Every year, horror fans are treated to a smattering of books and films that attempt to innovate the genre. Maybe they find a new way to repackage slasher films, like Joss Whedon did in Cabin in the Woods, or they find a new way to present their story, like the “found footage” format of Paranormal Activity. One way to spice up tried and true tropes is to draw on different source material to craft your story.

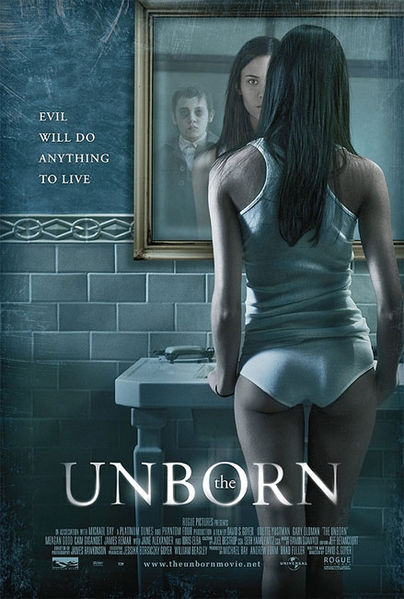

The western horror tradition draws on a shared body of common folklore standardized by western society and pop culture to create its tales of suspense and terror. But, if you want a rich body of folklore chock-full of the strange and supernatural that isn’t as familiar or well understood, you only have to look towards Jewish mythology for new ways of exploring the supernatural. Creative forces in Hollywood have discovered the power of Jewish folklore, as is evident from big budget movies like the recent The Possession and 2009’s The Unborn. But do they get their stories straight? For example, what is a dybbuk and can it really live in a box? And what about a golem? Let’s take a look at some of the denizens of the darkest parts of Jewish tradition to see what goes bump in the night.

It’s important to note that when talking about the supernatural in relation to Jewish tradition, there is some historical context to the way that these stories have evolved. Jewish religious tradition has a very serious belief in the supernatural going back to ancient times: Biblical texts include allusions to kings and prophets speaking to ghosts or dealing with demons, straight through the transition from the Torah (Old Testament) into the later rabbinic texts. In the medieval period, however, an age of “rationalization” arose, leading to a decline in religious belief in ghosts, demons, and the supernatural out of Jewish practice. Still, certain stories persisted down in the folklore and folk practice, emerging in anecdotal tales that later became fodder for great Jewish writers like Isaac Beshever Singer. If one follows the thread of creature-feature talk in Judaism back through the past, though, one finds important distinctions between several kinds of supernatural beings. They break down into three categories: spirits, demons, and weird others.

Spirits: Dybbuks, Ibbur, and Ru’ah Ra’ah

Ghosts or spirits in Jewish folklore break down into a few different types. The most well-known of these is the fiercely misunderstood and misrepresented dybbuk. Recently, the horror film The Possession presented audiences with a story about a little girl who buys a mysterious box at a yard sale and becomes possessed by a demon known as a dybbuk. The movie was meant to be loosely based upon a true account about a box sold on eBay (“the Dybbuk Box”) which was said to contain an evil spirit. Yet both The Possession and the book The Dybbuk Box grossly misrepresent the actual mythology of the dybbuk. A dybbuk is actually a ghost that sticks around after death to possess the body of the living for malevolent purposes. The stories state that it is either a malevolent spirit out to harm an innocent person, or a more neutral spirit out to punish a wicked person for their transgressions. Either way, the defining factor that represent a dybbuk is that they are out to cause harm to their host. They are not demonic, as presented in The Possession, and there is very little indication, traditionally, of dybbuks being attached to locations or items so much as individual people.

Ghosts or spirits in Jewish folklore break down into a few different types. The most well-known of these is the fiercely misunderstood and misrepresented dybbuk. Recently, the horror film The Possession presented audiences with a story about a little girl who buys a mysterious box at a yard sale and becomes possessed by a demon known as a dybbuk. The movie was meant to be loosely based upon a true account about a box sold on eBay (“the Dybbuk Box”) which was said to contain an evil spirit. Yet both The Possession and the book The Dybbuk Box grossly misrepresent the actual mythology of the dybbuk. A dybbuk is actually a ghost that sticks around after death to possess the body of the living for malevolent purposes. The stories state that it is either a malevolent spirit out to harm an innocent person, or a more neutral spirit out to punish a wicked person for their transgressions. Either way, the defining factor that represent a dybbuk is that they are out to cause harm to their host. They are not demonic, as presented in The Possession, and there is very little indication, traditionally, of dybbuks being attached to locations or items so much as individual people.

