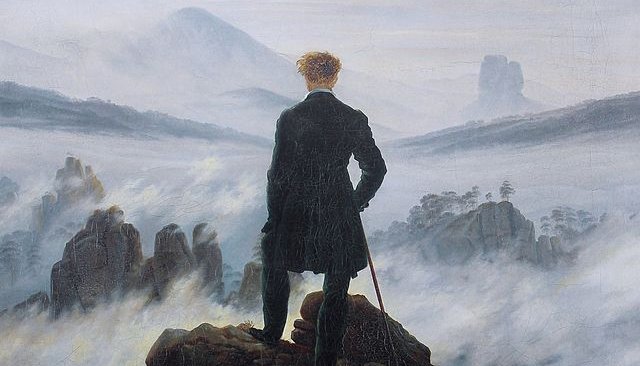

Though I’ve been complaining lately about the stunning visual and thematic sameness of blockbuster films, I do like a lot of them. There’s no denying the emotionally effective manipulation of the BRAAAM! horns, nor the pitter-patter excitement we feel from the ominous, dark stakes they represent. But what of the ubiquitous imagery present in every single blockbuster movie poster? The lone figure standing on a precipice, overwhelmed with…the plot of the movie! Did terribly cynical corporate movie marketing people invent this hacky image? Nope. It comes to us from Caspar David Friedrich’s Wanderer above the Sea of Fog, a sick-ass oil painting from 1818.

Supposedly representing a Kantian state of self-reflection, this famous work is fantastically stirring. However, if this is Kantian (which his what Professor Michael Edward Gorra thinks) then which aspects of Kant’s philosophy are we dealing with? Is our lone ominous figure—whether he be from Inception or Star Trek Into Darkness—contemplating the Critique of Pure Reason? Or perhaps reflecting on The Beautiful & The Sublime? Well, if we do a little bit of time travel cross-application, I think if the lone figure in all the blockbuster movie versions of Wanderer above the Sea of Fog is meditating on anything written by Immanuel Kant, it’s probably the “categorical imperative,” found in his book, The Groundwork for the Metaphysics of Morals.

Briefly, the categorical imperative states: “Act only according to the maxim whereby you can, at the same time, will that it should become a universal law.” Whoa! That certainly describes the extreme nature of tons of the protagonists/antagonists of these various films. From Bane and Batman in The Dark Knight Rises to everyone in Inception, the idea of finding a universal truth and then applying it (sometimes forcefully) onto everyone seems to be exactly what’s at the core of all these movies.

