One of the core reasons I make books now is because Ray Bradbury scared me so happy, that what I am perpetually compelled to do is, at best, ignite the same flame in a young reader today. Most of my comics, certainly the ones I write myself, are scary ones or revolve around scary themes. In the last ten years I began to notice that they also featured, as protagonists, children. Even when the overall story wasn’t necessarily about them, there they were: peeking from behind some safe remove, watching.

I came to understand the pattern was leading me to a more clearly defined ethos when I both had kids of my own and I came to find that the comics industry had for the most part decided not to make books for kids anymore. Instead they wanted to tailor even their brightly colored, undies-on-the-outside superhero books to old men nostalgic for their long-passed childhoods than for the children they were intended to inspire. Insane, right? This generation had not only stolen the medium away from its following generations, it had helped foster one of the greatest publishing face-plants in American history: it killed its own future by ignoring the basic need to grow a new crop of readers, and so made certain it had no future at all.

And one thing no one was going near was horror stories for kids. Clinton was president and we hadn’t yet learned about the wonderful effects anthrax-laced letters, the Washington DC snipers, and everyone losing their jobs would have on us. (To be perfectly honest, I think I—like many others—existed in a continual state of fear from mid-2001 all the way up to last Wednesday). The time has become ripe again and with the collapse of the DC and Marvel models, it was time to do what they wouldn’t: scare the hell out of kids and teach them to love it. Here’s why this is not as crazy as it sounds:

Reason #1: CHILDHOOD IS SCARY

Maurice Sendak, whom I love as a contributor to the lore of children’s literature as well as a dangerous and wily critic of the medium (especially his grouchy latter years), once countered a happy interviewer by demanding she understand that childhood was not a skip-hop through a candy-cane field of butterflies and sharing and sunshine, that is was in fact a terrifying ordeal he felt compelled to help kids survive. Kids live in a world of insane giants already. Nothing is the right size. The doorknobs are too high, the chairs too big… They have little agency of their own, and are barely given the power to even choose their own clothes. (Though no real “power ” can ever be given, anyway… maybe “privilege” is the right term.) Aside from the legitimate fears of every generation, kids today are enjoying seeing these madhouse giants lose their jobs, blow themselves up using the same planes they ride to visit grandma, and catastrophically ruin their own ecosystem, ushering in a new era of unknown tectonic change and loss their grandkids will get to enjoy in full. The insane giants did to the world what they did to comics: they didn’t grow a future, but instead ate it for dinner.

It’s a spooky time to be a kid, even without Sandy Hook making even the once-fortified classroom a potential doomsday ride. Look, the kids are already scared, so let’s give them some tools to cope with it beyond telling them not to worry about it all… when they really have every right to be scared poopless. Scary stories tell kids there’s always something worse, and in effect come across as more honest because they exist in a realm already familiar to them. Scary tales don’t warp kids; they give them a place to blow off steam while they are being warped by everything else.

Reason #2: POWER TO THE POWERLESS

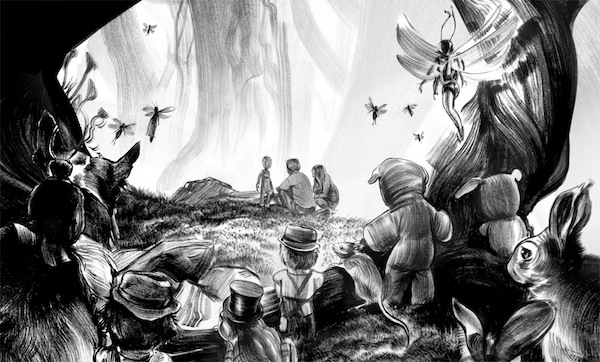

The basic thing horror does for all of us is also its most ancient talent, the favorite system of crowd control invented by the ancient Greeks: catharsis. Who doesn’t walk out of a movie that just scared the pants off of them mercifully comforted by the mundane walk to through the parking lot and the world outside? For kids this is even more acute. If we take it further and make children both the object of terror in these stories as well as agents for surviving the monsters…well, now you’re onto something magical. Plainly put, horror provides a playground in which kids can dance with their fears in a safe way that can teach them how to survive monsters and be powerful, too. Horror for kids lets them not only read or see these terrible beasts, but also see themselves in the stories’ protagonists. The hero’s victory is their victory. The beast is whomever they find beastly in their own lives. A kid finishing a scary book, or movie can walk away having met the monster and survived, ready and better armed against the next villain that will be coming…

Reason #3: HORROR IS ANCIENT AND REAL AND CAN TEACH US MUCH

In the old days, fairy tales and stories for kids were designed to teach them to avoid places of danger, strangers, and weird old ladies living in candy-covered houses. They were cautionary tales for generations of kids who faced death, real and tangible, almost each and every day. There was a real and preventive purpose to these stories: stay alive and watch out for the myriad of real world threats that haunt your every step. These stories, of course, were terrifying, but these were also children that grew up in a time where, of every six kids born, two or three would survive to adulthood. Go and read some of the original Oz books by Baum and tell me they are not freakishly weird and threatening. The Brothers Grimm sought to warn kids in the most horrifying way they could. So much so that these types of tales have all but vanished from children’s lit, because these days they are deemed too frightening and dark for them. But they also are now more anecdotal than they were then; they mean less because the world around them grew and changed and they remained as they had always been. They became less relevant, however fantastic and crazy-pants they are.

