There’s a striking moment near the end of the twenty-first canto of Dante’s Inferno, one that almost all readers tend to remember, when the demon Barbariccia “avea del cul fatto trombetta.” It’s hard to put it delicately: he turns his ass into a trumpet. Not the kind of thing you expect out of a writer recording the steps his salvation, but the image stays with you.

Likewise, readers of the Divine Comedy remember Ugolino, who, for the sin of eating his sons, is forever frozen to his neck in ice, gnawing on the brains of Archbishop Ruggieri. In fact, Dante has no trouble at all depicting sinners in the various postures of their suffering, and for seven centuries readers have kept turning the pages. Corporal violence sells. Electronic Arts even has an eponymously titled video game in which Dante looks less like a poet and more like a Muay Thai Knight Templar. The EA people are no fools—they understand that there’s a ready market for brain eating and ass trumpets.

When it comes to the celestial realm of heaven, however, Dante runs into trouble.

At first blush, this might seem strange; Dante is, after all, a religious poet, and the ascent to heaven is the climax of his spiritual journey. Unfortunately, according to Dante himself: “The passing beyond humanity may not be set forth in words.” (Trans. Singleton)

This is a problem. He is a poet, after all, and poetry tends to rely pretty heavily on words.

So does epic fantasy. Gods are a staple of the genre—old gods, dead gods, newly ascended gods, gods of animals and elves, gods masquerading as goldfish and pollywogs—and with all these gods comes an old, old problem: it is very difficult to describe that which is, by its very nature, beyond description.

There are options, of course, but as each presents challenges, opportunities, and limitations, it’s worth taking a look at them.

Option 1: Leave it out. Just because there are religions and religious characters in a story doesn’t mean we ever need to meet the gods. We don’t tend to be faced in daily life with the full, unspeakable, trans-temporal infinitude of Yahweh or Allah or Vishnu. If we don’t run into the gods in real life, there’s no reason we need to get a good look at their fantasy counterparts, either. I’ve read roughly a bajillion pages of Robert Jordan and Ursula LeGuin’s Earthsea series, and while the gods are sometimes invoked, I haven’t run into one yet (I don’t think).

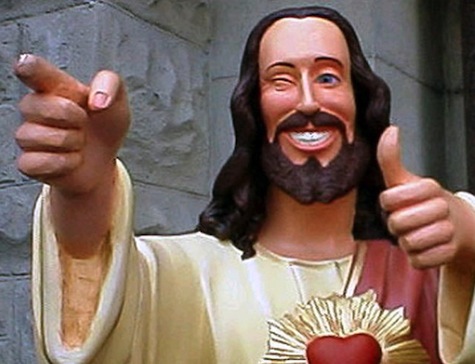

Option 2: Incarnation. The word, at root, means ‘in meat,’ and incarnating the gods of fantasy in human (or bestial) avatars solves a few problems. In extant religion and mythology, gods take human form all the time, usually for one of three reasons: lust (Zeus), instruction and succor (Jesus), or vengeance and punishment (Durga). Ineffable transcendence is all well and good, but sometimes you just can’t beat a nice meaty body, one in which you can move, and love, and fight. Of course, a helpful side benefit of all these cases is that the taking of human form shelters meager mortals from a dangerously unfiltered vision of divinity. It’s also handy as hell if you need to write about gods.

The gods in Steven Erikson’s Malazan series tend to wear meat suits, as they do in Neil Gaiman’s American Gods, and N.K. Jemisin’s The Hundred Thousand Kingdoms. It’s a time honored strategy, one that hearkens back to the Bhagavad Gita (and earlier), when Vishnu takes on the body of Krishna to act as Arjuna’s humble (sort of) charioteer. Of course, Krishna eventually gives Arjuna a glimpse of his true nature, and that brings us to…

Option 3: Go Nuclear. It’s no coincidence that Oppenheimer thought of the Bhagavad Gita after witnessing the detonation of the first atomic bomb. Here’s Vishnu, pulling out the big guns:

“Just remember that I am, and that I support the entire cosmos with only a fragment of my being.”

As he says this, he slips off his human trappings for a moment. Arjuna is suitably impressed:

“O Lord, I see within your body all the gods and every kind of living creature […]You lap the worlds into your burning mouths and swallow them. Filled with your terrible radiance, O Vishnu, the whole of creation bursts into flames.” (Trans. Easwaran)

I find this passage devastatingly effective, but it’s easy to see that an author can’t sustain too many pages like this without developing a reputation for hyperbole.

Option 4: Good Old Metaphor. This is the chosen method of John Milton, no stranger to the struggle to depict the ineffable and divine, who describes his method explicitly in Paradise Lost: “…what surmounts the reach/ Of human sense, I shall delineate so,/ By lik’ning spiritual to corporal forms.”

