If you read comics long enough, or with any kind of sustained attention, you’ll notice that some series start off strong, with clear, powerful opening issues that define everything that will follow. Others don’t grow into themselves until a few months, or a few years, into the run, when the creative team kicks away the specter of influence and begins to tell their own stories.

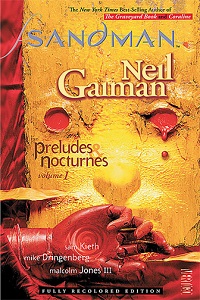

Sandman, Neil Gaiman’s most prominent comic book creation, doesn’t become itself until issue #8, the final chapter in the Preludes and Nocturnes collected edition.

Readers will find plenty to enjoy in the opening half-year of stories, but the Alan Moore influence is strong and anyone who goes back and rereads Moore’s legendary Swamp Thing run (as I, of course, have done, in public, not-so-long ago) will see the template Gaiman follows for his opening Sandman story arc: the ponderous DC-mystical-rich questing, an old corporate property revised for a new age, hitherto untold mysteries of the past, superheroes as creepily-colorful background characters, and a deep literary heft with words and sentences that are far more lyrical than the usual mainstream American comic book fare.

That is the essence, or at least the stereotype, of what would later be Vertigo Comics, DC’s “Comics on the Edge” imprint masterminded by Karen Berger, the editor who shepherded much of Moore’s Swamp Thing and all of Gaiman’s Sandman. But before Vertigo was Vertigo, it was Berger’s corner of the DCU, and Gaiman was the first of the post-Moore writers to mimic the best bits of Moore and then build those pieces into something much more personal. It didn’t take long for Gaiman to weave his own interests and philosophies into Sandman—he does it from the very start—but it takes him seven issues to run through the Moore tropes sufficiently to break free from them enough that they become narrative tools instead of clearly-defined rails. Or, if we’re putting it in terms of sentience, Sandman #8, a story titled “The Sound of Her Wings” is where Gaiman’s Sandman comic comes alive. Ironic, really, since it’s a story mostly about death. But that’s Neil Gaiman for you.

Issues #1-7 aren’t bad comics, not even close, but it is shocking to go back to these early issues after considering Sandman as a whole, and to realize how much of the series comes into focus from issue to issue. It says it’s Sandman, those Dave McKean bookshelf/collage covers are there from the launch, and the world of Morpheus and the implied mythology of the Endless emerges in front of us, but the way Sandman feels as a whole and the way these first half-dozen-or-so issues read creates an unsettling discord.

Actually—and quite helpfully—as we look back on Sandman from over two decades removed, the weird unevenness of the opening story arc helps keep it from stumbling into the cage into which some critics would like to trap it. Because of the popularity of the series in the early 1990s, and Gaiman’s literary and cinematic ascendancy ever since, Sandman sometimes seems—or sometimes is criticized for being—frozen in time, a relic of early Hot-Topic-style Goth, a frilly-but-leather-clad confection of saccharine Romance, as dated as the fashions the Vampire: The Masquerade players would wear while conspiring against their fellow Kindred.

But while that may be the reputation of the comic in some circles, and while some of the merchandising of the time may have helped to perpetuate that notion—there was a Sandman-heavy Vertigo Tarot deck for sale back then, let’s not forget—the truth of the series is that of a neverending cycle of stories, set in distinct times, but with a playfulness of generation, and of fashion. Yes, there is something distinctly 1990ish about some of the issues, but there are just as many that flash back, hundreds of years into the past, or into the depths of legend and myth.

Plus, reading the first few issues, there’s this: Sam Kieth.

I’ve read the entire run of Sandman at least three times before. Once when it first came out, in single issues (though I will note that I skipped the purchase of issues #2-3 originally, back in my teenage years, and then had to track them down when I picked up issue #4 and realized that, yes, this was indeed a series worth keeping up with), the second time when I started buying the trade paperback collections during college and just after, so I could let my then-girlfriend-and-now-my-wife get caught up on the series, the third time after moving into our first house, when I was organizing my new bookshelves and couldn’t resist going back through the series after seeing all the volumes neatly arranged in front of me. And now this time, a decade after reread number three.

