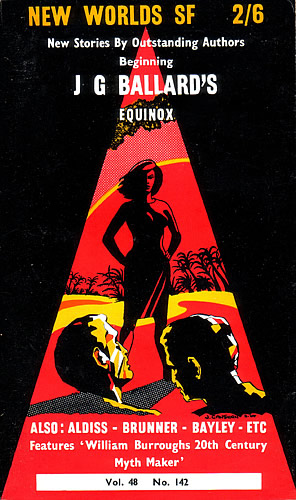

Just shy of half a century since the young Michael Moorcock took the editorial helm of a long-running magazine called New Worlds and ushered in a new age of avant-garde science fiction, it appears that we might be in the throes of the birth of a new New Wave.

The original New Wave moved away from shiny futures and bug-eyed monsters and offered more experimental literature, both in technique and subject matter, perhaps best exemplified a couple of years later in 1967 when Harlan Ellison released his Dangerous Visions anthology, bringing new voices, new ideas and a new way of telling stories to take over from the rocket-ships and square-jawed heroes that had gone before. New Wave also brought to the fore many more female writers, such as Joanna Russ and James Tiptree, Jr.

But does the emergence of a new aesthetic in (largely) contemporary British SF signal a similar movement nearly 50 years on?

If so, it is perhaps fitting, then, that one of the main proponents of our New New Wave has nods to the past both in its title, which hearkens back to the Golden Age supplanted by New Wave, and by including an interview with Moorcock himself.

