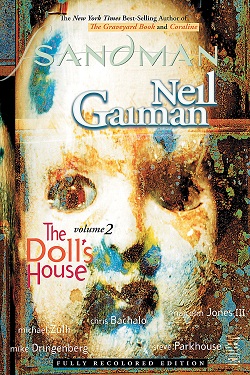

I mentioned last time that “The Sound of Her Wings” was originally reprinted in both the first and second Sandman trade paperbacks, and that’s true, and it is the story in which the series fully comes to life. But there’s another reason why the original trade of The Doll’s House began with that story: The Doll’s House, collecting the second story arc of the series, was actually the first collection printed.

In the days when not everything from DC Comics was guaranteed a collected edition, someone at DC clearly thought that the first half-year of single issues wouldn’t be as appealing to the bookstore market as the stories that made up “The Doll’s House” arc. It wasn’t until later that Preludes and Nocturnes came into print, and that’s when “The Sound of Her Wings” slid back as an epilogue to volume 1, rather than a prologue to (what would become) volume 2.

Because, as it stands now, The Doll’s House collection has a prologue of its own, in Sandman #9, “Tales in the Sand.”

“Tales in the Sand,” drawn by at-that-point series regular artist Mike Dringenberg, barely features Morpheus at all. As I said previously, there’s a major aspect of anthologizing in Sandman, and stories embedded within stories. It’s the major thrust of “The Doll’s House” arc, which doesn’t begin until the following issue, but even issue #9’s thematic prologue illustrates that Neil Gaiman is as interested in telling stories as he is in telling about the further adventures of his protagonist. In truth, Morpheus is presented here more as a spiteful force of nature than as a traditional hero. He isn’t the protagonist of this issue, a young woman named Nada is, and when she spurns him, because of the consequences of remaining with a god, he threatens her soul with “eternal pain.”

Nada’s story, an ancient one, is told by a tribesman—a grandfather speaking to his grandson as the young one completes his journey to become a man—and there’s the voice of an omniscient narrator who provides some context at the beginning and end, who tells us: “There is another version of the tale. That is the tale the women tell each other, in their private language that the men-children are not taught, and that the old men are too wise to learn. And in that version of the tale perhaps things happened differently. But then, that is a women’s tale, and it is never told to men.”

A story within a story within a story, self-consciously pointing out to us that other versions exist.

The danger in setting up such a structure is that it turns everything in the comic, and every previous and future issue, into “just a story.” None of it really counts, in that sense. But Neil Gaiman’s amazing feat, throughout this series, is that everything counts. The stories are what matters because this is a series that celebrates the art of storytelling.

“Tales in the Sand” reminds us of that, and also sets up the power of desire, even though Dream’s sibling, Desire-with-a-capital-D, only plays an on-panel role beginning in the next issue. We also get to see that Morpheus is not a pale, white, spikey-haired Goth rock-star looking guy. That’s just one manifestation of him. He takes on the aspect of whatever culture he presents himself to. His shifting appearance mimics the shifting narrative of stories told and retold.

“The Doll’s House” proper, as a complete, multi-issue story (with stories embedded within it, of course), begins with Sandman #10 and the striking, towering fortress called the Threshold, which is “larger than you can easily imagine. It is a stature of Desire, him-, her-, or it-self…and, like every true citadel since time began, the Threshold is inhabited.”

Here, Neil Gaiman expands the mythology of Sandman—we’ve already met Dream and Death of the Endless, but now we meet sweet and manipulative and vicious Desire and the hideous Despair—and that is another of Gaiman’s great achievements in the series: he creates a clear mythological structure that allows him to play with sibling rivalry on an epic scale while also providing embodiments for all the facets of humanity. Gaiman’s mythology doesn’t strain to present itself as meaningful, or to justify the connections between the characters in some kind of Tolkeinesque ancestral map, it just reminds us of the archetypal structures that we’ve already built in our minds. Dream and Death and Desire and Despair do exist, for us, and Gaiman gives them form, and, more importantly, personality.

Desire reveals that she had played a role in ensnaring Morpheus into a love affair with Nada, and she seems to have another scheme planned. But this is merely the frame story for The Doll’s House, and we don’t know what Desire is up to quite yet.