Another kind of possession talked about in Jewish stories is represented by the dybbuk’s exact opposite, known as an ibbur. The term is used for a spirit that nests or incubates inside a host in an attempt to help the host body along. It is considered a benevolent spirit, usually one which was particularly righteous or holy in their lifetime. These ghostly ride-alongs are said to stick around and possess a person so that they can help them achieve their goals in this life, acting as a wise helper to guide their host toward achieving success. This story got twisted into the horror film The Unborn, in which a spirit incubates in the body of a young woman in an attempt to become reborn again, with some terrifying consequences. Once again, however, the ibbur has never been considered malevolent, like the dybbuk.

Another kind of possession talked about in Jewish stories is represented by the dybbuk’s exact opposite, known as an ibbur. The term is used for a spirit that nests or incubates inside a host in an attempt to help the host body along. It is considered a benevolent spirit, usually one which was particularly righteous or holy in their lifetime. These ghostly ride-alongs are said to stick around and possess a person so that they can help them achieve their goals in this life, acting as a wise helper to guide their host toward achieving success. This story got twisted into the horror film The Unborn, in which a spirit incubates in the body of a young woman in an attempt to become reborn again, with some terrifying consequences. Once again, however, the ibbur has never been considered malevolent, like the dybbuk.

These are the two major concepts of Jewish ghosts that circulate in early stories. In fact, the term for human ghosts didn’t seem to become well defined in Jewish discussion until Rabbi Hayyim Vital coined the term Ru’ah Ra’ah (literally translated into “evil wind”) in the sixteenth century. However, stories of possession in Judaism often get their wires crossed with another element of Jewish tradition and folklore—specifically, stories about demons.

Three Flavors of Evil: Demons in Jewish Myth

If you want to talk about possession, supernatural terror, and general badness in Jewish folklore, you can’t go far without talking about demons. Demons are classified as supernatural beings that have the power to harm people. Jewish tradition has several terms to discuss demons of different sorts, and there are more stories about demons and demonic bedevilment than there seem to be about ghosts. Often times, the definitions for these terms will change from one source to another, causing overlap and confusion which sometimes even overlap into discussion about ghosts. The term Mazzikin, for example, is used in some cases to talk about destructive spirits of the dead, but can also refer to destructive spirits created on the eve of the last day of creation in the biblical story of Genesis. The concept of destructive creatures created at the very end of the Six Days of Creation also finds expression in creatures known as Shedim, which are also alternately called Lillin when they’re described as being the descendants of the mythological figure Lilith. These demons are described as “serpent-like” and are sometimes depicted with human forms with wings, as well. The stories often include descriptions of children being killed in their cradles or some kind of sexualized element, much like traditional succubi or incubi. Then there are Ruhot, formless spirits described in some stories as creatures one could bind into a form to make them speak prophecy or perform a task for the binder.

That last scenario might sound familiar to anyone who has ever heard the story of….

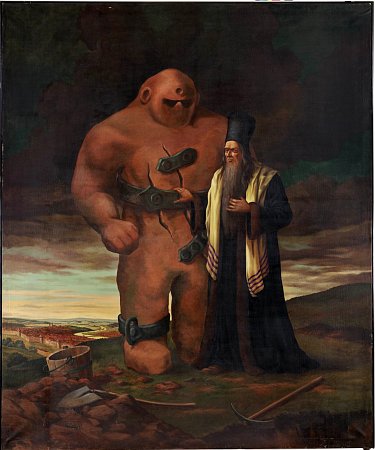

The Golem

The golem ranks right up there with the dybbuk when it comes to being a misrepresented Jewish “monster.” The common conception is that a golem is a man-made monster, sort of like Frankenstein’s creation, which can be made out of clay and given life. The truth of the folk stories is a little more complicated. The golem is described in Jewish tradition as a creature created by a rabbi to serve the Jewish community, often in times of great need. The creature is said to have been made of earth and brought to life by the use of alchemical-like formulas described in holy texts. The creature is not possessed by a spirit or ghost exactly, but driven by the ritual to follow the rabbi’s commands and serve the community until such time as he is not needed. The tale of the Golem of Prague is the most well-known golem story, in which a famous and powerful rabbi saw that his community was being persecuted and created a golem to protect his people. The story caught on to such and extent that the golem has become a staple supernatural creature, featuring in fantasy stories and role-playing games as a popular “monster” when in fact its role was that of guardian.

