not only lacks intelligence, but also skill at swordplay and the ability to rescue damsels from carriages and participate in wild schemes. Her later gentle giants would sometimes lose the weight (especially as Heyer became more and more obsessed with tight-fitting male clothing), but never the underestimation—or the competence.

Prudence and Robin, however, represented something Heyer would not try again—a man and a woman who successfully infiltrate their opposite genders: so much so that Robin becomes the girlish confident of the young Letty before embarking on a career of desperate flirtation, and Prudence finds herself welcomed at the very male enclaves of gaming clubs generally barred to women. She also finds herself challenged to a duel, which she quietly and competently accepts. I must admit that although I realize Sir Anthony’s reasons—and seeing him able to take down the bad guy in a duel has its moments—I’m definitely disappointed that we never do get to see Prudence wield her sword in a proper duel. It’s all the more disappointing since yes, unlike most Heyer heroines, she is competent with a sword, and Sir Anthony and Robin, who is only pretending to be a woman, do get to duel—with Robin’s duel getting Prudence nearly imprisoned and in need of rescue. Which, given her cool competence elsewhere, is also marginally irritating—although at least she participates—physically— in her own rescue. With a sword cane.

But apart from dueling, Prudence is otherwise fully a man while in London. Heyer had of course had the cross-dressing Leonie before this, and would later have the cross-dressing Pen (in The Corinthian), but both of these entered the male world as boys, not men. Prudence would not be her last heroine to enter a male world as an equal, but she was the only one to do so as a man.

She likes, and doesn’t like it. She is pleased that she can pull of the role so successfully, and, as far as we can tell, greatly enjoys the company of men. At the same time, she speaks more than once of being tired of the masquerade and notes, rather wistfully:

“I believe I’ve fallen into a romantic venture, and I always thought I was not made for it. I lack the temperament of your true heroine.”

True heroines, according to Prudence, do not take up swords and fight duels; they wait to be rescued. This speech and others suggest that Prudence believes that her time spent as a man (not just within this book) has ruined her for a usual gender role. It is one of many reasons why she initially declines Sir Anthony’s offer of marriage. At the same time, it says something that both Sir Anthony and Heyer disagree with this self-assessment. Sir Anthony wants to marry Prudence anyway (although he wants her to return to wearing skirts) and Prudence takes up several more pages, and more of the plot, than the character with the temperament of a true heroine, Letitia.

Here and elsewhere, Heyer demonstrated that in her opinion, some women could be the equals of men and stand in their world, but that did not mean the women necessarily should, or would even want to. Prudence happily embraces her return to a woman’s role, and never suggests for a moment that she will try to be a man again, instead embracing—whatever she may think of the word—a romantic role.

Initially, Robin appears to enjoy his role as a woman, flirting outrageously, dancing, playing with fans, making friends with Letitia—but he chafes in his role, more than Prudence ever does. For a very good reason: as a woman, Robin/Kate is restricted in where she can go and what she can do. These restrictions may not bother Prudence, born to be a woman; they certainly end up bothering Robin, who unlike Prudence, breaks his role more than once to play a (masked) male part. Neither expresses any intention of switching genders again once the masquerade is over.

On a related note, I find myself torn between amusement and mild annoyance at Sir Anthony’s confession that he discovered Peter/Prudence’s true gender after discovering an “affection” for her, since, of course, Sir Anthony couldn’t possibly be attracted to a guy or anything like that—no, the only explanation for his attraction to this cool young man is that the man just has to be a girl. That this turns out to be completely true doesn’t change that I rather miss the Duke of Avon’s ability to see through Leonie’s disguise through perception, not attraction, or that a moment or two of Sir Anthony questioning his sexual orientation might have been amusing, if generally unthinkable for Heyer.