Perhaps it’s that ten-year gap, but I forgot how much the early issues look definitively like Sam Kieth comics, and not at all like the Mike Dringenberg comics they would soon become. Dringenberg, the original inker of the series who would take over the penciling job by the end of the first arc, is the artist most closely associated—in my mind at least—with defining the look of Sandman. Dringenberg drew the DC house ads warning us that a new Sandman was coming, complete with an ominous T. S. Eliot quote. He drew the images that adorned the Sandman t-shirt and poster (and yes, I owned both, once upon a time). He drew “The Sound of Her Wings.”

And yet, in issues #1-2, he is barely present, occasionally visible in some of his scratchy cross-hatching, but that’s about it. In issue #3, he seems to redraw a few Sam Kieth panels, clumsily, because his quasi-realistic, angular rendering doesn’t match Kieth’s soft, hauntingly-Seussical figure drawings at all. But a few issues later, Dringenberg takes over and brands the series as his own. The interiors match the marketing, by then.

Though this is a Neil Gaiman-centric reread, and as I go through the various Sandman arcs and collections, I will undoubtedly talk more about the writer than any of his artistic collaborators, I’ll point out, here and now, as we’re just digging into this stuff, that I don’t think Sandman would have been the phenomenon it became if Sam Kieth had stayed on as artist through its first year. It became much sexier, much more in tune with its time—hence the occasional jab at the series seeming “dated,” though I don’t agree—when Dringenberg began providing the pencil art. His was a much more approachable style, with gender-line-defying appeal (I know I was far from the only male comic book reader to share Sandman as a gateway to comics with a girl I was interested in).

In retrospect, I prefer the Kieth pages more than the Dringenberg ones. Kieth—who went on to take his distinctive style to Image Comics where he created the bizarre, also-dreamlike series The Maxx, which later became an after-hours MTV animated series—is a much more adventurous artist. No one in comics draws like him.

But had he remained on Sandman, and had he drawn “The Sound of Her Wings” in issue #8, it would not have resonated with audiences the same way. Kieth’s version would have been fascinating, surely, but it would also have been more grotesquely comical instead of hauntingly beautiful. Kieth reportedly stepped away from the series before that time because he felt like Dringenberg was the superior illustrator, and he was embarrassed to be unable to live up to what Gaiman envisioned for the series. It was the right move for everyone involved, ultimately, but I still find Kieth’s early work on this series amazingly charming. Really, his biggest weakness, as a collaborator of Neil Gaiman’s on a series like Sandman, was that he didn’t draw his characters to look like Neil Gaiman. Dringenberg did. His characters look like they hang out in the same book shops as Gaiman himself, and when the writer is as much of a star of the comic as the characters are, it’s important that they look like they inhabit the same world, real or fictional.

That synchronicity would happen later. When the series starts, it’s deeply entrenched in the Gothic, rather than the Goth.

Neil Gaiman begins his epic with a double-sized opening issue. We meet Roderick Burgess, would-be-Magus, who attempts to capture and control Death, but misses the mark. Notably, Dream (aka Morpheus, aka the title character, though he’s rarely, if ever, called “Sandman” in the series), remains silently imprisoned for most of the first issue. A bold move from Gaiman, and while he may have learned at the foot of Moore (or from the Moore comics at his feet), imprisoning his protagonist for 70 years is even more ambitiously daring than the death-and-resurrection-of-the-hero game Moore liked to use. It’s one thing to kill off your main character to symbolically bring him or her back in a purified form, but it’s another thing to imprison your main character for a lifetime and then give your hero a chance to escape and try to reclaim what was once his.