The golem ranks right up there with the dybbuk when it comes to being a misrepresented Jewish “monster.” The common conception is that a golem is a man-made monster, sort of like Frankenstein’s creation, which can be made out of clay and given life. The truth of the folk stories is a little more complicated. The golem is described in Jewish tradition as a creature created by a rabbi to serve the Jewish community, often in times of great need. The creature is said to have been made of earth and brought to life by the use of alchemical-like formulas described in holy texts. The creature is not possessed by a spirit or ghost exactly, but driven by the ritual to follow the rabbi’s commands and serve the community until such time as he is not needed. The tale of the Golem of Prague is the most well-known golem story, in which a famous and powerful rabbi saw that his community was being persecuted and created a golem to protect his people. The story caught on to such and extent that the golem has become a staple supernatural creature, featuring in fantasy stories and role-playing games as a popular “monster” when in fact its role was that of guardian.

Jewish tradition is chock-full of other kinds of strange and unusual things, like giant sea serpents and gigantic flying creatures, but it’s mainly the dybbuk and the golem and some of the demonic classifications that have made their way into the mainstream popular horror culture. Whether or not they’ll ever be translated correctly, however, relies on whether or not there are writers willing to take the time to offer an authentic representation, rather than another Hollywood rework. In the meantime, some creative license may be taken along the way….

Shoshana Kessock is a comics fan, photographer, game developer, LARPer and all around geek girl. She’s the creator of Phoenix Outlaw Productions and ReImaginedReality.com.

D&D didn’t get golemim utterly wrong; they’re described as guardian constructs that you might encounter protecting a site, not so much a “wandering monster” type of thing. They even harked back to the Golem of Prague story in giving the clay golem a chance to go berserk if it kills.

D&D derivatives like halfassed computer RPGs do things like present golemim as just more random sword-fodder, of course.

The Bible hardly approves of supernaturalism. Even in the story of Saul and the Witch of Ein-Dor (which is what your reference was to, I think), the text is clear that Saul had banished all practitioners of witchcraft. That Saul went so far as to seek one out was symbolic of his fall.

There are stories of Solomon consorting with demons, but those are all Midrashic and apocryphal. And indeed, capturing Asmodeus led to Solomon’s being deposed from his throne and forced to wander Jerusalem as a beggar for a time.

The Pentateuch itself is pretty hardline against ghosts and demons and divinations, as is made clear throughout Leviticus and Deuteronomy. But the Israelites never did live up to the Deuteronomic ideal, which is why we’ve got the Prophets.

In the Islamic countries, yes. In Christendom, not so much. Maimonides and Rabbi Yehudah HaChasid were writing at the same time, you know. And even in the Islamic countries the pendulum began to shift back to mysticism once the Zohar was written, especially after the expulsion from Spain. It was in the wake of the expulsion that the Tzfat circle of mystics formed, and ultimately Lurianic Kabbalah. Which then filtered back into the Ashkenazi world under the influences of Shabsai Tzvi and the Chasidus that rose in his wake.

Well, that’s only THE Golem, the Golem created by the Maharal of Prague. Which is the path that the concept of the Golem took into popular consciousness, but the idea had been around in Jewish folklore for centuries earlier than that (I believe there are testaments to Golem creation in the Talmud). Creating a Golem is basically a matter of imitating the processes used by G-d to animate clay into Adam on the Sixth Day of Creation, which process is described in the Sefer Yetzirah, the Book of Creation, a medieval Kabbalistic work.

I think according to some versions the Maharal’s Golem was animated by Yosef Shida, Joseph the Sheid, who was a sort of “good demon” who used to help the Sages of the Talmud. That’s not the most common version of the story, but the belief in Sheidim was definitely prevalent in Talmudic times, with some tractates describing how best to avoid being attacked by Sheidim at night, or how to summon them.

Personally, I hate when people harp on Jewish demons. Partly because they’ve never been a major component of Jewish religion, only Jewish folklife, and the folklife of the shtetl that gave birth to these supernatural beliefs is dead and obsolete. No Jew nowadays really believes in dybbukim, except maybe the most superstitious and isolated of the Chasidim.

And partly because it’s a sore point that we ever DID have supernatural beliefs. They go against the pure Rationalist tendencies in Judaism, which suit my liking much more, and I hate having to confront both our legacy of mystical beliefs and its modern adherents. I just hate being associated with gullible Polish peasants afraid that every shadow was a demon out to get them. That is not the version of Judaism that has any meaning to me.

Wow what a rude and condescending post. What’s wrong with being a Polish peasant? I’m descended from Polish peasants. They lived in a different culture and that was the belief of their time period, without science and had every right to be afraid of death and that which they couldn’t explain. This was just a light hearted discussion of movies incorporating ancient beliefs, you could have added facts without the unnecessary superiority and snideness about what elements of Judaism you pick and choose to be valid. You may want to realize that Judaism is more about humbleness, kindness and non judgement of other Jews, and not so much “rationality.”