I was interested when I heard there was a book coming out about Snorri Sturluson. As a roleplaying geek, knowing about Norse mythology is obligatory, but while I knew the name Snorri Sturluson in association with the Edda, I didn’t really have any context. That gap was enough for me to put Song of the Vikings on my “long list;” you know, the books you’ll get to, probably this year, but when you feel like it. When I saw that the book’s preface was about J.R.R. Tolkien arguing with C.S. Lewis, I moved it off my long list and to the top of my “short stack.” I was not disappointed; this book quite honestly rocks. Accessible enough to be read as a page turner, but rigorous enough to have some teeth, it hits the non-fiction sweet spot, not so readable as to be one of those trade non-fiction books dismissed as “a long magazine article” but not so academic as to become an impenetrable wall of text. Plus, vikings! Odin! Thor and Loki! Not to mention all the Snorri family drama you could ask for.

Tolkien takes issue with Shakespeare, but mostly because Tolkien’s view of the supernatural is inconsistent with A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Now, I hesitate to criticize the venerable Professor, but I think there is room enough for a heterodox fantasy genre. Then again, I’m not trying to invent a legendarium for England out of whole cloth, either. What I do agree with, however, is that Snorri really ought to be taught more often; he definitely belongs in the same conversation as Homer. Homer really is a better comparison than Shakespeare for Snorri; both filter a vast body of mythology through a single author. There are differences, of course, which are essentially two-fold. The “Homeric Question”—did a real Homer exist? How close do the extant works match what he wrote?—is largely moot in Snorri’s case. He certainly did exist! Of course, Homer was writing from 800 to 500 BCE, while Snorri was alive from 1179 to 1241 CE.

Tolkien takes issue with Shakespeare, but mostly because Tolkien’s view of the supernatural is inconsistent with A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Now, I hesitate to criticize the venerable Professor, but I think there is room enough for a heterodox fantasy genre. Then again, I’m not trying to invent a legendarium for England out of whole cloth, either. What I do agree with, however, is that Snorri really ought to be taught more often; he definitely belongs in the same conversation as Homer. Homer really is a better comparison than Shakespeare for Snorri; both filter a vast body of mythology through a single author. There are differences, of course, which are essentially two-fold. The “Homeric Question”—did a real Homer exist? How close do the extant works match what he wrote?—is largely moot in Snorri’s case. He certainly did exist! Of course, Homer was writing from 800 to 500 BCE, while Snorri was alive from 1179 to 1241 CE.

A larger question is one of original creation. The author of Song of the Vikings, Nancy Marie Brown, deals with some of what she considers Snorri’s contributions in “Seven Norse Myths We Wouldn’t Have Without Snorri” and “Seven Norse Myths We Wouldn’t Have Without Snorri, Part II,” and will continue to examine his works here. (As a brief aside, can I just say how great Tor.com’s readership is? The comments section of both of those posts are filled with a discussion of hermeneutics, which fills my cold black heart with glee.) Personally, I find it incredibly plausible that Snorri added his own flourishes and shaggy dog stories to his works; myth is already a soup of contradictory stories and convoluted canon, just like modern day comic books.

A larger question is one of original creation. The author of Song of the Vikings, Nancy Marie Brown, deals with some of what she considers Snorri’s contributions in “Seven Norse Myths We Wouldn’t Have Without Snorri” and “Seven Norse Myths We Wouldn’t Have Without Snorri, Part II,” and will continue to examine his works here. (As a brief aside, can I just say how great Tor.com’s readership is? The comments section of both of those posts are filled with a discussion of hermeneutics, which fills my cold black heart with glee.) Personally, I find it incredibly plausible that Snorri added his own flourishes and shaggy dog stories to his works; myth is already a soup of contradictory stories and convoluted canon, just like modern day comic books.

The raging fire of Múspelheim and the freezing ice of Niflheim at the heart of the creation myth in the Gylfaginning is a perfect case. Brown argues it more convincingly than I can—both in her post and in Song of the Vikings—but frankly the volcanic nature of Iceland and the tectonic stability of Scandinavia make the point all on their own. Did Snorri add it in, or did he crib from existing Icelandic versions of Norse mythology? I couldn’t tell you, but unless you can cite a source predating Snorri, I’m going to go with him. It is, at the very least, a strong hypothesis, and a falsifiable one, which means it is a good hypothesis, too.