But if individually Prudence is one of Heyer’s most competent and likeable heroines, and Sir Anthony a model for her later heroes, the more satisfying romance, oddly enough, turns out to be between Robin and that romantic heroine Letitia. This oddly because their romance more or less works like this: “Oooh, you’ve lied to me throughout this book, wooed me using a mask AND used your fake identity to get personal information out of me. And murdered someone right in front of me! How ROOOMMMMMAAAAAAANTIC!” And yet, Heyer actually manages to pull this off—by creating a character in Letitia who actually WOULD find this stirringly romantic and wonderful, and thus, managing to persuade readers that this is, in fact romantic. At least for Letty. (The rest of us will just be over here banging our heads against the nearest convenient wall.) And to be fair, Letty does seem to be the sort of person who is going to need to be rescued, frequently, so it’s just as well that she’s matched up with the sort of person who is going to need to rescue people, frequently. It does, however seem odd that even in a book where Heyer created a heroine who could be a man, she still insisted on keeping this idea of the girl who always needs rescuing.

What makes this book, however, is not the cross-dressing Robin and Prudence, entertaining though their antics are, or their respective romances, but rather Heyer’s creation of my lord Barham, to give him the title he claims so magnificently. In the course of a colorful life, the old gentleman has enjoyed a number of careers: gambler and owner of a gambling house, fencing master, Jacobite traitor, terrible husband (he admits to giving his considerably lower class wife a hellish time), and a father who is convinced his children will never appreciate him. This in turn has given him a sense of self-worth that leaps beyond arrogance and pride. As he constantly reminds everyone, he is a great man. A truly great man. Not that anyone, he complains, truly appreciates this:

“I have never met the man who had vision large enough to appreciate my genius,” he said simply. “Perhaps it was not to be expected.”

“I shall hope to have my vision enlarged as I become better acquainted with you, sir,” Sir Anthony replied, with admirable gravity.

My lord shook his head. He could not believe in so large a comprehension. “I shall stand alone to the end,” he said. “It is undoubtedly my fate.”

Criticism rolls off him (when confronted with his—very few—failures, he assures everyone that they are “forgotten”). Errors in dress and manner do not. He is never at a loss, even when confronted by a blackmailer demanding a rather significant sum of money:

“…But I don’t think you’ll haggle.”

“I’m sure I shan’t,” my lord answered. “I am not a tradesman.”

“You’re a damned Jack-of-all-trades, in my opinion!” said Markham frankly. “You assume a mighty lofty tone, to be sure –”

“No, no, it comes quite naturally,” my lord interpolated sweetly. “I assume nothing. I am a positive child of nature, my dear sir. But you were saying?”

The conversation only improves from here, though my lord confesses to a touch of disappointment that the blackmailer is so easily led into a trap:

“No one knows me,” said my lord austerely. “But might he have descried that in my bearing which speaks greatness? No, he was absorbed in the admiration of his own poor wits.”

These little clips hardly do him justice: my lord Barham is Heyer’s first truly great comic creation, so successful that she later based some of her comic villains upon him. But none of them reach Barham’s greatness, perhaps because they were copies, perhaps because although Heyer allows these later villains to speak with the upper classes, she never allows them to truly enter or dominate beyond the written page, the way my lord does so unhesitatingly.

I have to admit: my first reading of The Masqueraders was somewhat ruined for me by all the praise I’d seen heaped upon it. On subsequent readings it has significantly improved, not merely because I can now see how Heyer was carefully developing plot techniques and characters that she would use in later book, but also because each time I read it I become more accustomed to Heyer’s elaborate language—something she would later drop as she developed the arch tone that became the hallmark of her later work. Here, the verbiage is often too self-consciously antique, the cant sometimes hard to follow, and the plot often just too ludicrous. Nonetheless, the sheer humor of the novel—and the presence of my lord—allowed the novel to sell very well indeed, and I find myself appreciating it more and more on each reread, while decrying the fact that it would be four years before Heyer allowed herself to work in a humorous vein again.

Time to skip a couple of books again:

Beauvallet (1929): Heyer’s attempt to write a novel set in the Elizabethan period while using Elizabethan language, with, bonus pirates! Alas, the book turns out to be mostly proof that Heyer had no gift for writing either Elizabethan language or pirates. (Or, Spanish.) Worth reading only for Heyer completists, despite some decidedly Romantic with a Capital R moments.

Pastel (1929): Another comtemporary novel, interesting mostly for its statements on gender, the roles of women, which greatly mirror some of the thoughts expressed in The Masqueraders: that it is silly for women to view with men, or worse, attempt to pander to men and attempt to be like them: “Ridiculous! Who wants to be a man!” The now (happily) married Heyer also has her protagonist choose happiness over passion, and realize that her marriage can work despite the lack of romantic love, a theme she would take up again in A Civil Contract.