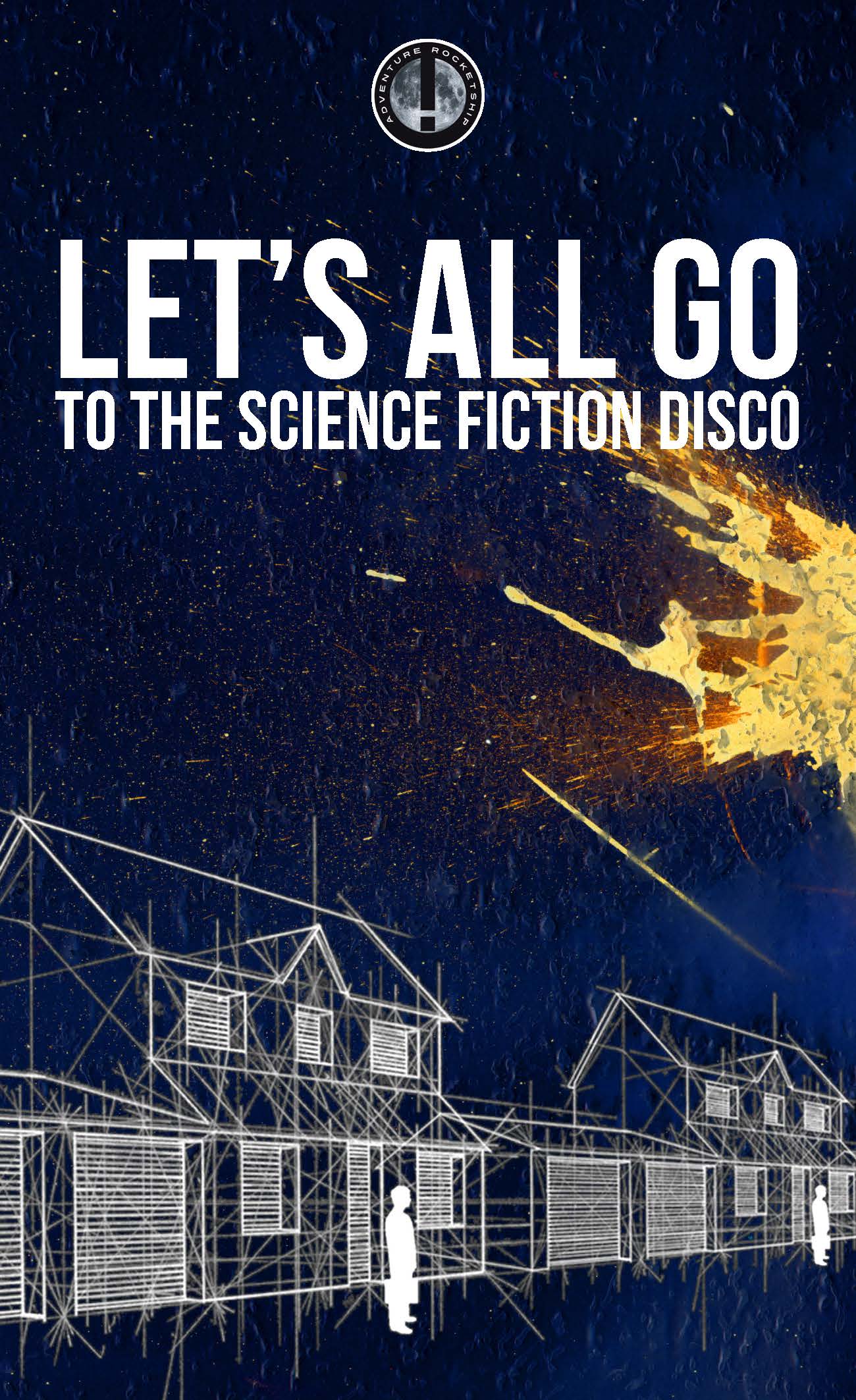

Just like the New Wave never set out to be a movement, neither do those involved in the New New Wave; rather, it is serendipity that they’ve all come together at roughly the same time to create a bit of a buzz in the SF world. Adventure Rocketship! is a new publication edited by writer and journalist Jonathan Wright, which includes fiction, interviews and criticism. It was, says Wright, loosely modeled on The Idler: “I love the idea of a series with its own evolving aesthetic. Also, while being fascinated by digital projects, I still love the idea of the book as object. In the case of Adventure Rocketship! the idea is on one level really as simple as a leftfield SF anthology or even magazine in book form with each issue themed. The first issue, “Let’s All Go To The Science Fiction Disco,” is about music, SF and the counterculture—and the space where they meet.”

With a cover by Stanley Donwood (aka Dan Rickwood, artistic collaborator of Radiohead) and interviews with Mick Farren and The Orb, as well as new writing by Liz Williams, N.K. Jemisin, Jon Courtenay Grimwood, and David Quantick among many more, Adventure Rocketship! ably fulfills its brief. But why did Wright decide the time was right to try something new?

With a cover by Stanley Donwood (aka Dan Rickwood, artistic collaborator of Radiohead) and interviews with Mick Farren and The Orb, as well as new writing by Liz Williams, N.K. Jemisin, Jon Courtenay Grimwood, and David Quantick among many more, Adventure Rocketship! ably fulfills its brief. But why did Wright decide the time was right to try something new?

He says: “I’ve written about SFF literature for SFX for a long time now (I’m old enough to have covered the turn-of-the-millennium Brit New Wave—China, Jon Grimwood, Al Reynolds et al—and now am watching a bunch of younger writers snapping at their heels) and over those years I’ve detected a loosening up among genre fans about how they think about SFF. SFF fans now, especially younger fans but by no means exclusively—and yes this is a huge generalisation and I’m really, really not getting at anyone here—seem more open to different ways of thinking about / approaching the genre. Broadly speaking, that’s the audience I’m suspect I’m trying to address. It’s interesting to me that a writer such as David Quantick immediately seemed to get what Adventure Rocketship! was about, as did the Pornokitsch guys.”

The “Pornokitsch guys” are Jared Shurin and Anne Perry, who have grown their output from a criticism/review site to encompass their progressive fiction awards, the Kitschies and a boutique publishing company, Jurassic London, which puts out beautiful and forward-thinking SF, and who are quite rightly part of the vanguard of the New New Wave. Their latest publication, The Lowest Heaven, is due to be published on June 13.

Shurin says: “There’s been a lot of discussion about science fiction being dead—or even worse, exhausted. But a lot of that is based on a very rigorously, very traditional definition of the field. Elements of the speculative are everywhere, in every section of the bookshop. Science fiction isn’t retreating, it is evolving.

Shurin says: “There’s been a lot of discussion about science fiction being dead—or even worse, exhausted. But a lot of that is based on a very rigorously, very traditional definition of the field. Elements of the speculative are everywhere, in every section of the bookshop. Science fiction isn’t retreating, it is evolving.

“What we’re really proud of with The Lowest Heaven is how authors have taken fresh approaches to science fiction’s first and strongest inspiration—space and other worlds. Maybe the book isn’t “traditional SF”—the stories draw just as much romance, mystery, history, fantasy, horror and kitchen sink lit-fic—but it reflects the wonderful, adaptive new direction that the field is taking.”

It would be churlish, really, not to mention at this point the long-running Interzone SF magazine and its sister publication Black Static, which aims for a cerebral horror/slipstream market. But both Adventure Rocketship! and Jurassic London feel new and fresh, complementing rather than supplanting Interzone. And coming along roughly together as they do, it really does feel like a burgeoning movement, one rounded out by Arc magazine, a digital quarterly from the makers of New Scientist and edited by author Simon Ings, which was created in order to feed New Scientist’s readers’ desire for speculative fiction based on the very real technological futures served up by the main magazine.

