About 16 years ago, for one school year, I was hired to tutor a teenager who was creative and artistic but wasn’t particularly inclined to do any of his homework for class. I could guide him through his math work, and I remembered enough Latin to help him with that, but it was really in his writing assignments that I could see his growth, as I worked with him to turn his ideas into somewhat refined arguments. He was a good kid, and he worked hard for me, even though he was rarely interested in the topics he had to tackle for homework. And when we got off track, and conversations meandered before getting back to work, he’d talk about his drawings and the characters he would create.

But he didn’t read comics. They just weren’t part of his life.

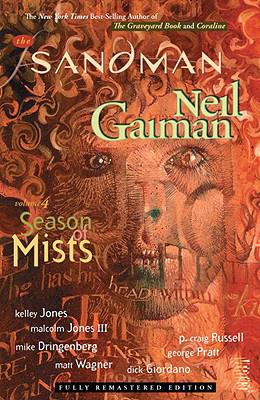

On my last day of tutoring, as the school year came to an end, I gave him a copy of Season of Mists, the fourth Sandman collected edition.

It seemed like exactly the right gift for him, with its exploration of mythology and its philosophical musings, but with an emphasis on odd, shadowy artistry.

I never saw him after that, so I never found out if he liked the book—or if he even read it—but I’ll always think of Season of Mists as the kind of story that’s built for farewells, even though Neil Gaiman’s Sandman wasn’t yet half over as a series, and, in many ways, Season of Mists is when the comic crystallizes into what it was always meant to be. It’s the first confident story arc in the series. The first one that has a beginning, middle, and end revolving around Morpheus that doesn’t owe its more substantial moments to what Alan Moore had done on Swamp Thing or what Gaiman’s other favorite writers had done elsewhere. In Season of Mists, Gaiman builds the larger universe of the Endless, and the gods, minor and major, who serve them. And he tells a heck of a good story.

Kelley Jones provides most of the pencil art for Season of Mists, with Mike Dringenberg giving us the opening issue set-up, and Mage and Grendel creator Matt Wagner drawing a story-within-the-story about a zombie prep school. That’s something this arc has less of than any of the previous arcs, by the way. No, not less zombie prep schools, but less examples of stories-within-stories. Gaiman’s Chaucerian tendencies will color the series for most of its run, and I’ve certainly mentioned plenty of examples of nested stories in previous posts, but Season of Mists mostly tells a linear narrative about Morpheus planning to descend into Hell to rescue his former beloved, and then his difficulties with the consequences of everything that follows his return.

It seems to be an even more typically-conceived quest narrative than Gaiman’s opening arc, except Gaiman knows that’s how it seems—that it’s just a delicate Hercules-in-the-Underworld story—so he subverts it. The Dream King faces no opposition in Hell. Instead, he’s given the keys to the kingdom, and that is a potentially more diabolical trick to play on Morpheus than even the most fiendish battle plans.

But that comes later in the story.

First: the family.

In the twenty issues that preceded Season of Mists, Gaiman and his artistic collaborators introduced most of the members of the Endless. We had met Dream, of course, and Death. And Desire and Despair. And Destiny had popped up, but makes his presence felt more fully in the opening chapter of this arc. And, here, we are also introduced to Delirium, the unstable pixie of a sister, and a missing brother (Destruction, though his name is never spoken in this arc) who has cut off all ties with his family, for reasons to be explored in future Sandman stories.

Starting the arc with a family meeting, one that helps to more firmly define the rules and relationships between these characters, gives Season of Mists more of a sense of completeness than any other Sandman arc. Gaiman may not have been thinking about the collected editions of his works at all, but this is the first arc that feels like it could have been written with a future collected volume in mind. It references some earlier stories and points toward future tales, but it also gives you the entire picture of Morpheus’s world in this opening chapter, and tells a story that resolves by the end of Season of Mist’s final issue.

Perhaps that’s another reason why I’d chose volume 4 of an ongoing series as a gift for someone, all those years ago.

The opening issue of this story also shows Morpheus in a less-than-flattering light. He’d been shown to be haughty and distant before, strange traits for a protagonist that we were supposed to root for, but it was easy enough to dismiss those traits as temporary. As something lingering because he’d been imprisoned for most of the 20th century and he wasn’t yet up on the latest fashions of appropriate lead character behavior. And while that may be true, in this first Season of Mists chapter, Death doesn’t hesitate to tell Morpheus that he’s done something terribly wrong and he needed to do something to fix it. Death wasn’t going to wait for her brother to learn and grow as a character. She wanted him to acknowledge his mistake and correct it by rescuing Nada, the woman he had once loved, out of the Hellfire in which he had condemned her.