Various fantasy writers turn this method to good account. R.S. Belcher, in his imaginative debut Six-Gun Tarot, sometimes takes this route. For example, the first time we meet an angel:

“He rode a steed of divine fire across the Fields of Radiance in search of the truant angel […] a proud and beautiful steed whose every stride covered what would one day be known as parsecs.”

This is, of course, shorthand for, “Something-like-a-human-but-better-in-ways-you-can’t-possibly-comprehend did something-like-riding-but-cooler-in-ways-you-can’t-possibly-comprehend on something-like-a-horse-but-faster-and-bigger-in-ways-you-can’t-possibly-comprehend…” etc. I think it’s a quick, elegant solution, and Belcher pulls it off really well in a number of places.

But what if there’s not a handy corporeal likeness for the divine? What about stuff like infinity or godly beneficence or primordial chaos? Are we really supposed to believe that the divine countenance is like unto Jennifer Lawrence’s face? That Las Vegas, shimmering with a million neon signs, is akin to the celestial vault of heaven?

Milton has an answer, but it’s one that shows a good deal more hope than imagination. He suggests that our earthly world might be “but the shadow of Heav’n, and things therein/ Each to other like, more than on earth is thought[.]”

Yeah. That would be handy.

Perhaps more honest, and certainly more extreme is the final option…

Option 5: Gibbering Linguistic Failure. We follow here in the footsteps of Moses Maimonides, the 12th century Jewish Egyptian scholar, who insisted that god can only be described through negation. You can’t say that god is wise or eternal or powerful, because such predicates cannot capture the ineffable essence of divinity. The best one can do is to negate, to carve away all the lousy stuff that god is not: dumb, short, bounded by time, blue-green… whatever. Maimonides got to Dante’s realization about the limits of words more than a century before Dante, and he seems to have taken it more seriously.

Failure here, of course, is success, insofar as the inability to convey the divine through language is, itself, a way of conveying just how divine the divine really is. We can see the approach at work in Belcher again:

“Back when this world was dark water and mud […] back before men, or time, back when all places were one place, this creature lived in the darkness between all the worlds, all the possibilities.”

At first glance, this looks similar to his angel and his horse. On the other hand, the angel and horse, at least, are operating in space and time. In this passage Belcher starts out with metaphor, then quickly throws up his hands. “Never mind,” he says. “You and your puny mortal brain aren’t up to this.”

And I guess we’re not. It’s a hell of a quandary, this depiction of the divine, but I suppose that’s as it should be. After all, if the gods were easy to write about, they wouldn’t be all that epic.

After teaching literature, philosophy, history, and religion for more than a decide, Brian began writing epic fantasy. His first book, The Emperor’s Blades (forthcoming from Tor on January 14, 2014), is the start of his series, Chronicle of the Unhewn Throne. He lives on a steep dirt road in the mountains of southern Vermont, where he divides his time between fathering, writing, husbanding, splitting wood, skiing, and adventuring, not necessarily in that order. He can be found on Twitter at @brianstaveley, Facebook as brianstaveley, and Google+ as Brian Staveley, as well as on his blog.

I think it’s a trap to think of God as only that being that creates the universe, maybe it wasn’t created? Perhaps you are just accepting what these beings claim about themselves?

Seems to me there is plenty of room for god-like beings in the range between speaking from burning bushes, bringing the deluge, or spreading and shaping and guiding life in space.

BTW, what would you consider Sam in Roger Zelazny’s first masterpiece, Lord of Light?

Interesting post. I need to check The Silmarillion etc. to make sure, but I don’t remember a lot of specific description of Eru. I also don’t remember that passage from Dante. My reaction to the few pages of Paradise Lost excerpts in the Norton Anthology that we had to read for class was “Ugn . . . boring! Why do we have to read Milton’s version? We know what happened and the original is a lot shorter!”

Very nice writing of a theme full of pitfalls.

And give Milton a chance, he might surprise you.

Botticelli did an illustrated version of the Divine Comedy and (fortunately) didn’t finish it; the Inferno and Purgatory are completed at sketch level, but Paradise isn’t, and the final Canto, the Empyrean, is illustrated with a completely blank white page and, tiny in the centre, the figures of Christ, the Virgin and St. Lucy. Works well.

http://www.worldofdante.org/gallery_botticelli.html

And this is a constant theme in one SF novel, Paul McAuley’s Renaissancepunk classic “Pasquale’s Angel”.