Tim Maughan has written for both Arc and Adventure Rocketship! is what you might call a non-traditional SF writer—he says before he started writing he didn’t even read much SF, and after having no luck getting his stories published through the “traditional channels” decided to self-publish—retaining a degree of control mirroring his background in electronic music, where independence is feted.

He isn’t sure if there actually is a New New Wave, nor if one is needed, but adds: “There are people kicking against the status quo, and we need them. We need more of them. The ferocity of my opinion shifts from day to day, but right now if you ask me about science fiction I’d suggest it was burnt down to the ground. Nuked back to year zero so we can all start again. It’s just, largely, lost its way. Itås stopped being about ideas, the present or even the future and has just become another slack-jawed asset of the escapist entertainment industry.

“I guess there are some very clear parallels with [British New Wave]—that movement was very important to me personally—Aldiss and in particular Ballard are huge influences. But I’m also cautious of the comparison, just as I’m cautious of when I’m compared to cyberpunk. It seems impossible for anyone to review my stuff without mentioning cyberpunk—which is a huge compliment on one hand, as it was a very important movement to me also, but on the other hand…it’s not the 1980s anymore, just as it’s not the 1960s either. Again I think this is part of SF’s apparent fear of the new or unidentified—it just wants to put everything in a box. ‘Computers and the near future? That goes in the box named cyberpunk. Next?’.”

In a previous interview with Michael Moorcock, Jonathan Wright asked him if the experimental SF writers, such as JG Ballard, were now essentially part of mainstream literature. Or in Wright’s own words, have “the SF novelists stormed the citadel and, while we’re still in the midst of a long siege, basically ‘won’?”

Moorcock told him: “I’ve been saying this for some time. Look in the popular bestseller lists or the literary lists and it’s pretty evident that the incorporation of those SF conventions happened a while back, perhaps without us noticing. Of course, the SF fan, like the rock and roll fan before him, is the last to realise this and goes on shouldering a weird sort of inferiority complex when in fact he’s in the majority now.”

Wright finishes: “It’s a rather trite observation, but our day-to-day world has in lots of key ways become science-fictional. No, we didn’t get personal jetpacks, but we’ve got the internet and mobile phones. How do we write about this? The realistic novel in its strictest sense doesn’t seem equal to the task, but nor funnily enough does science fiction. Solution? As ever, think about stuff, then try stuff, see what works.”

David Barnett is a journalist and author whose first novel for Tor Books, Gideon Smith and the Mechanical Girl, is released in September 2013. He can be found at his website or on Twitter @davidmbarnett

[…] in 1967 when Harlan Ellison released his Dangerous Visions anthology, bringing new voices, new ideas and a new way of telling stories to take over from the rocket-ships and square-jawed heroes that had gone before.

Less new voices than the other two things: by my count, of the 33 authors in the book, only 9 debuted in the 1960s. A couple of minutes of fiddling suggest the breakdown of fiction authors in DV by debut year looks something like this (length of career to date when DV came out in brackets):

1930s (5):

Isaac Asimov: 1934 (33)

Robert Bloch: 1934 (33)

Fritz Leiber: 1934 (33)

Lester del Rey: 1938 (29)

Theodore Sturgeon: 1938 (29)

1940s (8):

Damon Knight: 1940 (27)

Frederik Pohl: 1940 (27)

Brian W. Aldiss: 1946 (21)

Miriam Allen deFord: 1946 (21)*

Philip Jose Farmer: 1946 (21)

Poul Anderson: 1947 (20)

Harlan Ellison: 1949 (18)

Kris Neville: 1949 (18)

1950s (11):

John Brunner: 1951 (16)

Philip K. Dick: 1952 (15)

Joe L. Hensley: 1953 (14)

Roger Zelazny: 1953 (14)

Carol Emshwiller: 1954 (13)

Robert Silverberg: 1954 (13)

Henry Slesar: 1955 (12)

J. G. Ballard: 1956 (11)

David R. Bunch: 1957 (10)

R. A. Lafferty: 1959 (8)

Keith Laumer: 1959 (8)

1960s (9):

Sonya Dorman: 1961 (6)

Samuel R. Delany: 1962 (5)

Larry Eisenberg: 1962 (5)

Jonathan Brand: 1963 (4)

John Sladek: 1963 (4)

Norman Spinrad: 1963 (4)

Larry Niven: 1964 (3)

James Cross: 1967 (0)

Howard Rodman: 1967 (0)

Granted, the 1960s are hobbled by being only about half-over when Ellison began this project but still, veteran authors were well represented. I make it a total of about 495 total years of career, an average of 15 years and a median of about 14 years.