The truth is that Morpheus was coming to that realization himself—he was starting to grow and change since his escape from imprisonment—but he needed some prodding. In rereading this, I was surprised by how unlikable Gaiman is willing to make his title character, even in these almost-the-middle-of-the-series issues. In so much of popular culture, and in so many stories designed for mass consumption, there’s an eagerness to please the audience, and Season of Mists seems defiantly uninterested in that. Gaiman seems defiantly uninterested in that. He doesn’t look like he’s ready to pander to the crowd in this story arc, and so he’ll do things like present an unsympathetic hero slowly recognizing some of his previous faults. He’ll throw in Miltonic passages and make hypothetical philosophical questions into narrative reality. He’ll present the gods of a variety of pantheons and then give us not some arena battle between mythic opponents but courtly arguments, well-reasoned. And in the midst of it all, he’ll detail the horrific adventures of a young boy facing the worst school year of his life, in what he’ll admit in the afterword of Absolute Sandman Volume 2 was a slice of near-autobiography. Though, presumably, in real life, young schoolboy Neil Gaiman didn’t literally have to face off against the undead.

That one chapter, the fourth part of Season of Mists, with the prep school full of spirits risen from the grave, would eventually spin off into the “Dead Boy Detectives,” as written by the likes of Ed Brubaker and Jill Thompson. A pretty great title for a spin-off, even if the comics with that title aren’t highly regarded. I’m not saying they aren’t good. I just know that I read them and don’t remember anything in them quite as definitely as I remembered what happened in their first appearance here. Better for them to have stayed dead, perhaps.

Then there’s Lucifer. The Lord of Hell, the first of the fallen, abdicates his throne as Morpheus is preparing for his journey into the depths. Lucifer leaves Hell to Morpheus to do with it what he will. And that’s when all the gods come a-knockin’.

Lucifer, too, would spin off into non-Gaiman written comics. Nearly seven years worth, as a matter of fact. All of them written by Mike Carey. Some people seem to like them.

But as far as Season of Mists is concerned, Lucifer’s deed—granting the key to Hell to Morpheus—not only slides Nada out of Morpheus’s reach, since all the souls in the Underworld have been set free, but it also makes Dream the steward of a land he doesn’t want. Luckily for him, it’s a powerful piece of real estate, in the greater scheme of things, and everyone else wants it for their own purposes, from Odin, Thor, and Loki, to Anubis, Bast, and Best. From Susano-o-no-Mikoto to Azazel, Merkin, and Choronzon. I could go on. Name a pantheon, and someone was probably sent to Lord Morpheus’s realm to represent their interests.

Gaiman presents all of them with distinctive personalities, and he shows throughout Season of Mists his deftness with handling characters of great dignity and resonance while giving them voices that show their vulnerabilities. That’s one of the secrets of why Sandman works so well, with these nearly omnipotent beings at the center: Gaiman knows how to humanize them without making them seem silly or weak. He just makes them seem real. And imperfect.

In the end, Morpheus does rescue Nada—the duplicitous Choronzon, demonic middle-manager of the former Hell, was hiding her soul—and he gets divine guidance from a voice above who tells him what he must do. Yes, it’s literally deus ex machina, as the word of God makes a case for his angelic emissaries as the only righteous choice for guardians of Hell. It will be as it always was: a shadowy mirror of Heaven, run by former members of the heavenly host.

It’s a conclusion that puts things back where they were. By the end, Hell is returned to its former horribly vile glory, only this time run by creatures of light who punish the wicked out of love instead of hate (which makes it “so much worse,” according to one of their tormented victims). Morpheus has only his dream kingdom to worry about. And the only thing that’s changed is that Nada has been set completely free, and she’s chosen reincarnation, though she won’t remember her past life. But her soul will continue on, in the body of a newborn babe.

Nothing has changed, but everything has. That’s what stories do. And while Gaiman leaves threads for himself and others to pick up and weave into new tales in future issues, in future years, when Season of Mists reaches its final page the story that has unfolded in its pages has come to a satisfying end.

NEXT TIME: Inside Barbie’s fantasy world Sandman gets caught up in A Game of You.

Tim Callahan prefers Neil Gaiman’s version of Thor and Loki to pretty much every version he’s ever read. A little Thor goes a long way.

This was always my favorite collection in this series, followed quickly behind by Dream and Delirium finding their brother and then Morpheus’s son. The world-building with the Endless was always my favorite part of this series.