Horror also touches something deep within us, right down into our fight-or-flight responses. We have developed, as a species, from an evolutionary necessity to be afraid of threats so we might flee them and survive to make more babies that can grow up to be suitably afraid of threats, that can also grow up and repeat the cycle. We exist today because of these smart apes and they deserve our thanks for learning that lesson. As a result, like almost all pop culture, horror lit can reflect in a unique way the extremely scary difficulties of being a child in a certain time. It touches on something we all feel and are familiar with, and as such can reveal a deeper understanding of ourselves as we go through the arc of being scared, then relieved, and then scared again. The thrill is an ancient one, and when we feel it, we’re connecting with something old and powerful within us. Whether it’s a roller-coaster, a steep water slide, or watching Harry Potter choke down a golden snitch as he falls thirty stories from his witch’s broom. There is a universality in vicarious thrill-seeking and danger-hunting. It is us touching they who began the cycle forty thousand years past.

Reason #4: HORROR CONFIRMS SECRET TRUTHS

“You know when grown-ups tell you everything’s going to be fine and there’s nothing to be worried about, but you know they’re lying? ” says the Doctor of a young, mortified Amy Pond. “Uh-huh ,” she replies, rolling her ten-year-old eyes dramatically. The Doctor leans in, a wink in his eye and intimates… “Everything’s going to be fine.” And then they turn to face the monster living in her wall with a screwdriver in one hand and a half eaten apple in the other.

In doing this, Moffat touches brilliantly upon another essential truth of horror—that it shows us guardians and guides that will be more honest with us than even our own parents. Within the darkness and shadows is our guide, who can lead us out and back into the light, but you can only find him there in the darkness, when you need him most. Kids are aware of so much more that’s happening in their house than we as parents even want to imagine. But because we don’t share all the details of our anxious whispers, stressful phone calls, or hushed arguments, (and rightfully so), they are left to fill in the facts themselves, and what one imagines tends to be far more terrible than what is real. They know you’re fighting about something, but not what. They can tell what hastened whispers in the hall mean outside their door… or they think they do. And what they don’t know for a fact, they fill in with fictions. Storytellers dabbling in horror provide them with an honest broker who doesn’t shy away from the fact of werewolves or face-eating aliens that want to put their insect babies in our stomachs. They look you straight into their eyes and whisper delightfully “Everything’s going to be fine.” The mere fact of telling these tales proves a willingness to join in with kids in their nightmares, bring them to life, and then subvert and vanquish them. Children love you for this, because you are sharing a secret with them they don’t yet realize everyone else also knows: this is fun.

The end result, for me, at least was a great sense of trust in scary movies I never got from my parents, who tried to comfort me by telling me ghosts weren’t real. Horror told me they were, but it also taught me how to face them. We deny to our kids the full measure of what we experience and suffer as adults, but they aren’t idiots and know something’s going on, and what we’re really doing by accident is robbing them of the trust that they can survive, and that we understand this and can help them to do so. Where we as adults cannot tell them a half-truth, horror can tell them the whole, and there is a great mercy in that.

Reason #5: SHARING SCARY STORIES BRINGS PEOPLE TOGETHER

How many times have I seen a group of kids discover to their excessive delight that they have all read and loved the same Goosebumps book? A LOT. The first thing they do is compare and rank the scariest parts and laugh at how they jumped out of their bed when the cat came for a pat on the head, or stayed up all night staring at the half open closet. Like vets having shared a battle, they are brought together in something far more essential and primordial than a mere soccer game or a surprise math test. And looking back myself, I cannot recall having more fun in a movie theater or at home with illicit late night cable tv, than when I was watching a scary movie with my friends. The shared experience, the screams and adrenaline-induced laughter that always follow are some of the best and least fraught times in childhood. And going through it together means we aren’t alone anymore. Not really.

Reason #6: HIDDEN INSIDE HORROR ARE THE FACTS OF LIFE

Growing up is scary and painful, and violent, and your body is doing weird things and you might, to your great horror, become something beastly and terrible on the other side. (The Wolfman taught us this). Being weird can be lonely and your parents never understand you and the world is sometimes incomprehensible. (Just as Frankenstein’s monster showed us). Sex and desire is creepy and intimate in dangerous and potentially threatening ways (so sayeth Dracula).

Whether it’s The Hunger Games as a clear cut metaphor for the Darwinian hellscape of highschool, or learning to turn and face a scary part of ourselves, or the dangers of the past via any of the zillions of ghost stories around, horror can serve as a thinly-veiled reflection of ourselves in a way almost impossible to imagine in other forms. Horror can do this because, like sci-fi and fantasy, it has inherent within it a cloak of genre tropes that beg to be stripped off. Its treasures are never buried so deep that you can’t find them with some mild digging. It’s a gift to us made better by having to root around for it, and like all deep knowledge, we must earn its boons rather than receive them, guppy-mouthed, like babies on a bottle.

Fear is not the best thing in the world, of course, but it’s not going anywhere and we are likely forced to meet it in some capacity, great or small, each and every day. There’s no way around it. Denying this fact only provides more fertile ground for fear to take root. Worse yet, denying it robs us of our agency to meet and overcome it. The more we ignore scary things, the bigger and scarier those things become. One of the great truths from Herbert’s perpetually important Dune series is the Bene Gesserit’s Litany Against Fear:

I must not fear.

Fear is the mind-killer.

Fear is the little death that brings total obliteration.

I will face my fear.

I will permit it to pass over me and through me.

And when it is gone past I will turn to see its path.

Where the fear has gone, there will be nothing.

Only I will remain.

In so many geeky ways this sums up the most important and primary element of fear—not to pretend that it doesn’t exist, or whether it should or not, but to meet it, to hug it, and to let it go so we may be better prepared for whatever else comes next. Crafting horror narratives for kids does require changing the way scary things are approached, but I would argue that what tools we are required to take off the table for a younger audience aren’t really important tools in telling those stories in the first place. Rape, gore, and splatter themes are terrible, deeply lazy and often poorly executed shortcuts for delivering weight and fear in a story. Losing them and being forced to employ more elegant and successful tools, like mood, pacing, and off-camera violence—the sorts of things one must do to make scary stories for kids—make these tales more interesting and qualitative, anyway. We are forced to think more creatively when we are denied the alluring tropes of the genre to lean on. We are more apt to reinvent the genre when we aren’t burdened by the rules all genres lure us into adopting. With kids, one must land on safer ground sooner than would be the case with adults, but otherwise what I do as a writer when I tell a scary story to kids is essentially the same thing I would do to craft one for adults. There are certain themes that require life experience to understand as a reader, as well, and a successful storyteller should know their audience.