Next up: Barren Corn.

Mari Ness recently spent some time watching the women’s fencing at the Olympics, and remains in awe. Based on watching those women, she’s pretty sure that Prudence could have easily kicked ass in any duel.

I love, love this book. It is my comfort read of all comfort reads. I have to admit, I’d never envisoned Sir Anthony as fat. More of a tall, broad sort to my mind.

Cassandra

Oh, I was trying to decide what Heyer to pick up next, and I think this settles it. I’m such a sucker for cross-dressing plots, and double-cross-dressing? Better yet!

I have to admit, I tend to see Sir Anthony as being more the tall, bulky style of man (more like a weight-lifter physique than a fencer – barrel chest, solid musculature, built like a brick outhouse), myself. The type of man who isn’t actually carrying much fat, but who always looks as though he would be.

I think the thing which always appealled to me about Prudence was that she was just so calm about all the diverse alarums which are occurring around her. Nothing phases her, nothing flummoxes her, nothing even puts her out in the least. Clearly after years of living with her father and brother, she’s learned to take life as it comes (rather than planning and over-planning things in an effort to try and keep ahead of the chaos).

I agree that Letitia is a little too “Romantickal” for my tastes, and possibly for Prudence’s as well (but then again, Prudence is going to be becoming a Fanshawe, while Letitia will be becoming a Barham, and that means they’re not going to have much to do with each other most of the time). I tend to feel that Letty in later life would either turn into someone like Lavinia (from The Black Moth) or childrearing would settle her a bit, and she’d become like either Elizabeth Ombersley (from The Grand Sophy) or Arabella Bridlington (nee Haverhill, from Arabella).

Sir Anthony Fanshawe “fat”??Bite your tongue!! Megpie71 has him described nicely. Large,perhaps bulky, but never, ever, fat!

The Masqueraders is one of my favorite Heyer books and I re-read it often.

And you are right that dear old dad just makes the book. I loved him (while being quite surprised that neither Prudence or Robin had murdered him in his sleep! He was a Most Difficult Parent!!).

I also have a fondness for Beauvallet. It helps to picture it as an Errol Flynn swashbuckler (perhaps The Black Hawk), complete with Korngold sound-track.

I like the characters in this book, but the plot is so dumb that I tend to cringe when I reread it — so I only do so when I do a complete reread of all the Heyers I own. I can’t even call it an idiot plot, because the characters aren’t idiots. But it’s a series of contrivances that don’t really hold together.

I finished a reread of this one recently; I’m about three-quarters of the way through reading all the Heyer ebooks (in alpha order except for the linked ones) that Sourcebooks put on sale last year. Alas, somehow I missed purchasing An Infamous Army, so I now have the choice of paying $15 for it or reading it in hard copy.

I believe that Sir Anthony looks just like my husband, and so he is quite perfectly large and comfortable, much like a huge stuffed bear.

This is one of my favorite Heyers. The plot is outrageous, but then it’s a comedy so that’s allowed. And My Lord has to be read to be believed.

I actually figured out the logic behind the Robin/Prue switch some time ago. Robin is actually the one who needs a deep disguise, lest he be fingered as a Jacobite, so he becomes “Kate.” But since two “young women” traveling by themselves is just asking for trouble, Prue becomes “Peter” (which she is quite practiced at doing) and provides the necessary “male escort.”

@everybody Well, I did say “somewhat fat.” I don’t think Sir Anthony is incredibly obese. But Heyer emphasizes not just his height, but his width and his largeness, and that people underestimate him because of the width and largeness. He is regularly assumed to be out of shape; his abilities with a sword surprise everyone. Meanwhile, no one is surprised when slender Robin does athletic deeds.

@Barb in Maryland — I find the language in Beauvallet difficult to get through, even with trying to take an Errol Flynn/piratey approach.