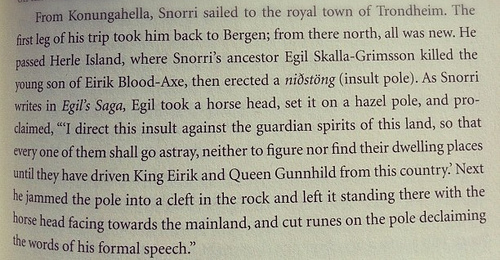

Don’t be distracted by all that, though; if you are you might miss the fact that this book is both hilarious and bad-ass, because…well, because Vikings were both hilarious and bad-ass. For every Kveld-Ulf (the “Evening Wolf,” biggest, baddest dude and likely werewolf) you get an Eyestein Foul-Fart (whose, well, farts were the worst). Or then there is mention of the niðstöng or “insult pole,” where a horse’s head is set on a pole carved with runes insulting the spirits. Both ridiculous and scary, right? That sort of thing shows the dichotomy of Odin, which Snorri and Brown both keep returning to; a god beloved equally of poets and berserkers, a gallows god who finds Loki so funny they become blood brothers.

All of this is sort of talking around what the bulk of the book deals with: the life and times of Snorri Sturluson. Snorri isn’t a brave, bold viking; he belongs in the other camp, with the poets and the cunning tricksters. Born wealthy, his life arcs from there to becoming the “uncrowned king” of Iceland with ambitions to become something more, only to arc back down again to find him dying in his nightshirt, hiding in a basement from assassins, begging them “don’t strike!” Poetry battles, secret plots with kings and dukes, legal malfeasance, infidelity, seduction, illegitimate kids, grudges and feuds, family betrayal, religious condemnation and exaltation…his life story could provide grist for a soap opera mill. Or a Shakespeare play, come to think of it, again with all apologies to the right honorable Tolkien.

Mordicai Knode took that photo of the paragraph about the insult pole because he was so charmed by it when he read it that he just had to. You can follow more of his strange impulse postings on Tumblr and on Twitter

Mordicai Knode is a Macmillan employee.

Is it weird that I want to call hermeneutics debates “hermenautical?”

I am eagerly looking forward to reading this book.

And, just for anyone who hasn’t read it already, I strongly recommend Snorri’s “Egil’s Saga”. Egil Skalla-Grimsson was a classic figure of the Viking Age; by turns explorer, farmer, raider, blacksmith, lawyer, sorcerer and duelist but always, first and last, a killer and a poet. Read how Egil was shipwrecked on the coast of Yorkshire and fell into the hands of his mortal enemy Eirik Blood-Axe, exiled king of Norway. Then saved himself by composing, in one night, and reciting before his enemies the next morning the great praise poem thereafter known as “The Head Ransom”.

2. JohnnyMac

You know, I’ve read bits & snippits of the Eddas, but I’ve never read the whole thing, nor Egil’s Saga for that matter. Got any translation recommendations?

I usually like to read English language literature in the original, but I never felt the need to do so with LOTR, and that preface linked to above is the reason why. I just find the whole story uniquely suited to my native Norwegian language. When I first read it at 13, not only did the names sound vaguely familiar (though I didn’t fully recognise them until I read the Edda poems some years later), but the further into the story I read, the more the language reminded me of the norse sagas. Even the characters resonated with everything I knew of the characters from the sagas. Later (especially after the movies came out) I’ve familiarised myself a bit with the English language version of LOTR, but to me, the Norwegian version will always be the “most authentic”.

Also, I second the recommendation of Egil’s saga. I think it’s fair to say that in Norway and Iceland he is remembered for the poem “Loss of a son” at least as much as for the “Head Ransom”. It was written in grief and despair after he lost his favourite son at sea, and through writing the poem he regained his will to live after having for a while refused nourishment following his son’s death. A great example of “therapeutic writing” if ever there was one.

Mordicai @3, I can’t make any informed recommendations on translations of the Norse sagas. I just picked them up as cheap second hand paperback editions from the Penguin Classics collection. My copy of “Egil’s Saga” lists Hermann Palsson and Paul Edwards as the translators.