Don’t be afraid to scare your kids, or your kids’ friends, with scary books you love. Obviously you have to tailor things to your kids’ individual levels. For example, films and books I let my 11-year-old digest, I won’t let my younger boy get into until he’s 14. They’re just different people and can handle different levels of material. They both love spooky stuff, but within their individual limits. Showing The Shining to an 8-year-old is generally a poor idea, so my advice is when there’s doubt, leave it out. You can’t make anyone un-see what you show them, and you should be responsible as to what they are exposed to. I’m a bit nostalgic about sneaking into to see The Exorcist at the dollar cinema way too young, but I also remember what it felt like to wake up with twisty-headed nightmares for a month afterward, too. Being scared and being terrorized are not the same thing. Know the difference and don’t cross the streams or it will totally backfire on you. But if you navigate it right, it can be a completely positive and powerful experience.

So get out there and scare some kids today! Do it right and they’ll thank you when they’re older. There will be a lot of adults who find this whole post offensive and terrible, even as their kids cry for the material… I remind them that children are often smarter than the adults they wind up becoming. The parents that find this so inappropriate are under the illusion that if they don’t ever let their kids know any of this stuff, they won’t have bad dreams or be afraid—not knowing that, tragically, they are just making them more vulnerable to fear. Let the kids follow their interests, but be a good guardian rather than an oppressive guard. Only adults are under the delusion that childhood is a fairy rainbow fantasy land: just let your kids lead on what they love, and you’ll be fine.

All images by Greg Ruth.

The article originally appeared May 23, 2014, on Muddy Colors.

Greg Ruth has been working in comics since 1993 and has published work for The New York Times, DC Comics, Paradox Press, Fantagraphics Books, Caliber Comics, Dark Horse Comics and The Matrix. He has shown his paintings in New York, Houston, and Baltimore, and he also exhibited a series of murals at New York’s Grand Central Terminal in 2002.

Great essay, and one I wish more people would take to heart. Also reminds me of this:

Can someone let me know where the third picture is from? Amazing art.

@2 – All the illustrations are by Greg Ruth, who has illustrated many stories here on Tor.com. I’m not sure where the third picture is from, but here’s Greg’s website and here’s a gallery of his works for Tor.com – maybe you can find it there.

“Only adults are under the delusion that childhood is a fairy rainbow fantasy land, just let your kids lead on what they love, and you’ll be fine.”

Raising kids of my own, I have come to realize how much the rainbow fanstasy land, let’s-protect-our-kids-from-everything mentality hurts. I want my kids to be able to see the bad, know their abilities, and stand against whatever life brings. I will not be there to bail them out (well, not always) as adults. I love reading to my kids and discussing with them their own abilities and aptitudes hopefully to prepare them for challenges in life.

Scary monster stories and suspenseful situations teach so much when the guide (the narrator or me, as a parent) is there to shine the hope into the gloom, show the path, and let my kids learn how to make the choice on their own to take it.

Great essay, btw, Greg. I will look for your work.

I volunteer at the elementary school library, and all I hear from the kids (K-6) is “Where are the scary books? Do you have books about zombies? I want mummies. I want vampires.”

Once they have finished our collection of Goosebumps and the books by Robert San Souci, I am pretty much out of things to give them. Even the 5-year-olds don’t want happy, cute monsters. They want picture books of terror.

They are hard to scare, too. Books that terrified me when I was a kid don’t even register as scary to them: Alice in Wonderland, anything by Roald Dahl, Narnia. (Actually, I didn’t and don’t like those stories, but I still think they are scary.) If I recommend those in response to the endless demand for monsters, they just roll their eyes at me.

So, if anyone has any good suggestions for horror, especially at a very beginning reading level, I will go buy a collection for my local school. I just don’t know where to start.

So, because I disagree with you, I must be a bad parent? Dooming my child to being completely unable to adapt to fear, because I don’t want them to be inundated with horror, when enough exists already on CNN?

Because children read these books does not somehow prepare them for anything. Having someone who they can talk to, be that friends/parents/whomever, is the key.

I’ve read these classic fairy tales and horror stories of monsters, I was forced to read Bridge To Terabithia and Flight of the BumbleBee and other horrible crap. None of that helped me in the least become capable of dealing with fear and loss, except to realize in shock that these things actually happen and are *so much worse* than the books.

Life itself does enough to scare and kill us, there is no need to seek that out.

I think you’re equating horror with truth, and while I believe you must be truthful with children I don’t think that means you should set out trying to scare them. I have no kids, but speaking from my memories as a child, there are some people, books, movies that set out to scare me and scarred (and scared) me for life. They weren’t showing me truths but lies that I was too young to distinguish the difference between on my own. They made it so I could not sleep without lights, so I could not sleep period without nightmares that made me wake screaming. Some of those fears still haunt me today, decades later, in a very real way.

If your kids want it, great. But remember that it can cause harm as well for children with strong imaginations.

I am pretty sure the reason why I’ve never had a scary dream is because I got started on fantasy as a kid, and even scary books couldn’t get to me after that. In every dream I’ve had where there has been danger, I am not in danger myself. Mom read us the less sanitized version of the fairy tales as well.