@carbonel and margedean56 — Oh, I got the need for Robin to go into hiding, while still needing a male escort. But it’s still ludicrous, as Carbonel points out, not to mention that John or the old gentleman could provide the male escort, while disguising Robin and Prue as two sisters. In real life, Bonnie Prince Charlie managed this stunt for only a couple days at most, and other fleeing Jacobites did not have the time to manage the incredibly close shaves and adaptations of women’s mannerisms, not to mention finding elaborate aristocratic clothing that would fit to pull off a masquerade of this length.

Oh, it’s a silly plot, but the characters are wonderful and the denouement is totally satisfying. Of all the 18th-century Heyers (vs. the Regencies), this is my favorite and I’m glad I’m not the only one.

It’s interesting how different the effect is when there’s a cross-dressing man as well as a cross-dressing woman in the story. I think the historical ‘girl dresses as boy’ scenario, written in the 1920s or later, is an example of the writer having their cake and eating it: while very risqué behaviour for the time in which the story is set, it’s no big deal for the readers in the time in which it’s written. Male cross-dressing, on the other hand, was still pretty startling to contemporary readers.

It’s interesting also how this one work features actual danger in the aftermath of rebellion; I think her works generally present both 18th century and Regency English society as far more settled than they really were. From the ease with which the 18th century characters go to Paris, you’d never realise how often the UK and France were actually at war with each other during that century.

@Tehanu: My favorite of the 18th century Heyers is The Talisman Ring. That’s not to say I don’t like The Masqueraders, just to say that I think The Talisman Ring is subtler and funnier and better done overall.

@Azara: I think you’re onto something when you say Heyer’s works generally present 18th-century and Regency society as being more settled than they actually were. I remember reading a book by Maria Edgeworth or somebody (I don’t rememer exactly, but in any case, a Regency writer actually cited by Heyer) and thinking that the London society she depicted seemed much more ad hoc and provisional than the society shown in Heyer’s books.

@Azara and @etv13

My assumption has always been that Heyer’s eighteenth and nineteenth- century society has always been a fantasy world. The fabulous clothes (which would not have been washed), the bon mots (which would not have been quite that sparkling or as easily tossed off), the cold, bored aristocrat who falls in love with his charming wife, all these elements are escapist fantasies. That’s why they are fun to read because we don’t have to consider the dirt, the smells, and the real brutality of that society. We have Austen for much of that, I suppose.

The business of the cold aristocrat picking his young wife out for convenience was beautifully written about in Amanda Forman’s _The Duchess_. The movie was very well done too and shows very clearly how miserable that charming young girl could be when her cold aristocratic husband does not fall in love with her.

Don’t get me wrong, I do love Heyer and as I posted above this book is one of my favorites. It is a marvelous escape into a world that never really was.

Cassandra

I’ve now bought the book and read it, and rate it as a nice solid three-star Heyer. Prudence is an absolute delight, Robin is juuuuust cute enough to get away with being an impulsive idiot, and of course their father is so wildly over-the-top as to move through annoying back to charming again.

But I confess, I didn’t like Anthony much at all. He was entertaining at the start, but around the time that he set up his “friend” to be fleeced–quite deliberately, and making sure they both knew it was happening–because of an invitation turned down, well. He went from being a confident, interesting man to a controlling asshole who would punish people for not indulging him. And quite frankly, I never lost that opinion; he’s pretty damn high-and-mighty about how of course whatever he wants will Inevitably Submit To Him just because he wants it, and Prudence agreeing that, gee, of course he’ll get his way and be in charge, just said sad things about how far the cultural memes got to her. Poor Prue.

@cass: Sunita at Dear Author recently reviewed A Civil Contract, and it’s interesting reading the comments how many people don’t like it because it’s not fantasy-like enough (even though the hero’s an aristocrat and the heroine’s a mega-heiress). Most of Heyer’s books, especially the eighteenth-century ones, don’t have that problem.

The Masqueraders is a problem for me. There’s so much I like about it, but I just cannot accept the switch back to their own genders at the end. I can completely accept Pru and Robin successfully fooling everyone (except the ‘large gentleman’) in their cross-gendered roles. However, I just can’t believe that they could then reenter society in their correct genders as the children of their father, and not have people recognize them as siblings ‘Peter’ and ‘Kate’. Robin says something to the effect that he was always careful to dress his hair a certain way as a woman as if that alone makes him unrecognizable, but that’s really the only attempt that I remember at explaining it away. And there is real danger attached to their exposure.