The overarching story, the guts of The Doll’s House, from Sandman #10-16, is the saga of Rose Walker, young woman with rainbow-colored hair. By the end, we learn that we’ve been following Rose through her journey because she’s central to Dream. She’s the “vortex,” and that means she’s going to have to die.

The vortex “destroys the barriers between dreaming minds; destroys the ordered chaos of the Dreaming…Until the myriad of dreamers are caught in one huge dream.” Then, it all collapses, taking the minds of the dreamers with it. If that were to happen, it would be…well…seriously bad.

So that’s the big story—Morpheus’s pursuit of Rose Walker, the vortex, and the eventual decision about her final fate—but in the hands of Neil Gaiman, it’s not presented as if that’s the big story at all. Instead, it seems to be about innocent Rose Walker’s perilous journey through a strange American landscape where killers dwell and nothing is at it seems. The vortex bit, a major part of the climax, seems barely important until you realize that it’s hugely important but Gaiman has been underplaying it to tell stories about smaller corners of the world Rose Walker drifts through.

What we end up with is Gaiman’s fantastical version of Alan Moore’s “American Gothic” arc from Swamp Thing, and it exemplifies Gaiman stepping out of Moore’s shadow, because even as Gaiman seems inspired by Moore’s counting-and-eye-collecting Boogeyman, he does Moore one better by putting storytelling before moralizing. “American Gothic” is some of the worst of Moore’s Swamp Thing but “The Doll’s House” is some of the best of Gaiman’s Sandman—expansive, evocative, chilling, and wondrous.

It’s no shock that it was the first thing from the series DC decided to reprint.

What else is worthwhile along the way, as we follow Rose Walker on her journey? Well, we meet Lucien, the librarian of the Dreaming, and in his exchanges with Morpheus the setting becomes more fully realized (and we get more hints about the connection between this Sandman series and the Jack Kirby, yellow-and-red dream warrior Sandman of the Bronze Age). We meet the strange inhabitants of the boarding house Rose stays at, including the spider-brides Zelda and Chantal, Ken and Barbara (whose fantasy world will play a dominant role a year into the series’ future, but we only glimpse its strangeness here), and Gilbert, the burly older gentleman who plays the role of Rose’s protector.

Gaiman’s G. K. Chesterton adoration comes through in the form of Gilbert, who is modeled after Chesterton himself, and while he looks like an unlikely hero, he is noble and brave, and, ultimately, not even human at all: he’s a piece of the Dreaming who has adopted corporeal form.

In my memory of this collection of comics, the Cereal Convention—actually a Serial Killer’s Convention—plays a larger role. But though Rose ends up at the same motel as the convention, and comes close to becoming a victim of Funland (the amusement park predator), most of The Doll’s House takes place before we even see the Convention, or get to the motel. The Serial Killer stuff is powerful—Gaiman’s matter-of-fact portrayal of evil is particularly unsettling—and the presence of Dream’s nightmare creation, the Corinthian, ties it all back into the story of Morpheus, but the divergences along the way are what make this batch of issues worth rereading.

And in the middle of it all, we get two consecutive issues by guest artists—what would be obvious fill-in issues in the hands of other creative teams—and these mid-arc single issues are two of the best of the entire collection.

The first is “Playing House,” from Sandman #12, drawn by a young Chris Bachalo. Amazingly, this is Bachalo’s first professional comic book work (what a debut!) and only a few months later he would go on to co-create the revamped and hallucinatory Shade, The Changing Man with Peter Milligan. In “Playing House,” Gaiman gives us a Sandman story firmly footed in the DC Universe—those kinds of stories would be less prevalent as the series unfolded—and we find out that Brute and Glob have concocted their own mini-dreamworld in the mind of a child, with the colorful DCU Sandman as their plaything. In then-current DC continuity the superhero Sandman was Hector Hall, and he and his wife Lyta (both former members of the second-generation superteam Infinity, Inc.), had a little homestead inside the dreamworld. The confrontation between Hall and Morpheus is a tragic one, since Hall “died” in Infinity, Inc. long before, and was living as Sandman on borrowed time. Morpheus puts him to rest, leaving the angry, grieving, and pregnant Lyta to fend for herself.