I bought my god daughter a really neatly illustrated collection of fairy tale comics, they had everything from Red Riding Hood to Cinderalla and whatnot. Her Dad won’t give them to her though (she’s 4 but reads really well), because he thinks they are too scary. Ah well, another sanitized child.

Thanks everyone for your kind and thoughtful responses. It’s a tricky subject but one I think ell worth discussing. I’m very gratified to hear it’s sentiments are echoed here so dilligently. Kids are the best of guides in this and many things, and I continue to press the notion we should, in this realm in particular, let them lead. Scary stories are not for everyone, and those who don’t want to go there should never be forced to. I could say the same for romance, Fantasy, Sci-fi and even religion. We are shepherds of pre-adults, not their owners, and our role isn’t to program them but to make them open to the world, and find joy wherever they can, in whatever form it takes. I take great joy int hese stories and It’s great to hear most of you do as well.

As for the current dissent… No of course not. I make no judgements as to the quality of your parenting skills. My wife disagrees with me daily and she’s an awesome parent. I think what you’re disagreeing with isn’t what I’m saying- I would never call for inundating any kid with horror or any one thing, nor do I. I think the conversation and the experience of the material is the key- as is not being afraid to give kids credit enough to digest and by proxy, come to develop tools for dealing with scary things. CNN is real life terror, what I’m trying to support here is an advocacy for the imaginary realms of spooky stories. There is a humongous difference. Again, the goal is not to terrorize. I’m not sure you understood the point I was making- I’m not trying to goad you into a fight, but I defend my thesis completely and don’t think this is a response to that thesis exactly, but to another subject altogether.

And for the record I thought Bridge To Terribithia was lovely. I don’t know how I would call it horror, but rather tragic. But to return to your initial perspective, because I prefer a certain outlook or book, or film doesn’t mean you must or have to or should. I don’t deal in extremes. I’m sorry you were forced to read a novel that bothered you so much. But perhaps look at it as a challenge. We grow from such digressions and uncertain places.

It’s hard to write about what’s good for children because every child is different, but in general I agree with this essay.

In short, the imagination is a scary place, but worth fully exploring.

If not for trying to protect one’s child from everything, how would Buddhism have got started?

You’ve done a good job explaining not only why scary stories are good for kids, but also why I like ghost-, monster-, or otherwise supernatural-based horror movies and not the Saw-like serial killer or torturer variety of horror movies.

Give me a ghost or monster I can run away from, or defeat, not a guy with a gun or blade who really might exist. The former, when well done, makes me walk away feeling like life is manageable and the mundane worth appreciating. The latter just makes me ill, since it’s all too real.

@Difficat

Coraline and The Graveyard Book by Neil Gaiman are good places to start (although they are quite well-known, so perhaps you’ve already tried them).

For older kids, I’ve also heard great things about The Monstrumologist books by Rick Yancey. I’ve never read them, but they are always shelved as horror in my library.

It surprises me that kids don’t find Roald Dahl scary. The Witches remains, to this day, the book that scared me the most of any that I’ve ever read.

Perhaps I did misunderstand your thesis, perhaps you can help me through it again? I am genuinely interested in your premise, if it means that I should change my mind about what to expose my progeny to. I’ll paraphrase your points as I understand them, and then my reaction:

1 – Childhood is Scary / kids are already scared, so give them something scarier to show them that it can always get worse

Hm, I think that sounds like an “in my day we walked uphill both ways in the snow” sort of idea, but I’ll accept that childhood is scary. Doesn’t seem like we need to belittle whatever the child is currently scared of by doing so (not directly what you meant to do, but I think possible if we’re just trying to one-up their current problem)

2 – Power to the Powerless / catharsis. by resolving the horror in the story, providing a hero, we’re showing that the fear can be beaten

First, the Greeks were idiots, catharsis is only good if you’ve not actually experienced something, otherwise you’re dredging up old feelings, not getting rid of anything. There, I’m done with that ad hominem attack. Stupid Greeks. And stupid Disney for buying into “catharsis”.

“Showing the fear can be beaten” part – This is the fallacy I see that I was addressing in my last post, that real life things can’t always be beaten. Life isn’t fair, it’s hard and can be horrible, and the only way to deal with that particular fun fact is to find coping mechanisms with family, friends, society. But that lesson cannot (and maybe should not) be taught to children through literature. They will inexorably experience this in their life at some point. That Dracula was staked through the heart is not as powerful (to me) as reading about Travis Miller, quadruple amputee, because one is completely abstract and open to interpretation, the other is real and inspiring.

3 – Horror is ancient and real and can teach us much / fairy tales were scary. Apes. Vicarious insight into evolutionarily embedded fear.

What part of this can “teach us much”? I understand you enjoy it, so you think it’s fun, but I’m missing the part where introducing new fears on top of real evolutionarily embedded fears like pain and death, is helpful?

4 – Horror confirms secret truths / parents are lying to you. Honestly, this part confuses me, so I’m not going to try paraphrasing it.

I get that you think it’s fun, but you say several things here. One, that you think it’s fun, and that by telling the tales to kids, you’re sharing that fun with them. Ok, great, but what if I don’t think it’s fun? I’m just sharing my alarm with them, since they can read me better than just what I’m saying.

Next, “Storytellers dabbling in horror provide them with an honest broker who doesn’t shy away from the fact of werewolves or face-eating aliens that want to put their insect babies in our stomachs.” And then “The end result for me at least was a great sense of trust in scary movies I never got from my parents who tried to comfort me by telling me ghosts weren’t real. Horror told me they were, but it taught me how to face them.” So, help me here. You think we shouldn’t hide things from our children, because they’ll just imagine worse that what we’re hiding, got that. The rest, sounds like you’re confused, and that the stories were lying when your parents were telling the truth? But you decided to believe the stories instead? I’m just not sure what the “secret truth” is when it’s not true?