Gaiman uses the long imprisonment of Morpheus as the engine for practically the entire series. Morpheus was the cork holding the dream-stuff inside the bottle, and he spends several story arcs worth of his time trying to clean up the mess others left behind when he wasn’t there to stop it. More importantly, perhaps, Gaiman shows us what it’s like when our hero isn’t there. I mean, he’s on the page, but he’s impotent, shackled. The loss of Dream means the loss, to a large degree, of story. And if Sandman is about anything, and it is, it’s about the power of story. This whole series is like the pilgrims headed to Canterbury, taking turns telling their tales. It’s Scheherazade weaving fictions to stay alive. It’s Neil Gaiman, building a structure through which he can tell a multitude of stories from different times and different places, but with the advantage of a single narrative thrust to tie it all together.

So we get, in the second issue, DC’s Cain and Abel, guardians of the House of Mystery and the House of Secrets. Alan Moore had used them—and added a new dimension to their previous roles as mere hosts to now-dead anthology comics—in Swamp Thing, and Gaiman picks up from where Moore left off. Morpheus is, in comic book terms, an heir to the tradition of the DC Cain and Abel. He has much more in common with them than he does the other costumed characters who have bopped around the DCU calling themselves “Sandman.” In fact, as Gaiman tells us in the first story arc, the Golden Age Sandman and the Bronze Age Sandman where created because of the absence of the real deal. Morpheus was away, and others, unknowingly picked up tiny pieces of his role.

Really, though, Dream is a mechanism through which Gaiman can explore all manner of stories. But what Gaiman does well is make Morpheus just human enough—for a god—to make the reader care about him, and then walks the line between Morpheus-centric and storytelling-centric arcs with just enough dexterity that the reader feels like Sandman is more than just an anthology series and yet more than a supernatural adventure story. The relationship between both, and Gaiman’s deep well of literary allusions (enough to warrant an annotated edition of the series) give the series its fullness.

Issues #3-4 take Dream to Alan Moore’s own John Constantine, and the seedy underbelly of magic-as-a-drug, and then directly to Hell where Lucifer and the other members of the demonic Triumvirate rule. Dream wins back what belongs to him, and standing in front of the unyielding legions of the underworld, gives the speech that defines the mission statement of this series, and the mission statement of fiction itself, bound up, like the myth of Pandora, in the power of hope: “Ask yourselves, all of you…What power would Hell have if those here imprisoned were not able to dream of Heaven?”

The rest of the opening story arc, pre-“Sound of Her Wings,” is Gaiman playing most closely off the strings of Alan Moore’s Swamp Thing. What Moore did with Woodrue, the Floronic Man, Gaiman does with John Dee, Doctor Destiny. It’s as if Gaiman laid the Moore template over the Morpheus story and asked himself, “if the Floronic Man is the corruption of the Green, unleashed on humanity, what is the equivalent in the world of Dream?” The answer came in the form of an old Justice League villain, Doctor Destiny, who in the Silver Age comics used the high-tech power of the Materioptikon to create reality out of dreams. In Gaiman’s telling of events, the monstrous and physically decrepit Dee enacts a nightmare scenario inside a diner, and his confrontation with the true power of Dream is short-lived, but not before savaging a group of innocent victims.

Sandman is never as much a horror comic as it is in issues #5-7, where the Alan Moore Swamp Thing influence is strongest. It is sometimes a horror comic after that, but much more of a dark fantasy. Gaiman always had too much Lord Dunsany in him to stay in the world of hyper-violent horror for long.

And to signify that break—to provide an epilogue for Gaiman’s opening story arc and to provide a prologue of what’s to come—Gaiman (now with Sandman-marketing-defining artist Mike Dringenberg on every page) gives us issue #8, “The Sound of Her Wings,” which I’ve mentioned half a dozen times already without ever talking about directly.

It’s a story so pivotal that it showed up in both the first and second Sandman trade paperbacks in their original printings, and it still shows up on multiple occasions, like in both Absolute Sandman Vol. 1 and Absolute Death, as unlikely as it is that someone who owns the latter would not already own the former.