I want to be able to suspend disbelief about this because there is so much that I enjoy about the book, but somehow I can’t. I have no problem with Leonie in TOS, though that’s arguably less believable because of class and language etc, but I can’t do it in The Masqueraders.

@Azara – People tended to travel more in the 18th and early 19th centuries than we give them credit for. What Heyer understates is the major difficulties of such travel — in Sylvester, or the Wicked Uncle, she makes fun of all of the luggage that gets brought along, missing the fact that when aristocrats travelled to Paris, as they often did, this was for a trip of several weeks or months, necessitating the luggage. See the trips of the Lennoxes or the Shelleys for example.

But Heyer does downplay the various class agitations and changes in the middle class, as well as tensions within London, even when she does acknowledge the class differences at all.

@cass – I have to confess I wasn’t really a fan of the movie, but you are right that the book was excellent.

Heyer does deal with social realities in later books, especially Cousin Kate and Charity Girl, but her early works, for all their focus on historical detail, do tend to be more escapist, as you mention.

@fadeaccompli — And I suspect a related problem with Sir Anthony’s controlling behavior is that he’s doing it to a heroine who genuinely can and has taken care of herself and is pretty experienced in the world — in some ways, I think she knows more about war, scoundrels, and danger than Sir Anthony does. She’s just escaped from the Jacobite Rebellion, for crying out loud.

I’ll be looking more at this in Faro’s Daughter, which also features the controlling hero, but in that case, the heroine really has not been able to control or handle her aunt’s financial problems, making the hero’s desire to control these problems somewhat more palatable. Prudence is doing just fine; Deb really isn’t.

@etv13 — Interesting. The main reason I like A Civil Contract is that it doesn’t pretend that the protagonists could or will fall passionately in love; I found the realistic ending surprisingly satisfying, since it doesn’t lie to the reader, but does provide some happiness for both protagonists.

@Caro — Right, and thanks for putting into words what I couldn’t quite get to.

It’s one thing for brother and sister Prudence and Robin to hide themselves as Peter and Kate. But the final switch sends them right back into being Prudence and Robin — the very identities that were so dangerous at the beginning of the book. The Jacobites were still being hunted, and aristocratc status was not necessarily a protection for anyone.

And you are also right that they are taking a big chance, especially since Prudence is regularly described as unusually tall, and Robin as unusually short. ANd I don’t think we can place much confidence in Letty’s powers of discretion. Eventually she’s going to talk.

I must confess to a fondness for BEAUVALLET, which I reread a couple of years ago (spurred by finding a 25 cent used copy at a rummage sale). Not Heyer’s best by any means, but plenty of silly fun.

I’ll have to reread THE MASQUERADERS. I read it when a teen, but never again, and you make it seem like I must.

—

Rich Horton

Sir Anthony is Not Fat! Large is not Fat. A well built man who might be 6’4″ appears large in an age where even men were slender. I love this novel and I have read it till in tatters.

The element of The Masqueraders that I find most striking is: Prudence’s personality is lifted directly from Shakespeare’s Viola in Twelfth Night. The Further Adventures of Viola of Messaline! It works for me. :-)

(Robin, too, has echoes of Shakepeare’s Sebastian–though Sebastian hasn’t much of a personality. Perhaps we could say instead that Robin is a literary descendent of the actors who played Shakespeare’s female roles.)

The Masqueraders originally took me two tries to get into – and like – because I was confused by both the language and many names by which the gender-switching, pretending characters were called. But, like a maze, once I had the key, I went back and re-read it and it was cunning! I’ve been back many times since then, and the story never palls nor disappoints.

P.S. – I’m surprised that no one has mentioned yet that Beauvallet is the descendant of Simon The Coldheart! For that reason alone, I’d have an affection for Beauvallet! Moreover, I agree with other commenters that it reads in my head as a swashbuckler movie; it is likely to have contributed to making Raphael Sabatini‘s written works more accessible (both comprehensible and enjoyable) to me at about the same time.