5 – Sharing scary stories brings people together

Well, no, shared experience brings people together, doesn’t have to be horror. Which is a point we have in common, that finding a shared experience is what helps people get through traumatic events, on whatever scale. Then you say this, which is entirely too flippant for my taste: “Like vets having shared a battle they are brought together in something far more essential and primordial than a mere soccer game or a surprise math test.” First, see my point about catharsis, the fact that it’s more than soccer or math is because they haven’t experienced anything like it. Second, “like vets having shared a battle”? Horror stories for children are like vets sharing a battle? For shame.

6 – inside the horror are the facts of life / Wolfman = puberty is terrifying, Frankenstein’s monster = your parents never understand you and life is incomprehensible, Dracula = sex is wierd and scary and dangerous.

Well, all three of those monster morals you listed seem like exactly what I do NOT want my children to feel.

Lastly, in your response you said “CNN is real life terror, what I’m trying to support here is an advocacy for the imaginary realms of spooky stories. There is a humongous difference.”

Are you saying then that your thesis is that you are in support of imagination in general as a way to deal with fear? If so, then we agree. However, I’m not sure I actually read that in your post, since it seems that horror stories might simply be fun for you, but not particularly helpful in practical application to life? (See shellywb’s post)

As for the Bridge To Terebithia part, that’s the worst part of it, I wasn’t forced to read it. Well, it was on the school curriculum, so I suppose I was, but I loved it as a kid. Same with Flight of the Bumblebee. But now, having experienced loss and things out of my control (and not nearly as much as a myriad of other people I know, so I can’t imagine how they feel), I cannot believe that these books are foisted upon children. I do not see the point anymore. and I don’t know how I am going to react when I find out my children are going to be asked to read them. At this point, tragedy = horror for me, because it is real life horror.

@opinionated, I am pretty sure nothing in here said “bad parent.” Not every kid is the same. I hated all scary stories when I was a kid, and to this day I usually avoid them because I get nightmares and/or they make me unhappy. So I didn’t read them. Or watch the movies. (My one exception is Magic by William Goldman, which is horror and I loved it.)

My daughter, on the other hand, wrote her own zombie story when she was about 5, and doesn’t seem to find very many things scary, except the Vashta Narada. Even the Nazgul didn’t bother her. Still, we are careful to limit her to things we think she can handle.

It isn’t like there is one way to parent, or that the same books are good for every child. Children should read whatever they want, whether it is comics, horror, princesses, or biography. But from my experience in the school library, what a lot of them want is definitely horror. And the lack of available titles for me to give them is largely due to adults thinking that horror is always bad for kids. That is a very common view and I love that this article addresses that very belief.

@ballisticjaguar, I would find a ballistic jaguar to be very frightening indeed. And thanks for the suggestions.

One of the best articles about horror I’ve ever read. Right up there with anything Uncle Stevie wrote in Danse Macabre. HOWEVER, can you guys please hire a good proofreader? Typos galore.

@16 – Moderator here. I’ll read through the article and forward suggestions to the Tor.com staff. Thanks!

Mr. Ruth, this is an excellent essay. May I recommend to your attention the book “Killing Monsters: Why Children Need Fantasy, Super Heroes and Make Believe Violence” by Gerald Jones, 2002. It covers a lot of the same territory. The author does an unusually good job of combining the prespectives of parent and story teller.

Ray Bradbury wrote a number of creepy things, from some of his short stories (“Uncle Einar has Green Wings”) to novellas (“The Halloween Tree”) to the seminal Something Wicked This Way Comes. Give your preteen a taste test of some of them.

Thanks again everyone- Apologies if I can’t respond to everyone’s points on both sides. Will try to do my best. (And will definitely be tracking down that book, JohnnyMac- thanks)

Ray Bradbury is why I fell in love with books. I got a hold of his massive short stories collection when I was very young and haven’t stopped since. His ability to combine scary and joyful in a single story… just stunning. Something Wicked This Way Comes still stries my soul.

Difficat @5, I will offer a couple of suggestions:

First, the “Green Knowe” series by L. M. Boston. The Green Knowe of the titles is an ancient English house. The adventures of various children living there range from the eerie to the terrifying. At the high end of the scary scale is “An Enemy at Green Knowe”, which gave me a good set of nightmares when I first read it at the age of 10 or so.

Second, a good collection of the spooky stories of Robert Westall.

Finally, if you can find a copy, Avram Davidson’s “The Boss in the Wall”. Don’t read this if you are home alone, especially in an older house given to odd creaking and rustling noises in the dark hours.

The Bradbury book I would always recommend,a side from all of them, is the giant time, THE STORIES OF RAY BRADBURY. I also quite liked THE HOUSE WITH A CLOCK IN ITS WALLS for young readers as well.

And if you’re interested to learn more, and see what I’m talking about in a filmic way, there is Ben tobin’s really excellent short documentary on meow self entitled, THE DRYBRUSH MASTER. YOu can see it free and in HD right now at the link below:

http://vimeo.com/90784758

Keep the suggestions and conversations going. I love these book recommendations especially. Feel like my post needed a whole index of possibles, and glad to see one forming here.

G

Oh how could I ever forget… PRINCE OMBRA! Really stunning book about a quiet frail boy who has to learn to be brave and battle his own nemesis for the sake of us all. Great mythology and human character. Just a perfect novel. Always wanted to adapt it into comics one day. Still do I guess.

It’s important to face one’s fears rather than hide but I’m not convinced we should potentially add to our childrens’ fears in the process of trying to teach that lesson, especially if the new fears will be irrational.

Children don’t appreciate metaphor like adults do. They take their lessons (along with everything else) more literally. A story about facing monsters may not translate into “I can face my bully in the schoolyard”. It may very well remain, “I need to watch out for supernatural monsters.” Their nightmares attest to this.