Hauntingly, Morpheus leaves her with these words: “the child you have carried so long in dreams. That child is mine. Take good care of it. One day I will come for it.”

That’s Gaiman’s protagonist. Hardly heroic. But a fitting pairing of word and deed for a god. And his statement has implications in future issues.

The following issue, unrelated to what comes before or after, except thematically, is Sandman #13’s “Men of Good Fortune,” guest-illustrated by Michael Zulli. This story gives Gaiman a chance to flash back in time to 1489, where we meet Hob Gadling, the man who will become Morpheus’s friend.

There is no narrative reason for this story to fall here, between the Hector Hall tragedy and the upcoming Serial Killer sequence, but it’s a perfect fit, because, as readers, we need something in Morpheus to latch onto. And his relationship with Hob Gadling speaks volumes.

Gadling is granted immortality, though he doesn’t believe it at first (who would?), and he and Morpheus schedule a centennial meeting, at the same pub in which they first cross paths. So Gaiman takes us from 1489 right up to 1989, 100 years at a time, sprinkling in historical characters and events along the way in what amounts to a time-hopping My Dinner with Andre, starring a reluctant immortal and the god of the Dreaming. The meetings humanize Morpheus for the reader, even though Gadling’s centennial check-ins are sometimes unbearably painful. Hob Gadling hasn’t always made the right decisions over the years. But he chooses life, ever time, even though he knows what it might cost in personal misery. And his evolving relationship with Morpheus, and Morpheus’s own acknowledgement of friendship, becomes the core of the story.

It’s quite a good single issue—in many ways the most direct symbol of the ethos of the entire series—and it feels uniquely Gaimanesque in its whimsical use of history and tale-telling, bound together inside something resonant and relevant to a larger sense of the mythology of Dream.

From there we go through the Serial Killer’s Convention and all the depravity that implies (with not a little vicious wit from Gaiman all the way through), until we get to the inevitable: Morpheus must kill Rose Walker, or else all dreamers will be destroyed by the vortex.

But that’s not what happens. Morpheus shows compassion. And we believe it because Gaiman has sprinkled in enough character moments to make us realize that Morpheus is more than a haughty omnipresence. Rose Walker may be the vortex, but she wasn’t meant to be. It was meant to be her grandmother, Unity Kincaid, who had slept for nearly a lifetime because Morpheus was imprisoned and dreams weren’t working properly. Unity gives up her life to save her granddaughter, and there’s yet another twist: Unity became pregnant while she was asleep all those years, and how did that happen?

Desire.

Rose Walker is the granddaughter of one of the Endless, and had Morpheus killed her, he would have unleashed…something. All we know is that Morpheus, once he has figured out the truth and brought it to his manipulative sister, implies that Rose Walker’s death at the hands of her own great-uncle would have entailed something unspeakable.

Morpheus admonishes her, and wraps up the frame of the narrative with these words, before leaving Desire alone in her hollow citadel: “When the last living thing has left this universe, then our task will be done. And we do not manipulate them. If anything, they manipulate us. We are their toys. Their dolls, if you will.” And he concludes with a promise: “Mess with me or mine again, and I will forget that you are family, Desire. Do you believe yourself strong enough to stand against me? Against Death? Against Destiny? Remember that, sibling, the next time you feel inspired to interfere in my affairs. Just remember.”

What began with Nada, and a tragic love story long ago, ends with the condemnation of Desire.

But for all of his words about the Endless as the dolls of humanity, the truth is that Desire is always impossible to control. And Dream knows it. We know it.

And the story continues.

NEXT: Four short stories bring us to a place known as Dream Country.

Tim Callahan, as a teenager, was so inspired by the Cereal Convention in the “Doll’s House” story arc that he submitted a dark-tinged story proposal to DC Comics in which some of those vicious characters visited the bayou of the Swamp Thing. He’s still waiting to hear back.

You read Desire as specifically female ? I always read it as in-between, gender-wise (which would equally gender-balance the seven Endless).

Like #1, I always read Desire as androgynous/non-gendered. Interesting.

Fluid and subject to Desire’s conscious control as well as responding to others, in my opinion; it particularly makes very little sense to specifically gender Desire as female in a story where Desire has impregnated a woman.