Thank you for your reviews of G.Heyer’s books! I’m enjoying them!

Mari, I just found 3 fantastic links on Goodreads. I really think that you’ll want to have a look at them — surprisingly, the first one is especially pertinent. (No, this is NOT spam, and is amazing. Trust me!)

Lady, Your Pardon

0.00 · rating details · 0 ratings · 0 reviews

0.00 · rating details · 0 ratings · 0 reviews

by Georgette Heyer

Magazine, 4 pages : pp. 5, 34-36

Published April 3rd 1937 by The Australian Women’s Weekly

edition language : English

original title : Pharaoh’s Daughter

url : http://trove.nla.gov.au/ndp/del/page/4615411?zoomLevel=3

Incident on the Bath Road

3.00 · rating details · 2 ratings · 1 review

3.00 · rating details · 2 ratings · 1 review

by Georgette Heyer

A very bored Earl, unsure why he bothers going to Bath, zooms along in his chaise until he spots another broken down on the road to Bath. Stopping, the Earl sees the figure of a young man standing there as a means to break the tedium of sameness and so helps the young man continue his trip to Bath.

Magazine, 4 pages : pp. 5, 39, 40, 58

Published May 29th 1937 by The Australian Women’s Weekly

edition language : English

url : http://trove.nla.gov.au/ndp/del/page/4617259?zoomLevel=3

characters : Earl of Reveley, Peter Brown, Lord Jasper Charlton, Henrietta Wetherby

Runaway Match

3.50 · rating details · 2 ratings · 0 reviews

3.50 · rating details · 2 ratings · 0 reviews

by Georgette Heyer

Miss Paradise and Mr. Morley, both 18, have decided to escape the dread fate of having Miss Paradise forced to be married to Sir Roland Sale. They decide, since they had planned to get married to each other anyway, despite the thoughts on the matter of both fathers, to elope.

Magazine, 4 pages : pp. 5, 34-36

Published June 12th 1937 by The Australian Women’s Weekly

edition language : English

url : http://trove.nla.gov.au/ndp/del/page/4614343?zoomLevel=3

characters : Rupert Morley, Bab Paradise, Philip Devereux

And, ha ha ha!, that magazine issue in the first link contains a short story by Raphael Sabatini, too! Niiiicely tying my two (previous) comments together, as well as corroborating my own experience. (The Dragon’s Jaw begins on page 8.) Coincidences are such fun!

I take Prudence’s discomfort with playing a man as coming from her being an inherently open, honest, direct sort of person. Robin can flirt and pursue his romance while disguised as a woman. Pru can’t. Robin can also comfortably sink himself in his role and enjoy playing it to the hilt. Pru, though she does it well, is always very conscious of playing a role. So, I understand her growing more restless, especially as her interest in Sir Anthony becomes more marked.

I suppose that’s also why, while I could imagine Robin making the switch and not being discovered (I imagine him as a very over-the-top dresser in both identities with distinct styles and completely different mannerisms), I imagine Pru as always looking like Pru.

As for Sir Anthony realizing his attraction to Pru ment she was a she not a he: phermones. Amazingly, he not only recognized their effect but had some understanding of the biochemistry. What an amazing, 18th century Heyer’s heroes inhabited.

Gosh, you write well! I’m really enjoying your prose – and your assessments.

I just re-read THE MASQUERADERS after many years, and enjoyed it even more, now – maybe because of the poverty of language in so much recent fiction. I love the way she takes it all the way! I love the series Deadwood for much the same reason. And, yes, it really does stand up under the microscope of current gender politics remarkably well, which is a feat all its own. Unlike her later books, she doesn’t entirely sugar-coat the men’s world that Prudence moves in – she’s got a funny little bit tucked in there about just how much she learns by hanging out with one of the young bucks. And I think she codes that when Pru suggests she is not pure enough to be Lady Fanshawe.

I would point out that Prudence *does* clock Markham with her sword in the first tavern scene – OK, she doesn’t fight a duel, but she sure displays proficiency, and no one in her family is surprised.

I’m always amazed that Heyer never wrote for the stage (nor was adapted for it) – her scenes are always so perfectly wrought, and her dialogue so perfectly timed!