Alternative options exist for learning to overcome fear, even to find entertainment in doing so. I vote for roller coasters, but there’s other flavours.

Related: I dismiss the adult horror genre as entertainment based on the enjoyment(?) derived from watching people suffer/die by violence. I would like to read an article here on Tor that strives to convince me otherwise.

>24, thank you for that link, very interesting. I check at least some of those boxes, and know people who check more.

@Difficat. I ran a K-6 library for four years, and I miss it every day. Many middle-grade kids love scary stories, and Alvin Schwartz’s “Scary Stories to the Tell in the Dark” books were the gold standard. (Bonus points if they had the original Stephen Gammell art.) I had three copies of each one, and they were never on the shelves.

I think kids are smarter than we give them credit for generally. They may ask if werewolves are real at one point, but once understood, they understand what they are and aren’t in a story or on a screen. They may not understand that the X-Men are a metaphor narrative for adolescence, but they feel it. They feel that Wallace turning into a Were-Rabbit is about change, even if they don’t get the rest. They’re in a near daily state of change and flux. Our job I think as parents is to make sure they have a stable, reliable place to run to. Our job as storytellers is to remember that they need to have that safe locale waiting for them much earlier than we would in an adult narrative. There are clear cultural gestalt reasons behind why say, Zombies resonate so much these days. Our fears of the real world are deeply reflected by our pop-culture, and as such this kind of media provides a safe playground through which to process those fears.

For the record, most horror films are truly terrible. I’m not celebrating snuff, torture or slasher-porn like the Saw films, or Hostel, or whatever as a worthy recourse, but I do think films that spook in an intelligent way like The Conjuring, or Ringu, or The Innocents bring something far more important to the table. The enjoyment comes from the adrenaline rush these experience gives us. The manner is the trigger not the purpose in this. So not a big fan of murder violence myself either. But that’s just my subjective opinion.

Overall my my main point is that there are lessons and values to be found here if you wish to find them. If it’s not your thing, or you hate the experience, of course the value and benefit will evaporate. But if it’s something one is drawn to, or intrigued by, there are legitimate and healthy reasons for this, and there are tools to be learned.

love this debate and discussion though. All sides have brought up excellent points and done well to keep it civil. Well done everyone.

I’m a library assistant in the kids’ department of a major urban library system. Kids do seem to have a strong pull towards the more scary stuff, and this article did a good job of explaining why.

I don’t remember childhood being a picnic in the park myself, and I grew up in the more innocent 1960s-70s. At the time I remember wishing that someone would write stories that reflected certain realities more accurately.

Good essay, and – speaking as somebody who was reading stuff like Lovecraft and Stephen King’s “Salem’s Lot” by age ten – I agree with most of the author’s points. Unfortunately, “scaring the hell out of kids and making them like it” doesn’t seem to be an option in the bubble-wrap, safety-uber-alles culture that passes for modern American childhood.

If “culture” is the word for a system where grade schoolers are hauled out of class by the cops for nibbling their Pop-Tarts into a vague pistol shape; where high-school and even university-level coursework comes with “trigger warnings” because they might teach something interesting; and childish behavior is increasingly treated not as childishness, but as a mental disorder requiring medication and counseling. And any parent who lets their kids engage in unsupervised play runs the risk of being indicted for child neglect…or for child abuse, should they correct their child’s behavior with a swat on the bottom.

I’m glad I did my growing up in the late seventies/early eighties. Back then, you could be a kid without being arrested, medicated or expelled.

Unfortunately schools have become more concerned with avoiding litigation than teaching or letting kids be kids. There are some good reasons for this, but largely much of what made learning fun, or free or parents getting actual news when something happens gets shoplifted by lawyers. It’s something that has driven us all crazy here. The missing kid mil-carton pic is a good example of somethign that has made what is actually not an especially common problem seem like an everyday pandemic of threats, and I think it’s driven us all a bit crazy as a result. I hear teachers aren’t even allowed to touch children at all in many schools. Madness.

Another classic reference for the importance of leaving the scary bits in fairytales, etc. is Bruno Bettelheim’s “The Uses of Enchantent”. And as an aside (@@@@@ opnionated), I’m not sure how useful it is (in terms of arguement) to extract single sentences out of context from an author’s essay and then deconstruct them. Good points are surely brought up in your arguements, but they often stray from the authors intentions because the isolated sentences have been yanked out of their concpetual environment, and the subtelties and supporting ideas that he uses to back them up and clearly define them are no longer present.

I agree with the general premise of this essay. Reading is an important and safe way for parents to help their children develop empathy and the ability to deal with fear, conflict, peril… etc

Reading *together* is essential so you as a parent are there to guide them through sensitive and distressing topics. What better way to get to know your kids than by experiencing and discussing the stories we read and watch as a family.

My kids have very individual tastes in reading and movies, and thus they have very different reactions to horror elements. What is important IMO is that my dh and I are there with them to talk about difficult subjects, what they mean, how the characters dealt with them, how it could translate into real life, etc… We can very quickly tell when they are overly bothered by something, which gives us a heads up on what to avoid, or more often, in what areas they need additional help and guidance.

Also helpful – watching the special features on DVDs. It takes alot of the scary out of the dinosaur when you get to see his innards and the people who built them.

Just a small point, but surely Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm collected folk-tales. They did not write the stories, and they did not publish them with children in mind. Nor were the original stories intended specifically for children, but were told by adults to an audience that might well include children but was not exclusively childish. And some are most definitely not for children. How the Children Played at Butcher springs instantly to mind for example – in spite of the title.

@33

Thanks for making that point. The Grimm brothers were primarily folklorists. Subsequent editions of the stories they had collected were published for children and bowdlerised accordingly.

Really enjoyed the article, as a child who hated childhood (and still does! LOL) I loved horror because it took me to a higher plane, one that made me closer to adulthood.