“The Sound of Her Wings,” for all that I’ve built it up, may not read particularly well in isolation. If you were to read it on its own, and no other Sandman issue ever, you might be well-justified in writing off the entire series as the “frilly-but-leather-clad confection of saccharine Romance” that I alluded to earlier. The story is a relatively simple one, like something that might have appeared on an old Twilight Zone episode, where it turns out that the cute, spunky girl in the park is actually Death herself, and she goes about her daily routine with a sense of style, compassion, and verve.

But it’s a refreshing single issue after everything that preceded it, opening up the series to a kind of bright energy that’s missing throughout its entire, grim-but-powerful first arc. Gaiman’s characterization of Death—and Dringenberg’s visual depiction of her—provides a much-needed foil for Dream. Through his experiences walking with her, he remembers who he is and what he needs to do, and he allows himself to feel the hope and potential for joy that he, a few issues earlier, used as a weapon against the demonic hordes.

Dream had been imprisoned for 70 years, and escaped into a series of increasingly horrific situations. To give him this issue to reflect and banter with his sister and think about the future, well, it amplifies the power of this single issue. And it does something else too: it confronts life and death and reminds us of the potency of Dream, not just within this series, but as a concept. And it doesn’t do it laboriously, but with a light touch and charisma, stemming from the ankh-sporting youthful Death.

Gaiman may not have exactly followed Alan Moore’s superhero-death-and-rebirth formula in the first year of Sandman, but Morpheus descended into the depths of Hell and then faced a hell-on-Earth in his confrontations that followed. “The Sound of Her Wings” is the cleansing rebirth for the character. A fresh start, with wounds still unhealed but no longer bleeding. It was a chance to set his protagonist on the stage, apart from Morpheus’s role as agent or reagent, and to ask the audience if they cared to follow him.

They did. We did.

Even twenty-something years later.

NEXT: The Doll’s House

Tim Callahan has been a Sandman reader since the very beginning, and though he no longer has the t-shirt to prove it, he has pictures of himself wearing that t-shirt buried somewhere in his aunt’s basement.

Ouch. I resemble that remark…get off my lawn! Back in my day, we had to pin our OWN safety pins onto our clothes…none of yer fancy Hot Tropics of whatever you call it…and I had to walk three miles uphill in black pointy witchboots to get a decent cup of coffee…*grumble*

Ah, Sandman. I heard it was good, read ‘Preludes and Nocturnes’ and it turned me off the story completely.

The Cain and Able story disturbed me, then the Dr. Destiny story made me decide that if I wanted torture porn… well, I didn’t want torture porn so I stopped right there.

Never got to ‘The sound of her Wings’ so maybe I missed out. If I ever find the book again I’ll read the last one to see if it was any better.

How exciting. Though I showed up on the scene way too late to comment on any of the Alan Moore stories I own, I happen to have a never-before-opened copy of Preludes & Nocturnes I picked up a while ago after having been enamoured by Mike Carey’s Lucifer. I’ll give it a read tonight and I’ll go through the series for the first time while you read it.

Issues #1-7 aren’t bad comics, not even close, but it is shocking to go back to these early issues after considering Sandman as a whole, and to realize how much of the series comes into focus from issue to issue.

I liked reading those issues. They stirred my imagination. We were exposed to some of the Gaiman sense of irony that Neil showed us, earlier, in collaboration with Terry Pratchett on Good Omens. He also began the process, in those issues, of reclaiming some of DC’s supernatural and magic user characters.

Agree that something new started happening with “The Sound of Her Wings” in #8. That’s when we got to meet Morpheus’ sister, Death.

I absolutely fell in love with Gaiman’s Death in “The Sound of Her Wings”. It brings that the powerful dark grim opening arc to an incredible conclusion and as you say sets the tone for so much of the rest of the series. I was lucky and read the entire series at a friends house who had the bound set and I actually picked up one of the others first then went back and started from the beginning.

But if you have read the first 7 issues “The Sound of Her Wings” is an amazing world changing issue.