“O Lord, I see within your body all the gods and every kind of living creature […]You lap the worlds into your burning mouths and swallow them. Filled with your terrible radiance, O Vishnu, the whole of creation bursts into flames.” (Trans. Easwaran)

Maybe it’s just me, but I read this and all I could picture was Rose Tyler at the tail end of the Ninth Doctor’s run. I wonder if any similarities were intentional, subconscious, or just coincidental…

Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite got there a long time before Moses ben Maimon:

“…nor is It any other thing such as we or any other being can have knowledge of; nor does It belong to the category of non-existence or to that of existence; nor do existent beings know It as it actually is, nor does It know them as they actually are; nor can the reason attain to It to name It or to know It; nor is it darkness, nor is It light, or error, or truth; nor can any affirmation or negation apply to it; for while applying affirmations or negations to those orders of being that come next to It, we apply not unto It either affirmation or negation, inasmuch as It transcends all affirmation by being the perfect and unique Cause of all things, and transcends all negation by the pre-eminence of Its simple and absolute nature-free from every limitation and beyond them all.”

My favorite depiction of the divine in fantasy is Lois McMaster Bujold’s gods in her Five Gods series. They are gods who speak to humans, work through humans, love and long after humans, and yet remain unquestionably divine (numinous, even!). They’re also the only gods I’ve come across in fantasy who seem actually worthy of worship. (Come to think of it, Jo Walton and Liz Bourke have had some great posts on these books.)

@8, Check out Jacqueline Carey’s Kushiel series. Alt-Medieval history. Keeps all the pre-Christian religions relevant, changes the events of Christ’s crucifixion, and establishes some fallen angels as gods worth worshipping. It’s an amazing read, the gods have influence but aren’t incarnated, they nudge instead of demand, and their highest command for humankind is, Love as thou wilt.

It is heavy on the eroticism and includes elements of BDSM, so forewarned.

Two quibbles – Earthsea does indeed feature gods of a sort – the ancient Eaters of the Tombs of Atuan, who are all powerful within their limited range.

You also left out the primary means of displaying gods in fantasy – treating them as the unseen (by mortals) masters of a cohort of assistants.

From Angels to Djinn, Efreets to Ghouls, every god worth his salt has an image appropriate henchman or ten, who deal directly with the mortal realm and can have a genre appropriate level of power.

Take the angelic Blessed of Elua as referred to in the Kushiel series above (and the effects of the name of God later in the series).

Contrast with the throw-it-in nature of say Weis & Hickman’s Rose of the Prophet series (which is epic fantasy lite to be fair) where every demonic or spiritous creation is part of an interwoven hierarchy.

In the Malazan series we have Gods, Elder Gods, and Ascendents, and the nebulous nature of exactly what determines which has consumed a fair bit of page space.

And you can’t overlook the classic depiction of Option 5 which has to be the Unspeakable Eldritch Horrors of HP Lovecraft, even if it seldom crops up in Epic Fantasy – most Epic Fantasy is Black vs White, not so much Black vs polkadots

I think that Michael Sullivan’s series handles it well, with a realised mythology, a church made up of good/bad with various shades in between and an interesting deux ex machina.

@3 I do like Milton’s other poems . . . it was just the excerpts of Paradise Lost were so drudgy . . . will have to look for non-drudgy sections!

@12: Dr. Cox — if you want non-drudgy Paradise Lost sections, try books 5 and 6, which depict the war in heaven. That might give you enough of a taste to go back and read the whole thing, which is glorious.

@12 – try books 5 and 6–the War in Heaven is about as non-drudgy as you can get (though if you liked Paradise Regained, I’m not sure how you can think anything in Paradise Lost is drudgy). But really, the poem is much, much better simply by not being excerpted. It’s glorious.

Rick Lockwood@1 makes a good point: in monotheism the god creates the universe, but in a polytheism the universe tends to generate the gods. They are powerful but not infinite. They may be moral forces or amoral ones. But their sphere (what they’re the god of) helps narrow down the embodiment (or the set of embodiments) that suits any particular god in question.

How to get from this kind of skeleton to the awe appropriate to a god… well, that’s the tricky part, I guess. We mostly have our own sense of what is awesome and awful to guide us, and not much else.

Typhon and Scylla and the rest of the Nine in Wolfe’s generation ship series The Long Sun are particularly powerful and mysterious gods within the realm of the ship. AI eidolons of the family of rulers that launched the ship eons ago, showing up on the remaining undamaged viewscreens that have been converted to temples and demanding sacrifice, possessing the ocupants by entering through the eyes.

@7

Thank you for introducing me to Pseudo Dionysius and pricking my curiosity enough to get me to start researching not only all of his theses but also that entire period of Christian religious development.

@15: My guess would be that it came mostly down to real life experience: you better bow done before your king, emperor, whatnot, or you get ground into dust by his minions – now imagine what a being can do to you that cannot be ordered around by said king, and is even capable of putting him down (like whoever controls the thunderstorms, e.g. Zeus) – you make certain to give your obeisance to that guy, as well.