My favourite person at that time (a relative 10 years older than me that I was incredibly close to) used to tell me horror stories and never shied away from telling me about the “real world” either, which I was and still am totally grateful for.

I didn’t cry at Bambi and got told off for mocking my friend about it, but I loved the part when the mother (?) is attacked by wolves on a ledge. I wanted more of that! I wanted a skeleton, I wanted mummies and Morlocks! And I truly got scarred for life watching the Wizard of Oz. That witch was horrific and gave me nightmares for years.

But in that fear was a sense of relief too that when the morning came , I was still alive! I would also get a sense of responsibility towards my fluffy toys, gathering them under the blanket, that safe haven that was my bed was my castle, and I would go to sleep my little head filled with monsters, very large wild animals and killers holding knives.

I recently was teaching a boy of 7 and we got into the habit of telling each other’s movies plot seen in the week. He completely got into my (softer)version of “cabin in the woods” and the mermaid details!

I agree that it is an important part of childhood and I also think that it is healthier than real violence as something to get fascinated by. Both can trigger similar emotions , excitement, fear, a sense of the forbidden, but as much as it is ok to get somewhat blase about horror movies/stories, it is not so about real violence. Kids know the difference between reality and fiction, deep down (i know I did), but blurring those lines from an early age can be dangerous. One should never get used to the hurt of others, real people or animals.

Meanwhile I think horror as a child was my porn! However, we must leave room to appreciate that some kids may not be into it.

I read your essay with a little bit a dread. I was one of those children who would cry at puppet shows in kindergarden, and my parrents had to get rid of my bed and buy a mattress when as an 8 years old I got my hands on a copy of Alien. I new with certanity that there were facehuggers under my bed!

What I find increadibly interresting in your argument, is that if I substitute sci-fi & fantasy in place of horror, I could not agree with you more! My safe place to experience dread and fear and adventures lay in a galaxy far, far away or at least in the distant future.

Anything that happened in my time or in familiar surroundings was just too real to me inspire anything but terror and sorrow in me.

For example in Hungary, Golding’s Lord of flies is on the mandatory reading list in elementary school. It scared me more than Alien ever could, precisely because I saw in my classmates the very real possiblity of becomeing like the children in the book.

So when I choose books for my nephews, the idea that they might enjoy horror never enterd my mind. Thank you for the idea, because I am despairing of finding for them THE book, the first one that captures their fancy so muchs that they will fall in love with reading itself forevermore. For me it was Kipling’s origingal The Jungle Book – scary, adventurous, but so far out of my reality as to be fantasy for all intents and purposes – and I couldn’t get them to sit through the first chapter.

They’ve already seen and been bored by the Disney version – that is something to protect your children form at all costs!

I think terms have to be more clearly defined before I can agree or disagree with this piece. I have seen the line between fantasy and horror as literary genres drawn both more leniently and more strictly than I would draw it (and the line separating them as marketing categories drawn just completely arbitrarily).

First and foremost: I scare easy, and I don’t consider being scared “fun” or “entertaining.” It pisses me off, really. (“Cabin in the Woods” for example, pissed me off for half a year. And I consider that ending to be a happy and positive one; I was that mad.) This is going to inform everything I say here.

I would never call “Bridge to Terebithia” horror, partly because nothing fantastic or speculative takes place in it. I would not automatically call “Coraline” horror at this stage in my life, because it doesn’t scare me, but child me would definitely have been afraid of it. However, child me was not at all afraid of fairy tales in which children’s heads got chopped off or evil queens had to dance in red-hot shoes, in part because of the matter-of-fact language with which these narratives were related. (Child-me WAS very afraid of Robert Louis Stevenson’s “Shadow March” — a short poem about a child going up the stairs to bed — because it contained the words “all the wicked shadows coming, tramp, tramp, tramp.” Child me was quite religious and seized very strongly onto the word “wicked.”) The narration, the focus, the atmospheric nature of this work is what stuck with me, what stuck *into* me.

As an adult I became very annoyed with the then-SciFi channel for showing horror films, which I did not consider valid fodder for the channel. When the main focus was not the science or the magic that went into the worldbuilding, but instead the plot — the same, repetitive kill-off-the-characters-one-by-one — became the main focus, I didn’t want to see the film. (“Alien” was the only exception to this, for me.) This was what my mind would leap to when I’d see people referencing horror. (And it’s not something I think children need — I don’t think exposure to that sort of horror helped me in the slightest as a child, whereas exposure to Stevenson I do think was edifying, and if “Coraline” had existed at that point, I wouldn’t begrudge my mother having read it to me.) (I’m less of a purist about the SyFy channel now, and more amused than annoyed at the inclusion of wrestling.)

Right now, I would still make a distinction between fantasy and horror, and between “difficult” or “dark” stories and straight-up “horror,” and the category of “horror” is something I would feel fine not exposing my child to, though I find myself edging more and more into it as I get even older — dipping my toes into it, even enjoying some. And I’m using another, different definition in this paragraph than I have been using, but it’s a difficult definition, one I’ve had a lot of conversations about over the past few years and months, trying to nail it down. I’ll try to clarify:

The problem for me with the stuff that most often gets classified as horror is that there is no hope in it. There’s hope in “Coraline.” There is hope in “Eutopia” by David Nickle (it helps in this story, as in “Alien,” that the antagonists are simply a species with differing reproductive needs, not sentient, unappeasable hell demons or similar). There is no hope that I acknowledge in your average zombie apocalypse narrative (seriously, how is the planet supposed to continue after that, just let the zombies have it), or your slasher-killer tale, or your “Ringu” where your evil thing simply lies in wait for the next victim. (Note also that in Japanese horror — which is why I say “Ringu” and not “The Ring” — as opposed to the Western version, the victims have a tendency to be truly innocent bystanders — they haven’t done anything to “awake” the ghosty evil, and it’s not mad at them specifically — and there is no way to appease it or to finish its unfinished business. It just is.)