Also as you say it never gets as dark again as the Dr Destiny issues. You would think that issues that feature The Corinthian would be darker but oddly they aren’t, by that point you understand him better. And I will eagerly await your reread. Just a couple of months ago I bought all the bound sets for my iPad and downloaded and reread them. So I just finished a reread.

I had gotten away from comics as a boy and growing up and older, so when I came back to them it was to Sandman and skipped over Moore, only going back to him later.

But, I must say and in all honesty, after reading these 2 greats I simply cannot read practically any other comics before something like the late 90s, at the earliest. Anything before that point is simply too bubble gum and silliness.

Love this/

Megaduck, alas, you stopped right at the darkest worst horror-est part of the series – apologies. Try issue 8. Then try The Doll’s House. I think you’ll want to VROOOOM through to the end (and beyond), afterwards. Other rereads I’ve seen (markreads’, for example) note afterwards that issue 7 should probably come with a warning label telling you not to quit because of it, it’s as bad as it gets…

–Dave

Megaduck:

Interestingly, in the UK the first Sandman trade edition was The Doll’s House which started with ‘Sound of Her Wings’ and featured an introduction by Gaiman which ran quickly through the first stories. That was my introduction and I assume that the publishers (Titan Books) correctly realised that many potential readers would be put off by the heavy horror and the strong Moore influence*.

In my opinion, it’s definately worth your trying again, this time starting with The Doll’s House.

*One sequence almost exactly mirrors a Swamp Thing sequence as a series of horrific events across the US is shown and a character who always watches (Destiny in Sandman, the Watcher [?] in Swamp Thing) is ‘for the first time’ tempted to look away

I had never thought of this relation between Sadman and Alan Moore, thank you for that.

I don’ t agree with the first 7 issues being unfocused or weak. I think it’s one of the best openings any series had and I think it has a very clear purpose: to introduce this whole new world to us. It says “Although you might see Batman over here, this is *not* a superhero story”. It shows how the world would be bleak devoid of dreams and how nightmares can take shape. I was shocked when I read the Dr. Destiny story and thought “they can do *that* in comics?”, and this was good, because it broaded so much what I thought could be written in comics. Comics was no longer Superman and Spiderman.

http://www.tor.com/blogs/2009/09/re-reading-lemgsandmanlemg-issue-1-qthe-sleep-of-the-justq

Thanks for this. I’m very glad we are doing a Sandman re-read here (having just lent “Doll’s House” to a friend). It was a pity that Teresa’s re-read from a few years ago (linked above) didn’t work out in the end as there is plenty of crunchy goodness to squee over.

“Really, his biggest weakness, as a collaborator of Neil Gaiman’s on a series like Sandman, was that he didn’t draw his characters to look like Neil Gaiman.”

That’s unfair to Sam Kieth. At the time Gaiman was an up-and-coming comics writer, hardly the mega-star he is now. And I do not think you can blame artists for not drawing characters to look like their creators. What next? All Powers characters should look like Brian Michael Bendis? All Peanuts characters should look like Charles Schultz?

Re: reading order.

IMO, the “Doll’s House” TPB is the best starting point. I had looked at the first issue, but decided it wasn’t for me as it read too much like a horror (and “Preludes & Nocturnes” is horrific). It wasn’t until I read the “Doll’s House” TPB which starts with “The Sound of Her Wings” that I was converted.

Probably not coincidentally, “The Doll’s House” was the first published

collection of Sandman comics, despite not being first chronologically. I

didn’t understand why at the time (and yes, I sure wish I still had that

first edition!), but I now suspect this was a deliberate choice by DC to

play to/not scare off the rapidly growing female fan base.

I was very lucky, I succumbed to Dave McKean’s gorgeous covers – boy, did those stand out amongst the superhero comics – with issue 8. I don’t think I would have given issues 6 or 7 half a chance, otherwise. Having said that, I still feel the books should be read in order, that you need the knowledge of what Dream has gone through to understand the

decisions he makes later. When I recommend the books to people, I tend to warn them that it gets pretty icky for a bit, but that it is worth it.