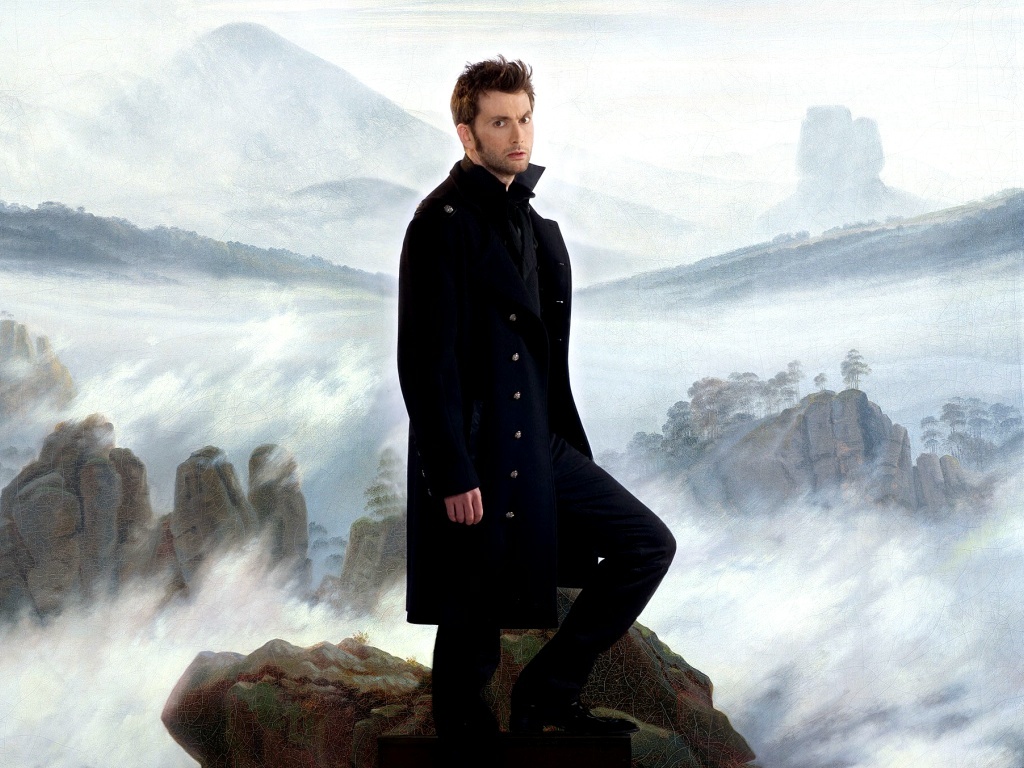

Even reboots of classic characters don’t seem immune to the categorical assertion of the Wanderer above the Sea of Fog pose. When you check out Cumberbatch’s Sherlock, and David Tennant’s Hamlet it becomes fairly clear that the ominous character on a search for a universal truth might the most pervasively inescapable pop-storytelling theme of all. I mean, it’s not like Sherlock Holmes or Hamlet are philistines when it comes to the subjects of truth or universal truth. That’s kind of their jam.

What’s that you say? Maybe this image persists because it just looks cool? I would buy that, but only to a point. Aesthetics aren’t the same as superficiality. Whether we’re aware of it or not, this striking image evokes something, the same way the BRAAAM horns do. In all honesty, if it’s not strictly Kantian (which we’ll never really know, just because Friedrich and Kant are both German, I mean, whatever) then the image might have such powerful resonance simply because it depicts BIG STAKES. Or to put it another way: it implies the theme of inevitable change. The guy in the Friedrich painting has to come down from there at some point. The guy in the Battleship poster is going to have to do something about that alien thing in the water. Inception is going to need to figure out what the word “real” even means.

These decisions are what make big plots exciting. And the moment right before or right after those big decisions are made is when the audience—whether in a movie theater or art gallery—actually really cares and connects.

But the big question though still remains: Does Shinzon count?

(Thanks to cheezburger.com for bringing this to everyone’s attention. Also, Wikipedia.)

Ryan Britt is a staff writer for Tor.com.

Do most of the current artists have classical training? Is that why we see the same images? Or are they reproducing a meme that they don’t know the history of? Interesting essay….

Fantastic post! Thanks for sharing it. I had no idea. For another example, check out the much-maligned movie, “John Carter.” You can see it here:

http://robotgeekscultcinema.blogspot.com/2012/03/review-john-carter.html

Even Tor bookcovers!

http://www.tor.com/blogs/2013/01/cover-revealed-for-brandon-sandersons-steelheart

Or perhaps he just finished reading The Critique of Pure Reason and is thinking “WTF did I just read?”

Good illustrators have knowledge of all sorts of art but I’d guess these movie posters/promotional images look similar not because the artists are referencing a 19th century painting but because marketing decision makers say “We want an image like this” and then show the illustrator a print of some other movie/show poster.

Interesting article.

And the actual image has been used many, many, many times. Here are four:

http://palimpsest.org.uk/forum/showpost.php?p=127001&postcount=122

Someone once told me that the 219th century painter John Martin (a local lad!) inspired the look of Hollywood big explosions:

Not sure if this link will work.

And that would be 19th century, not 219th. Doh!

Friedrich was the leading artist of German Romanticism; the usual gloss on his art is that it is indeed about the sublime, that is, the experience of the unknowable. For Friedrich that had religious or mystic undertones. There are fun discussions of this and other Friedrich paintings in Landscape and Memory, by Simon Schama.

Big-R Romantic tropes and imagery have been very influential. It isn’t very surprising to see this pose transmuted into generic one-man-against-a-world-he-didn’t-make imagery.

The Dark Knight Rises one doesn’t really fit in there. It’s an imagine of looking up into the sky through the wreckage of skycrapers making the Bat symbol. No person in sight.

Ryan, When I first read the words “sick-ass,” I thought it was something disparaging. But in context, it appears that you used it as a compliment. I think.

Please provide a translation for this befuddled old guy…

@ThePendragon: I was wondering about that too. Do you think it is a test to see if we’re paying attention?

This style of composition is known as “Rückenfigur” and actually pre-dates Friedrich, although he is definitely is the most popular example of it and of the specific “halted traveller” motif. One could say people are ripping off this particular painting, but it’s a compositional style that has been used in paintings, movies and photography throughout history.