Scares for the point of “proving that dragons can be beaten” as Gaiman quotes, I can see. Scares for the point of being terrified, I can’t. And if my kid comes upon such stories and likes them and seeks them out, that’s one thing — my parents let me loose in the library and did not censor my reading, and I agree with that tactic — but I wouldn’t ever pick them out for my kid in the same way I pick out warm clothing or healthy vegetables, because it’s “good for them,” because I don’t believe that. I don’t believe that being “deprived” of the hope-free stories is harm.

I suppose, in short, I’m saying 1.Genre is hard to define, 2. There is value in “difficult,” non-pat, non-trite stories of any genre, but also 3. I don’t think you have to go to the horror shelf for that, and I don’t think terrifying a child is an unequivocal virtue.

Excellent piece that immediately brought to mind watching the Harry Potter movie with the giant spiders with my niece (six or seven years old at the time). She helpfully told me a scary part was coming up, and clung to my arm as our heroes ran from the spiders. But she watched, because, in her words “it makes me feel brave to face scary things.” Kids need to feel brave, but we have to follow their lead when presenting the material.

I’d add Clive Barker’s The Thief of Always to the list. It exists at the intersection of fantasy and horror, and was written for kids as well as adults. It also ends on a hopeful note.

@37: I entirely agree with your point about hope. My girlfriend loves horror movies, so I’ve seen a lot more of them lately, and I’m getting tired of the bleak, hopeless endings. One in particular came out earlier this year and I enjoyed it right up until the pointless and unnecessarily hopeless ending. I was thinking that the presence or absence of hope is a good dividing line between dark fantasy and horror, but Alien has Ripley winning, yet is clearly science fictional horror. Best to think of genres as general guidelines, and not clearly delineated, precisely mathematical pigeonholes.

@37 – well said, I think you much more clearly communicated what I was feeling.

I think this has some parallels to some of the recent research on allergies: that kids today are having more allergies because they weren’t exposed to enough germs as infants and their immune systems never learned to distinguish harmless things like peanuts and strawberries from harmful bacteria. Let your babies play in the dirt! But don’t deliberately give them the flu.

As an American just discovering Doctor Who a few years ago (and loving it!), I was surprised to learn that in England this is a popular show for kids, and wished that I had found it as a child. When I wanted to watch a popular (very tame) animated movie with my little nieces, my sister recommended fast-forwarding through ‘scary’ scenes (anything remotely suspenseful or containing action) or pausing to explain that everything would be okay. I followed her wishes, of course, but I couldn’t help feeling like a little scare wouldn’t hurt them, and how could they really experience the story without that aspect of it?

I loved reading fairy tales and mythology as a child, but my favorite moments of “horror” were the stories my dad used to tell me. They were stories he made up was told by his father. There’s something powerful about the medium of oral scary-storytelling that many kids don’t get to experience, beyond telling the occasional ghost story at a sleepover, perhaps. I would recommend this experience to anyone. Scare your kids in a way that you can control (look at their faces and adjust the story as needed) and easily comfort them immediately afterward!

hum..sorry did not convinced me. in spite of some interesting ideas, overall i don’t think horror is good for people, depending on the amount of horror and the intensity of it it can do more or less harm on your spirit. horor can traumatise people expecialy children, bad dreams at night and creepy scary thoughts,

And yet, your screen name is Mary Shelly. Curious.

I love this article. As a child I was exposed to literature and movies that frightened the pants off me, but always in a fun and safe environment. These stories helped me understand what makes me afraid, how I naturally react to fear, and how to deal with it. They also taught me to recognize the difference between real danger and storybook danger. I’m thankful that I grew up in a household where ‘scary’ stuff wasn’t always tucked away from me. I had lots of fun romping with Nazgul and werewolves, and I learned so much about myself that I would never otherwise know.

I’m currently writing an academic paper on the effects that horror novels have on the way elementary school children perceive and handle fear. I just stumbled across this post while casually studying and you have completely validated me. I have always had a great love for horror that started when I was young, and I have been called crazy for it my entire life. But horror taught me how to be the person I am today. Coraline Jones taught me how to be brave. Goosebumps taught me to love the thrill. Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark taught me the joy of sharing stories with other people.

You hit the nail on the head here. Thank you for writing this.

As someone fairly recently escaped from childhood, I’d like to add my two cents. The one Goosebumps book kid-me tried to read gave me nightmares (it involved a girl realizing she was a ghost killed in a fire? Anyone know the title? I’d like to re-read it and see if adult-me is okay with it now) and I was never fond of violence, but many of the stories that “should” have bothered me never did, or they did in a way that both frightened and fascinated me. I loved that stories that twisted my understanding of reality so I saw things differently, and I didn’t distinguish much between genres. Still don’t.

My biggest problems with stories happened when someone either tried to make me read or watch something or tried to stop me from reading or watching something, however well-intentioned. Kid-me knew generally when something was too much. Though maybe I should have waited anther year or two to read Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde.

That said, I never thought I was all that interested in horror until I started making my own art and stories and started looking at what my imagination comes up with-often a mix of horror and fantasy, or horror and science fiction. The stories I liked never struck me as frightening, even when others said they were. I did sometimes get embarrassed when people looked at what I was reading and responded negatively, though.

Excellent column, well done, couldn’t agree more.

Cool beans, this really helped with a essay i had to do.

Thanks and goodnight

– Oldman Childnapper

Wonderful, I’d like to write a review in portuguese. Due credits and links to original included, of course.

Absolutely incredible! You have completely enlightened me and my children will benefit because of your post. Thank you!