Oh and just to whet your appetite for the story a bit further, I will point out that the Kveld-Ulf mentioned in the original post was one of Egil’s grandfathers. Egil’s other grandfather was famous as a berserker. He and Kveld-Ulf were best buddies and used to go out viking together. A werewolf and a berserker BFFs. Now, why don’t they write heartwarming family stories like that nowadays, I ask you?

Innbranna @@.-@, thank you for your very interesting comment on LOTR being suited to Norwegian. I wonder if Tolkien comments on the Norwegian translation anywhere in his collected letters? Must look it up. Your comment about Egil’s great lament “Loss of a son” is also on point. Egil is a fascinating, contradictory character to read about tho not necessarily someone I would want to be within a country mile of in real life. He was rather too dangerous for that.

5. JohnnyMac

Oh, I know the story of Egil, at least a little bit– if I didn’t already, I would have from Song of the Vikings, because Brown talks about it quite a bit. Anyhow, those Penguin Classics are such nice looking volumes, there is a good chance I might just pick that version up, unless I see a pretty “collected purported works of Snorri” book first!

4. Innbranna

As I said to Johnny, I think there is a decent chance of getting a Snorri omnibus, anyhow, right? So hopefully I’ll get the lot of it. Anyhow, reading in translation is interesting, huh? I admit that other than a couple of years of Japanese in college I’m a monoglot. Did you read The Silmarillion in Norweigan, too?

I’m woefully uninformed about translations of Snorre (as he’s called in Norwegian) or the Eddas, I guess it never really occurred to me that these books might be interesting to anyone outside of Scandinavia. Strange, huh? And no, I haven’t read the Silmarillion in Norwegian – in fact I must confess I haven’t read it all! I may be wrong, but I seem to remember it only came out in Norwegian a few years ago. When I read LOTR, reading the English version wasn’t a option since my English wasn’t up to it. Later I’ve found much pleasure in rereading English language classics that I first read in Norwegian as a teenager, and compare the translation to the original. In fact LOTR is the only book I can think of, that I haven’t had the urge to read in the orignal.

7. Innbranna

Well, if you get a kick out of language that is super Scandanavian, The Silmarillion is the book for you, since the lingo is basically lifted off the Kalevala!

7. mordicai

Despite seeing the obvious advantages a properly handled translation into a north German languages (Grumble… Ohlmark… Incompetent… Grumble…), I really would urge you to try the Enlish version as well. Compared to other languages, and not just the awful original Swedish translation, it is something unique in its own language. To put it another way, reading it in our languages enhances the Nordic myths’ influence, while reading it in English really opens one up to the aim of a truly English mythology Tolkien was trying to build up.

8. mordicai

While the lingo is from the same general area, Finnish is quite different from the Nordic Languages, especially Norse. Basically, there are more similarities between Nordic Languages and Persian than between the same and Finnish. However, at least the Swedish translation is quite suberb, mostly because C. Tolkien demanded they’d get a different translator than the abysmal one whom was hired to translate LotR.

And with regards to the book in question, based on the posts the author has made here, I am more and more inclined to check it out. It seems to be a fascinating read, even for one only semi-knowledgeble about the Norse mythology.

@@@@@#5:

I’ve looked through Tolkien’s Letters but come up empty; he doesn’t seem to refer to the Norwegian translation anywhere. (@@@@@copyright holders: Letters needs an ebook edition!)

9. Ipood

I saw her lecture earlier this week; she was great!

#10, thanks for checking on that. I wonder if anyone has done a survey of the various translations of LOTR and Tolkien’s comments on them?

12. JohnnyMac

Right, he’s one of those people uniquely suited to have informed opinions on translation! As a fan of translated works– how great is Borges? So great! But I wish I could read him in the original!– I’m always curious about the subject, & I think the Professor’s thoughts would be a good hook to engage with.

I really enjoyed this one.

What surprised/delighted me most was the inter-textuality of the old sagas and poems. Poets referring to other words/concepts from popular poems both new and old. I liked that a person was well regarded if they could quickly turn an intelligent or humourous phrase.

I also like that this super dense style of writing is then seen going out of vogue and Snorri as standard bearer for the art.

14. Berling’s Beard

He’s the DFW of his time.