* Miriam Allen deFord’s non-sf writing career goes back a bit farther, to 1912.

Of course it’s evolving. In a few ways, we are living the future speculated upon by the earlier sci fi authors. However, our focus has shifted. In the 60s, our progress into space was rapid and seemed both unstoppable and full of promise. Now, our space program as a race lies atrophied while we are content to chuck automated satellites into near earth orbit. Meanwhile, we are thinking of what humans ARE more than what they might DO. This seems well reflected in modern sci fi. Sci fi will always cover the gamut, it always has, but the majority will fairly well reflect what humans are doing at the time.

At the risk of dragging facts into an otherwise satisfactory conversation, the general long term trend in space exploration is for it to increase in funding, ambition and number of nations involved with time. People get misled by Apollo, which was a highly atypical event.

See, for example, this willfully hurtful graphic, which inconsiderately undermines the narrative that space exploration is stuck in LEO.

http://users.rcn.com/ilya187/TimeGraph.html

It’s been FIFTY YEARS since Dangerous Visions?!? Damn I’m old…

As I recall the American and British New Waves, they grew out of frustration with the limits placed on the authors by genre and publishing conventions (Gordon R. Dickson, generally a meat and potatoes sort of SF author, had a cranky essay about e.g. being forced to cram his plots into the short page counts allowed in the 1960s). I guess if one is hoping for a New New Wave, the fact that modern F&SF has its own sets of restrictive genre and publishing conventions is good, because maybe they will piss authors off enough to push back against them.

I just wish the restrictions weren’t ones I thought we buried back in the 1970s. Who in 1980 would have imagined a woman being told she couldn’t write hard SF or rather that if she did, her publisher wouldn’t publish it?

FORTY SIX YEARS! ONLY FORTY SIX!

(Say, did people know the average university frosh next year was born the same year Buffy the Vampire Slayer debuted on the WB?)

James Davis Nicoll @6

Now I’m starting to feel old…

I felt old this year when I realized the stage manager I was ASMing for was younger than my oldest cat.

James – this is a cruel thing to ask, but what about Again, Dangerous Visions? (I always thought that was the better of the two)

*sob* You know if you scatter poppy seeds in front of me, I have to count them, right?

Take the numbers with salt. I like to do this stuff in my head to try preserve plasticity.

ADV

1930s

Ross Rocklynne: 1935 (37)

Ray Bradbury: 1938 (34)

1940s

James Blish: 1940 (32)

T. L. Sherred: 1947 (25)

1950s

Lee Hoffman: 1950 (22)

Chad Oliver: 1950 (22)

Kurt Vonnegut, Jr.: 1950 (22)

Bernard Wolfe: 1951 (21)

Gene Wolfe: 1951 (21)

Richard A. Lupoff: 1952 (20)

Andrew J. Offutt: 1954 (18)

Kate Wilhelm: 1956 (16)

Ben Bova: 1959 (13)

Joanna Russ: 1959 (13)

1960s

Ursula K. Le Guin: 1961 (11)

Terry Carr: 1962 (10)

Thomas M. Disch: 1962 (10)

Gahan Wilson: 1962 (10)

Piers Anthony: 1963 (9)

Ray Nelson: 1963 (9)

Leonard Tushnet: 1964 (8)

Robin Scott Wilson: 1964 (8)

Gregory Benford: 1965 (7)

Josephine Saxton: 1965 (7)

M. John Harrison: 1966 (6)

H. H. Hollis: 1966 (6)

Dean R. Koontz: 1966 (6)

Burt K. Filer: 1967 (5)

Barry N. Malzberg: 1967 (5)

James Sallis: 1967 (5)

James Tiptree, Jr.: 1968 (4)

David Gerrold: 1969* (3)

1970s

Joan Bernott: 1970 (2)

Edward Bryant: 1970 (2)

Richard Hill: 1970 (2)

Evelyn Lief: 1971 (1)

Parra y Figuéredo: 1972 (0)

John Heidenry: 1972 (0)

James B. Hemesath: 1972 (0)

David Kerr: 1972 (0)

J. A. Lawrence: 1972 (0)

Ken McCullough: 1972 (0)

Andrew Weiner: 1972 (0)

Total career years: 450

Average 10 yrs

Median 7 yrs

* Not counting TV work

I’d be happy to do this for The Last Dangerous Visions if someone could just clarify what publication date I should use.

@11: June 1979 Locus is the one on the ISFDB.