Thanks to Ellen for sending me back to this post *after* I had read a little known Heyer called The Great Roxhythe. It’s an English Civil War noveland I’m reading as many as I can find at the moment. And it is *very* much about male love. Notes below.

Roxhythe is an intimate of Charles II. For him, he acts as a go between. All is well until he acquires a young man, Christopher Dart, to serve as travelling companion and steward. Christopher, whose brother serves William of Orange, is an innocent and an idealist, and he is destroyed by the discovery of his part in Charles II’s machinations.

Frankly, the book is a love story. Written in a more innocent time–perhaps–Christopher declares unabashedly that he loves Roxhythe. Roxhythe never admits of feelings for Christopher but is in turn personally devoted to Charles II. As neither man is married–although Roxhythe has the reputation of a philanderer–I would tentatively suggest that this is a knowing and sympathetic portrayal of the love between two men. There is a gentle nod to the role of Bentink, William of Orange’s friend (Jane Lane in England for Sale will describe him as a pretty creaturem and accuse William of being “a pervert” but there is none of that here) and that William is not a particularly affectionate husband.

One way to read this book is that Christopher is caught in a love triangle; Christopher, Roxhythe (whose first name is David) and Charles.

But the other, which is fascinating, is about loyalty: Christopher’s tragedy is that while he loves and is loyal to Roxhythe, his wider loyalty is to his country, he is a “patriot” and he cannot compromise that. But Roxhythe has no loyalty to country, only to person. While Heyer does not come out and say this, this is one of the fundamental divisions that lay behind the Civil War, a shift from a personal direct loyalty — that Charles I simply expected–to a wider one.

At the end, Roxhythe plots the downfall of Monmouth for Charles, and is at Charles’ deathbed. Beyond it, he is momentarily persecuted by James, who knows that as Roxhythe’s is a personal loyalty, it will not transfer. Roxhythe is assassinated and dies talking of Charles and Christopher, his two great loves. It’s pretty moving.

@ellenkushner Thanks for the kind words!

Heyer apparently did think about writing for the stage, following the example of her contemporary Agatha Christie, but for whatever reason it didn’t work out. She did allow one book, The Reluctant Widow, to be adapted for film, but the result was so terrible that she can be forgiven for never wanting that to happen again. The movie also tanked at the box office so it’s more than understandable that Hollywood didn’t rush to make more adaptations.

I’d think, though, that given the ongoing popularity of other Regency era films — most admittedly based on Jane Austen’s better known works — that somebody will eventually pick up one of the Heyer books and adapt it for film/television.

@farah-sf — The Great Roxhythe is the one Heyer I’ve never read — I’ve never been able to find it for a reasonable price in the States. Last time I checked the only available copies were $50 and up. I assume it will be easily available once the copyright expires and her heirs have to release it into the wild again, but until then…

So this information is fascinating. Thank you. I may be looking at Heyer’s attitude towards gays latter — I tend to think of it as all over the place — so this is a great way to get me thinking.

Sir Antony is not fat! He’s built like a British Rugby player (I can’t remember the name of your team sorry), tall and broad and beefy, ,but not fat. Please!!!!!

And I love that Sir Antony is a man so confident in his heterosexuality that when he finds himself falling in love with “Peter Merriot” he instantly realizes that Peter must be female. It’s not arrogance on his part, it’s just a man who thoroughly knows who he is, and he’s not into guys in that way. I love the diversity of Heyer’s hero’s. The confident heterosexuality of Sir Antony comes straight after the obvious bisexuality of the Duke of Avon, who when he brings home seemingly a 10 year old boy pretending to be 19, his live in, eternally single male “friend” is horrified because he thinks Avon is going to tarnish this young boy’s innocence (presumably by seducing/raping/having sex with him).

The two things I don’t like about the Masqueraders, is the grand old gentleman. I find him incredibly irritating and just not fun. There have been some wonderful “terrible parents who sabotage their kids” in literature (Austen’s Mrs Bennett, the supernatural father in Kate Elliots cold fire trilogy) and for me this guy is not one of them. I also find the language really camp and annoying. The language, even more then the Viscount just doesn’t work for me in this one, and I’m so glad she only did it in this one novel and then abandoned it.