There’s a particular kind of nostalgia that smells like burning autumn leaves on an overcast day. It sounds like a static-filled radio station playing Brylcreem advertisements in the other room. It feels like a scratchy wool blanket. It looks like a wood-paneled library stuffed with leather-bound books.

This is the flavor of occult nostalgia conjured up by author John Bellairs and his illustrator, Edward Gorey, in their middle grade gothic New Zebedee books featuring low-key poker-playing wizards, portents of the apocalypse, gloomy weather, and some of the most complicated names this side of the list of ingredients on a packet of Twinkies.

To a purist, there are really only three New Zebedee books that count: The House with a Clock in Its Walls (1973), The Figure in the Shadows (1975), and The Letter, the Witch, and the Ring (1976). After that, it would be 1993 before another New Zebedee book appeared, and this one would be authored by Brad Strickland based on an unfinished manuscript by Bellairs, who left behind two unfinished manuscripts and two one-page outlines that would become the next three New Zebedee books. Ultimately, the series would total twelve volumes, but the first is the one that captured lightning in a bottle and is, as far as I’m concerned, the only one that counts.

Wracked with high gothic weather, lonely, elliptical, and suffused with a sense of a damp and creeping doom, The House with a Clock in Its Walls is set in 1948 and it begins with fat little Lewis Barnavelt arriving in the town of New Zebedee, MI. Unpopular, unable to swim, bad at sports, and obsessed with the dustiest history imaginable (some of Lewis’s favorite books are the lectures of John L. Stoddard), Lewis’s parents died in a car accident and he’s been sent to live with his uncle Jonathan Barnavelt in New Zebedee, a town, we are told, in which crazy people are constantly escaping from the Kalamazoo Mental Hospital and jumping out naked from behind trees. After arriving, Lewis never mentions his parents again, and why would he? Not only is Jonathan an awesome bachelor who plays poker with kids, doesn’t give them bedtimes, and has a Victorian house full of hidden passages and dusty unused rooms, but his BFF, Mrs. Zimmerman, lives next door, just on the other side of a secret tunnel, and the two of them while away their time competing in obscure card games and lobbing insults like “Brush Mug” and “Hag Face” at each another.

Even better, Johnathan and Mrs. Zimmerman are wizards, expert in a particularly laidback kind of magic: the stained glass windows in Jonathan’s house change scenes randomly, the Wurlitzer plays the local radio station (advertisements included), during the Christmas holidays Jonathan conjures up the Fuse Box Dwarf (who leaps out and says “Dreeb! Dreeb! I am the Fuse Box Dwarf.”) and, when pressed, they can cause a lunar eclipse. Although the magic is delivered with all the matter-of-fact attitude of a bus transfer, it is the magician who owned the house before them, Isaac Izard—whom they regard as a bit of a tightass—who hid a clock somewhere in its walls that’s ticking down the time to a particularly New Englandy, Protestanty sounding doomsday. Jonathan wants to find and destroy the clock, although more as a hobby than an actual race against time, but first there’s milk and cookies and games of Five-Card Stud to be played. It’s not until Lewis, in an attempt to impress Tarby, his only friend at school, raises Izard’s wife from the dead that things take on a sense of panic and desperation.

House is a book obsessed with magic, and it adheres to the classic rule of magic in its structure. It uses misdirection to obscure what’s important, giving enormous page-time to extraneous details like a lunar eclipse party or Lewis’s birthday illusion of the Spanish Armada, while barely mentioning the actual impending apocalypse. The result is that it leaves a lot unsaid, indicated by insinuation, hinting at What Might Happen in dark whispers, and thus all the more intriguing. For a middle grade reader it’s what adults say sotto voce or behind their bedroom doors that’s so interesting, and so House dishes up a delightfully banal magic with one hand, while tantalizing the reader by keeping the darkest things just out of sight with the other.

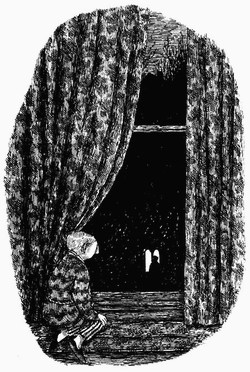

Bellairs loved M.R. James and, accordingly, this is a book that is fueled by unsolvable mysteries, both important and un-. What exactly is the relationship between Jonathan and Mrs. Zimmerman? Why does Izard want to destroy the world? How is he actually going to do it? How powerful is his reanimated wife? What does he look like? Edward Gorey’s scratchy, doom-laden, slightly disreputable illustrations keep the game alive, showing us Izard’s reanimated wife only as a pair of burning, silver discs that we assume are her eyes. Bellairs and Gorey are possessed of either a demure gentility or an insidious intelligence. When we’re told that a character has gone missing and then presented with the information that the blood of a hanged man is necessary for Izard’s end times ritual, our own imaginations leap eagerly to fill in the gaps with gruesome, gothic invention.

House was originally intended as an adult novel, but the second editor who read it suggested Bellairs re-write it as middle-grade, thus launching Bellair’s career as a young adult author. But the book has a maturity to it, and a painful spikiness around its feelings, that is a hallmark of the best YA and middle-grade fiction. Lewis is a loser, and he never gets to triumph over incredible odds, or save the day. His relationship with Tarby, a popular kid only hanging out with Lewis while his broken arm mends, is decidedly authentic. Tarby makes fun of Lewis’s belief in magic, but both times Lewis shows him real magic Tarby rejects him harshly and immediately.