(Tim, not to play who-has-the-most-t-shirts, but I met my husband-to-be in line for a Gaiman signing. He signed extra books for us when we gave him a wedding invitation three years later.)

The Doll’s House was not only the first collection of Sandman comics, but one of the first collections of comics ever printed. It could be said to be largely responsible for the concept collected editions of comics – the only way to read comics, in my opinion – being as widespread as it is today.

Hard to imagine there was a time when an A-list comic book wouldn’t be assumed to be collected in its entireity at a rate keeping up with its monthly publication, but there you go: The reason Preludes & Nocturnes took a while to be rereleased in collected form was that no one thought it was good enough to deserve that treatment.

Now, Sandman is hands down my favorite thing in the history of fiction, but I’ll admit the first part is rough and rushed, clearly made by a team figuring out how to do their various jobs as they go along. Though to their credit they do manage to get their ducks in a row before that first outing is even over, ending on an high note. An unearthly, ethereal note that rings true still here, now, in another millenium.

What I take away from The Sound of her Wings isn’t the poetry or clarity of the narrative or the tight, glamorous design or the fashionable sensibilities, the wonder of Death or even the deep and beliveable psychology of the characters here emerging, but rather the sheer mundanity of what happens. I’m an only child, but I’d like to think the story here captures the essense of daily life with siblings, from the extremely casual greeting (after a seventy year separation, even) to the attempts at communication to education to exhaustion and ultimately unconditional reconcoliation.

As unlikely as a comic book without men in tights punching each other in the face, here are these beings – he might rule over the realm where gods are born and die, she may be carrying the most important thing in the entire universe around her neck – who have an ordinary day and ordinary conversations about their ordinary troubles with their family and jobs.

Which, like everything else, when you look closely enough and care about it enough, becomes magic.

SarahKitty @14:

“Doll’s House” works brilliantly to get the reader engaged, what with the killer introduction Gaiman wrote for it. It made a virtue of coming in at the middle of a story (and even if we had started with P&N we wouldn’t have got to the beginning of Morpheus’ story anyway), and with a more settled look than the issues that made up “Preludes & Nocturnes”, had a better chance of hooking the reader than P&N.

I would recommend reading Doll’s House first, then Preludes & Nocturnes, and from there, the rest in original publication order.

Tim, how is the re-read going to proceed; do you have a rough schedule? I invested in the giant expensive HC collections, but didn’t actually crack them yet, and this will be a good prompt, though inconveniently coinciding with Tournament of Books season:

http://www.themorningnews.org/article/announcing-the-2013-tournament-of-books

just slugged through Sandman myself.

Completely average, with below average art, on the whole.

Far more inventive comics about stories, myth, cycles, etc.

Now I’m drooling over an Annotated Sandman.

I know there was one line, I think from Doll’s House, that was straight out of the Aeneid, which I had just been translating before I read Sandman for the first time. I love it when I have a moment where I recognize what amazing research Neil Gaiman has done for his stories.

GirlDetective: This will be a 15-part series, going through the trades in the order of their original serialization, with a few posts on the Gaiman-written spin-offs (like Death: The High Cost of Living, etc.)

I assume they will be going live on the Tor site each Wednesday, but I’m not sure about that.

RE: the Swamp Thing connection: Dream’s raven Matthew is Matt Cable from Swamp Thing.

I love the way The Sandman tells a lot about who we are

based on what we understood about the work.

Probably because of that, It represents to me the pinnacle of the comics’ medium.

A Hope in Hell remains to me the story that makes everything worth while.

Long live Preludes & Nocturnes as the first, undisputed read.

Congratulations, #18, for being part of a minority I will never be a part of.

It takes a great deal of intelligence to deal with some issues (heh) of Neil Gaiman’s story,

and honestly for the better as you have shown with your insights,

not everyone has the time to do so. This is, if I got it right from Morpheus and Death,

what makes some things special.

Fantastic article, Mr. Callahan.

Saludos desde Argentina.