In my memories of this volume, the Cereal Convention does loom large, as well as the sheer profusion of surreal characters, whether they be imaginary, like the dreamed-of Sandman, or “real” like Rose’s various housemates. The permeability of dream realm and waking realm is what fascinated me in Gaiman’s stories, where one could be just as likely to find the more outre figures being the ones who walk among us as seemingly staid citizens with brilliantly flamboyant aspects to their lives (like Rose’s landlord, the one she first thinks is the “normal” resident of the house).

Dream warns Desire about “mess[ing] with me or mine”, yet he can offer immortality to Hob Gadling, which would look like he’s trespassing on sister Death’s territory. I guess it all depends on which End(less) is up.

On Desire’s fluctuating and indeterminate gender, you will notice that Gaiman never uses specifically gendered pronouns to refer to Desire, and Dream uses the address ‘sibling’, rather than ‘brother’ or ‘sister’, as he often does with Death or Destruction, for example.

I do really like this story and always enjoyed the idea of Lucien’s library, with all the books that might have been. It all adds to the multi-layered discussion of story, dreams and narrative that is just starting to build here (also, I don’t remember if we ever get the spider ladies’ further stories – do they appear again at a later point, as several other characters here do?)

I always thought of the offer of immortality to Hob Gadling as being much more Death’s thing than Dream’s. I went back and checked, and I still hold to that opinion – Death has brought her brother to the tavern to listen to the people, and maybe connect with them in some way (because he’s becoming far too detatched from his “clients” as it were – a problem which is emphasised all the way along the series, virtually from go to whoa. Morpheus’ main flaw is that he doesn’t know how to deal with his feelings, so he deals by not dealing). She’s listening to Hob along with her brother, and basically the pair of them hear Hob saying that death is avoidable, provided you’re committed to not going along with the flow. There’s a panel showing Death smiling at this (and she knows there are people out there who have been dodging her for a long time – we meet more of them further down the track) and then she offers Morpheus the choice – “Are you going to tell him, or am I?”

So it’s fairly clear the whole offer is made by Death, and with her blessing. Whereas Desire’s messing around with the Vortices is done unbeknownst to Dream, and turns out to be yet another move in a longer game the younger members of the Endless have been playing (the aim of which appears to be to establish who is the most powerful of them, after Destiny and Death; or at least, that appears to be the aim from the way that Desire plays the game – if we look at the way that Despair and Delirium play, it’s not so clear).

I always read the Cereal Convention as being about the fictional versions of serial killers rather than the sordid actuality and Dream’s dismissal of them as Gaiman’s dismissal of people who saw them as some kind of existential hero. This is backed up with the character of the bloke who pretends to be the Bogey Man. This would fit with the idea that this is a story about stories.

The Hob story was what really sold Sandman to me. I adored that story and so it was that I started seeking out the other trade editions.

Any thoughts on the degree to which Gaiman’s version of Death is a response/dialogue with Terry Pratchett’s version? After all, both authors had worked together on the novel Good Omens. I wonder whether the Endless Death is female and sparky as a direct response to the Discworld Death’s mordant humour and occasional pomposity.

Oh, and Desire is definately androgenous.

The spider brides Zelda and Chantal both turn up again in “The Kindly Ones,” along with many other characters from this story arc and others. One of them (Zelda, I think) is dying of AIDS, and Rose visits her in the hospital.

I always wished someone at Vertigo had done a miniseries focusing on Rose Walker as happened with some of the minor characters from “Sandman,” like the two Thessalystories or the Jack Pumpkinhead story that turned up in “The Dreaming.” I always found her to be a fascinating character

Yeah Desire is adrogenous but more often than not seems to drawn more feminine. Also as others pointed out Death had to agree not to take Hob, this was after Dream and Death overheard him saying that the way to live for ever is to simply not die. This notion was touched upon again in a different way when two characters( I unfortunately do t remember the s act circumstance) were talking about swimming and a fear of drowning, where one character said the trick to not drowning is simple: don’t drown. I believe this all ties into the themes of responsibility, both personal and professional that run through the series. Dream feels an obligation to his duty and couldn’t fathom simply walking away from it as see rap other characters do.