When I look at the books being printed and the e-books available, I have to think science fiction has expanded greatly since I started reading it way back in the late 50s. Once, to qualify as SF, the story had to have some hard science in it, however warped or twisted. Then things were BEMs and adventure storues set in outer space. Come the new wave, which I felt had much too much sex, drugs, and soft science, and the adventure turned to inner space. Cyberpunk and it’s child Steampunk shook things up. I found some authors, not naming them, who tried to return to the ‘experimental’ form with story extracts mixed together and laced with the old sex and drug formula. These days the field is so wide, we have sub-genres. The best science fiction has always set up a “what if” question and tried to answer it. The rest is just set dressing.

Thanks James! That’s weirdly good to know!

Hey, if people want a series of bean-counting articles, I would happy to supply them. I probably would not be able to resist….

I read quite a bit of the classic SF back in the day, and still have a lot of those books. Looking back, the hard science was all too often balanced with totally conservative, even reactionary social attitudes – the 50ies family with its gender relations was taken to be so much the norm that it was thought to still apply centuries later, and the 50ies were already socially conservative for their time. Much of that fiction is now dated just because of that major blind spot, plus the often unconvincing and flat characters.

The unreasonable optimism and human triumphalism that made much of classic SF so entertaining and even exhilarating, seems a bit pathetic with hindsight.

The current crop of SF is by and large more interesting and better writers overall, but I feel that there is always room for more and better SF. Bring it on!

Looking back, the hard science was all too often balanced with totally conservative, even reactionary social attitudes

OK, hands up everyone who, like me, missed the subtext in H Beam Piper’s “A Slave is a Slave”? I’m from Canada, we don’t have Lost Causers up here.

(But he has a third of the technical workforce in the time of Cosmic Computer be women, so he wasn’t completely reactionary)

I am currently working my way through the archives of CBS Radio Workshop. It started off with a two-part adaptation of 1932’s Brave New World (with an appearance by Aldous Huxley) and one thing I noticed is that while I personally would not want to live there, Huxley never manages to make the case that BNW’s bad ideas are worse than the bad ideas of the 1930s (when it was written) or the 1950s (when it was adapted). He thinks he does, though, because some things he took for granted growing up are gone in BNW and means of brutal oppression of the underclasses have changed a bit.

The unreasonable optimism and human triumphalism that made much of classic SF so entertaining and even exhilarating, seems a bit pathetic with hindsight.

Yeah, the unrelenting one-note grim darkness of grim dark doom isn’t much more interesting, although at least it gave me my current litmus test for how off-putting a book is: If I can say

“At least it didn’t have any plucky and sympathetic transsexuals tortured, eaten and killed – in that order – by cannibalistic Koreans.”

then I feel the experience of reading the book was not as bad as it could have been.

the unrelenting one-note grim darkness of grim dark doom

I forgot “now with graphic rape scenes replacing every paragraph break!” My record for longest stretch of books sent to me for review where each book had at least one rape scene is currently 46 in a row. In defense of the authors responsible, many of them are terrible people whose stunted imaginations render them incapable of conceiving of another use for female characters.

@17: Did you see io9’s review of The Testament of Jessie Lamb?

Yes. In defense of The Testament of Jessie Lamb while the idiot teenager protagonist’s decision is stupid, she’s an idiot teenager. Also, The Testament of Jessie Lamb didn’t have any plucky and sympathetic transsexuals tortured, eaten and killed – in that order – by cannibalistic Koreans so at least there’s that.

Also, I am used to the fact that the sets of “books James thinks are too stupid for words” and “books that attract critical acclaim” overlap.

Adventure Rocketship! doesn’t remind me so much of New Worlds or Dangerous Visions as it does the old Ace bookazine Destinies, of which I believe there are a number of fans on tor.com. Of course, this impression will probably change once I read AR….

Sorry- I got caught with this subtext- that’s right, let Zhorzh do it.

What else happened about 50 years ago? The Cuban Missile Crisis!

So now we have technology involved in global economic crisis. Cheap computers and robots and what to do with technology in education.

But it is so curious that we cannot make double-entry accounting mandatory in our schools when accounting was among the first things done with computers in the 50s. So is our social problem hiding important information from each other?

Didn’t Harry Harrison cover this long ago:

Deathworld II (The Ethical Engineer) (1964) by Harry Harrison

http://www.magick7.com/1/MoonlightStories/2/012/2027.htm

http://librivox.org/the-ethical-engineer-by-harry-harrison/

Is the genre too much about literature instead of the ideas in the literature? Do too many writers really have nothing to say but merely say it very well?

@24: A person trying to shoehorn in advertising, or a really good spambot? It’s hard to tell these days…