Next came The Figure in the Shadows. Now that Bellairs was writing middle grade from scratch and not repurposing an adult manuscript, the writing feels condescending. Characters refer to each other repeatedly by their full names in the first few pages so that young readers can better remember them. What worked in the first book (a dark figure approaching at night, a headlong car journey) is deployed again for lesser effect. Rose Rita, a tomboy and Lewis’s only friend, is added to the mix and the tensions between the two of them add some spice, but by the end of the book one is left feeling a little bit like we’ve been here before, and last time we were wearing more sophisticated clothes. It’s not bad, but it doesn’t quite match the original.

The third book is clearly suffering from exhaustion. The Letter, the Witch, and the Ring is another story, like Figure, that revolves around a magical item. This time, Mrs. Zimmerman and Rose Rita hit the road in search of a magic ring while Lewis goes to Boy Scout camp in an attempt to man up and impress Rose Rita. There is a lot of wheel-spinning in this book, and the plot is so simple that I remember being bored by it even when I first read it at nine years old. The only character introduced besides the two main characters turns out to be a witch who fits all the stereotypes (unlucky in love, old, bitter, jealous). It is, all in all, a flat note to end on for these first three books.

Then again, there is one moment that recaptures the magic of the first book. Rose Rita is desperate not to grow up and have to wear dresses and go to parties and leave Lewis behind. The climax of Witch finds her running, out of her mind, through the woods, magic ring in hand, desperate to conjure up a demon and demand that her wish be granted. We’re not told what she’ll wish for, but it’s obvious: she never wants to grow up. Equally obvious is the knowledge that this will not end well for her. But there is no one to stop her. It’s a long passage, and one that’s written in a heightened state of demented hysteria that feels uncomfortable, deeply felt, and possessed by real passion.

Bellairs went on to write many more young adult books, including the Anthony Monday series and more New Zebedee books, but for several generations of readers he is known for his first book, The House with a Clock in Its Walls and its two sequels of diminishing returns. House, with its mid-century aura of gothic Americana is unforgettable for the oblique glimpses it offered kids of the unseen, the unknowable, the occult, and, most importantly, the adult.

Grady Hendrix is the author of Satan Loves You, Occupy Space, and he’s the co-author of Dirt Candy: A Cookbook, the first graphic novel cookbook. He’s written for publications ranging from Playboy to World Literature Today and his story, “Mofongo Knows” appears in the anthology, The Mad Scientist’s Guide to World Domination.

Great read – this takes me back.

I was also a fan of (most of) his Johnny Dixon books, though I haven’t re-read him lately to see how they hold up.

I did not realize there are 9 more non-Bellairs books. I am wondering if it’s worth checking those out. I loved The House with the Clock in its Walls, but I suspect it might not strike the same chord with a modern audience.

@3 – The first three posthumous books were planned and drafted/outlined a bit by Bellairs, and the first two are particularly great. If you like the first 3 books, definitely check out The Ghost in the Mirror and The Vengeance of the Witch-Finder. I read the whole series and enjoyed them all to some degree, but those two are essential reading for fans of Lewis Barnevelt and friends.

I love this series so much – we even took a road trip in college to go see the house that Bellairs based the book on!

I may have to go read the Rose Rita book again – I remember thinking her wish was going to be to turn into a boy, not to not grow up. And that always annoyed me, since it was the one book about a girl and the only thing he could think of for her to want was to not be a girl? Grrrr.

This does remind me that I really need to pick up House and The Curse of the Blue Figurine for my kids. Though they’re only six months old, so I have time yet.

Rose Rita’s wish in TLTWATR is to be a boy! Not to never grow up. As a female reader, that’s what was obvious to me!

This is one of my favorite childhood books – I had nightmares about the silver reflections from Izard’s dead wife’s glasses… and while I know I read the sequels, I remember them not.

But HWACITW. I haven’t read it in years, and still remember parts with crystal clarity. The clock-winding strangeness Uncle Jonathan shows early. The Spanish Armada vision. The highly creepy car chase, where they foil Mrs. Izard by crossing running water. The Hand of Glory. The broken glasses at the end. The perfect match of creepy words and creepy pictures.

I’ve been meaning to read House With A Clock again.

The other Bellairs book I remember liking was The Face in the Frost. That one was supposedly for an older audience but many of the ingredients are the same (low key unheroic protagonists, evil wizard trying to end the world, creepy atmosphere.)

As several others have said, I’m fairly sure Rose Rita’s wish in TLTWATR was to be a boy… But you’re interpretation is actually substantively correct; RR sees boyhood as a way to avoid the travails of female adolescence, (cotillion, dating, all the trappings of young womanhood in fact) and thus by wishing to become a boy she is, in essence, wishing for an eternal childhood of climbing trees, playing flies & grounders, and ignoring the gender divide which threatens to either complicate or otherwise change the innocence of her friendship with Lewis.

Speaking of Bellairs and the Lewis Barnavelt stories, I was perusing my local antique store / junk shop yesterday, and what do you think I stumbled upon?

An 1898 copy of John L. Stoddard’s Lectures. The store only had the one book out of Stoddard’s entire Lectures series, and I bought it for $5.

Guess which volume?

Number 9. I shivered. Faded gilt lettering on a worn black buckram spine. Just as decribed!

I like to think Lewis would have approved of my purchase. :)

It’s funny – I never thought Rose Rita’s wish was to be a boy or to not grow up. I kind of thought she wanted basically the same thing that Gert wanted: to become the opposite of what she was perceived to be (a stereotypically attractive girl/woman), since there was so much emphasis in the books about her being a nerdy tomboy. I mean, I can see where turning into a boy or not growing up would solve the problem too, but that was not my take.

Why are some of these books so expensive to buy? I had to buy the second and third in ebook form so I could afford them. I read the first, then the fourth (ghost in mirror) because I didn’t know the correct order.

What is the correct order of the entire Barnavelt series?

I collect books and would love to have the entire set for my students and grandchildren to read, but I just wondered why they were so expensive.