Yes! Sick-ass is good!

I suppose the link between Friedrich’s romantic painting and Kant is the then new concept of individuality for which both (Kant and romanticism) provide key thoughts. In the history of ideas around 1800 is somewhat of a turning point regarding the concept people have about themselves and there position in the world, and both Kant’s contribution to the Enlightement’s concept of being human and the romanticists (at least the German ones, don’t know about others) with their notion of individuality, genius and self-centered introspection are especially important for this development.

And as individuality, the central focus on one human in a wider, large and not entirely conceivable or controlable world (nature! destruction! largeness! chaos!) still is a very important thing for many films — obviously it is the first step to the notion of the hero — it makes sense that Friedrich’s mode of visualisation of those concepts is still used today.

Not that I see Kant as being much of a friend of women, but is it possible for a woman to inhabit this ‘heroic’ pose, do you think?

It seems (to me) very much a meme of ‘hegemonic masculinity’ and for that reason a little barf-worthy, if you’ll excuse my cynicism. If only men were a little better about saving the day in ‘real life’, rather than just in the movies, then I might take more comfort from it. Under the current gender order they seem a little more practiced at destruction rather than salvation…

It is kind of like a visual version of those trailers with the overblown narration, “In a world where a man faces dangers greater than anything he ever imagined…”

In the picture of Cumberbatch/Sherlock he is stood on, a Tor!

(http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dartmoor#Tors).

And to be fair, if you go wandering on Dartmoor, the compulsion to go stand on top of one is pretty hard to resist, it’s usually bloody windy though.

Not just Hamlet – also Macbeth

http://www.macbethwestend.com/

You forgot two posters that use villains or antiheros in this pose: Joker on The Dark Knight poster and Rorsharch on Watchman’s.

Your article title is a bit link baity because it does not help explain blockbuster posters like Star Wars, Titanic, Avatar, E.T., Casablanca, Gone with the Wind – just to name a few. But hey, we have to make a living.

I do like the similarity you draw between a 19th century painting and the other posters. I’m sure you could find a 19th century painting of a couple that’s archetypal to all romantic comedies, too.

I think your discussion of Kant was a bit heavy handed and pretentious, but that’s really my problem for majoring in philosophy. I don’t think Kant meant “will” in a Nietzschean sense.

Please don’t be a slave to getting more hits.

See also, Michael Douglas on the VHS cover of Falling Down.

“just because Friedrich and Kant are both German, I mean, whatever”

And Hans Zimmer, inventor of the BRAAAM, is German too. Coinky-dink?

Great article. Adds to my belief (or hope?) that postmodernism is dead and we are currently in the midst of a Romanticist revival.

Let’s call it ‘Neo-Romanticism’ for the sake of argument – as opposed to ‘New Romantic’ (different thing altogether).

I love this post! That is all. I can’t believe the Tennant photo isn’t photoshopped (or is it?). And Sherlock on top of the boulder? Priceless. I adore the Friedrich, though. Imperatively.

Yrrw but is it possible for a woman to inhabit this ‘heroic’ pose, do you think?

— have you looked at many fantasy/SF covers lately?

>It seems (to me) very much a meme of ‘hegemonic masculinity’

— actually it’s a classic Romantic image of lonely rebellion. This was the same period as Mary Wollstonecraft.

Not an accident.

Without Enlightenment/Romantic individualism, feminism in particular isn’t even imaginable.

BTW, when everything you see starts to look like a nail, it’s a sign you’re viewing the world through hammer-shaped glasses, to coin a phrase.

>Under the current gender order

— which one? 1818, which is when the painting dates from, or now? Bit of a difference.

@@@@@mariesdaughter

Most professional artists have had some sort of schooling, and that means Art History class. If you have a good understanding of art history you’ll realize that this kind of homage pops up a lot in all kinds of art media.

A lot of it is just geniune love for the artists, and sometimes it’s just a little inside joke to include these kinds of references.

In the case of Wanderer above the Sea Fog, it’s just so darn effective. You don’t really have to think hard to get the feeling of awe in this one.

Calling BS on this one.

Lone figure contemplates surroundings was never original or deep.

I agree with Laransb — these images evoke questions about the individual’s relationship with an overwhelming natural/supernatural world. There is a tension between the respective power of the setting and that of the central figure represented which makes the relative scale of each important for how we view the role of the hero in these scenarios.

That’s not all, folks!