As for Lucifer, if anyone hasn’t read it yet, I definitely suggest they do. I can tell if Tim is being coy or doesn’t really care about the series. Regardless, I find Mike Carey’s Lucifer book to be the equal of Sandman, if not superior.

The themes that Carey explores through that book really resonated with me, and he brought so much power to the characters he was working with. In particular, Michael, Lucifer, and God himself. Such a good series.

when this read started i was startled by the mention of “lucifer.” i bought a copy five years ago and still haven’t read it. i did pull it off the shelf however, so it’s about six feet closer to being read.

I like Season of Mists, of course, but the inconsistency of the art bugs me. There’s pages where the same character looks distractingly different from panel to panel. That keeps me from re-reading it as much as some of the other volumes. I’ve also always wondered about Gaiman’s portrayal of Susano-o, which goes against everything Japanese myth says about the character…

I ignored Lucifer for many years figuring it was just a lazy cash-in, but it really is quite good. I’d say Lucifer and the Little Endless Storybook are the only must-read Sandman spinoffs.

Lucifer’s a perfectly solid comic, but it’s in no respect better than Sandman. I read the whole run and enjoyed it, but it’s not as memorable, not as significant in the field, and just not as well-written as Sandman, for all the occasional flaws of the parent series.

Agreed that this is where Sandman finally finds its independent voice and drifts away from the DC universe with superheroes being replaced by the mythical gods that inspired them.

I’m not up on Japanese myth and legend so cannot comment on the accuracy of Susano-o, but he’s spot in, imho, with the Norse gods and the envoys from Faerie.

Entertainingly, the prep school sequence draws from the same well of school stories that partly inspired Harry Potter.

I’m with Sanagi as to the distractive artwork. This book has some bold experiments, sometimes several different ones per page, but half the time I can’t even guess what they thought they were doing. It might be a presentation meant to mirror that of Paradise Lost, where the style of the story is often more evident than its substance.

But otherwise, yes, it’s a powerful story. Gaiman himself seems to attribute it mostly to Lucifer, who he describes as a character with his own agenda and his own momentum who you don’t write so much as get out of the way of. Mike Carey found the same thing, too. . .

And it’s a resonant story. The scene where the Devil walks out of Hell? I’ve seen that repeated in like five different comics. Not homages or anything, I mean literally the same scene – like when Jill Thompson bases an entire book on the events of this book from Death’s perspective. But it’s probably no less than it deserves.

I consider the two testaments of the Bible, Paradise Lost and Lucifer equally canonical parts of the same story, and this is the middle chapter between the latter two. Which makes Season of Mists a key chapter in our world history, going back six thousand years and who knows how far into the future. It’s weighty, archetypal stuff. And it’s probably good enough to be remembered as such.

The only sad part is the boarding school chapter is likely to be the first to be forgotten, five hundred years from now or so. Though maybe people will fill in their own ghost school stories. I can see it now; which elements will always be the same. The mists (of course), the lonely boy, the old school, the dead who come back, the mean old boys, the lost little boy, the unexpected friendship, the escape from a distracted Death. Yes. And then 525 years from now Future Joss Whedon will deconstruct it in a movie called Boarding School in the Woods.

I read this Seasons of Mists story a few years ago, and was always bothered by the deus ex machina ending. I suppose some folks might say that this was how it had to end, and others might say that NG was following some archtypal story structure all along. Not having an in-depth classics background, I just knew enough that deus ex machina endings were usually considered cheating by modern audiences. That said, it’s interesting to me that Tim concludes that this still leads to a satisfying end, perhaps solely because of the change for Nada. But I’m curious how NG can pull off such an ending in a satisfying way and yet most modern writers would avoid this.

Given NG’s in-depth understanding of story, I suppose if I could ever have a conversation with him, I would want to ask about this.

*disclaimer – I still haven’t read the entire Sandman series, so if the ending is in place to set up a future story, that might assuage my feelings about the end.

It does seem at the end that nothing changed but as we will learn later things have changed and those changes will have effects that ripple through other issues.

@7 It is important to keep in mind that while we the audience reading this series didn’t realize that NG had a story arc in mind he did. What is amazing is that he produced such a great work with a sweeping story arc. Dream is doing things with one hand while hiding them from himself with the other all of this with an agenda starting with his capture at the beginning. I wonder if you could go back and track how the magus got his hands on a spell to pipe Dream of the Endless down you wouldn’t find somewhere Dreams touch.

@8 – Thanks Tom! I will sequester myself from Tim’s remaining columns until I can reread the entire series, and then consider the story arc. Great advice.