We actually meet another D-word in “Doll’s House”: Destiny is in the foreword.

I always felt Desire’s appearance to be fluid, and to reflect the desires of the person Desire interacts with.

The male/female aspects are fascinating. The Nada story is one told to men, not that surprising given the protagonist is male too (as is the writer), but the meta aspect is that the expected readership of the comic at that time would be predominantly male too. Does Desire look look more often feminine for the same reason?

(Irrelevant aside: I had looked at the first issue of Sandman, but decided it wasn’t my cup of tea. It wasn’t until the lady at the comic shop recommended it that I picked up “Doll’s House” & got hooked. Which is also why I agree with the publishers & recommend beginning reading with “Doll’s House”, then “Preludes & Nocturnes”, then the rest in publication order.)

Dream isn’t a god, he is one of the Endless. Gods exist at the whim of their human believers (a point that showed up in American Gods, too), while the Endless exist far beyond.

Hob Gadling is probably what actually got me hooked on Sandman.

I think Desire’s perceived femininity is more about our culture than anything. A man with feminine traits is seen as less than male, whereas a woman with masculine traits is still seen as less than male. Thus, anything presented as androgynous automatically seems more “female”.

1. Desire “was never satisfied with one of anything”, so we may take it as explicit in the narrative, if not in the artwork, that it has at least two sexes and two genders. Although Desire actually tells us it fathered Miranda without any transmission of semen (“Of course. Unity’s body just thought there was”), which would make it definitely not biologically male, which opens up all kinds of oddity.

2. Consider if Lyta turns into the insanely overprotective mother we see in “The Kindly Ones”, whose mental unbalance ultimately brings on Dream’s downfall, because Dream tells her to take good care of her child. He doesn’t let himself know what he’s doing yet, maybe. . .

3. How great is Mike Dringenberg? They really let his pencils soar on a couple of occasions here, for Gilbert’s version of Red Riding Hood and Dream’s resuscitating Rose, and these couple of panels are maybe the most powerful in the entire series – and such gentle, delicate power it is, even when rendering a wolf’s head in stark red, black and white. Words fail me.

I’ve never actually been a huge fan of the Rose Walker stories when rereading the series, although I love the Hector/Lyta bits here and can never shy away from reading Hob Gadling. Could be part of that whole “stories told to men and stories told to women” bit in it’s own way, eh?

I also loved when I later read trades of Hellblazer and realized the connection the convention storyline had to Delano’s “Family Man.”

Keep it up Tim — I may not always agree with your interpretations on things, but you remain my favorite comics commentator (from the old pre-book Grant Morrison stuff on the original Seqart on…)!

While the influence of the Endless is subtle and powerful, I ascribe Lyta’s overprotectiveness less to a subconscious compulsion from Dream and more to, well, the ultrapowerful being that took her husband away casually mentioning that he’d be back to take her son too. Most of us would become somewhat paranoid at that point. It’s definitely Dream setting up his own downfall, but at this point in the series I don’t think it’s deliberate; that lack of empathy is disastrously characteristic of Morpheus.

Well, Greenygal, there’s that too, of course. Morpheus is such a fine manipulator (not that that’s such a fine character trait) because he can give people a hundred reasons to do what he wants or think what he wants with just a single act or sentence. But mostly I was thinking of how Delirium’s speech on responsibility later on might apply here, how we can see the Endless deforming the universe just by passing through it.

Thanks for the referral. Neil Gaiman is usually pretty legit, but it seems that one has to be pretty far into this story already in order to get an idea of what’s happening.

In which issue does the storyline start?

(Please forgive my ignorance! Ha.)

Sorry to be pedantic, but I just have to point out that Dream’s first encounter with Hob is 1389, not 1489. Geoffrey Chaucer is in the tavern, and he died in 1400. Second meeting (“chimblies” & book publishing) is 1489. Then Shakespeare in 1589, destitute Hob in 1689, slaver Hob meeting with Johanna Constantine in 1789, Jack the Ripper references & Dream getting mad at Hob in 1889.

Acho um pouco exagerado dizer que o American Gothic de Alan Moore é ruim. Isso pra dizer o mínimo.