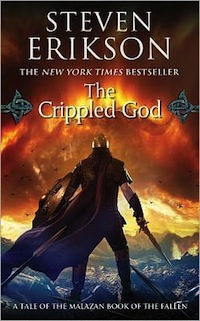

Welcome to the Malazan Reread of the Fallen! Every post will start off with a summary of events, followed by reaction and commentary by your hosts Bill and Amanda (with Amanda, new to the series, going first), and finally comments from Tor.com readers. In this article, we’ll cover chapter ten of The Crippled God.

A fair warning before we get started: We’ll be discussing both novel and whole-series themes, narrative arcs that run across the entire series, and foreshadowing. Note: The summary of events will be free of major spoilers and we’re going to try keeping the reader comments the same. A spoiler thread has been set up for outright Malazan spoiler discussion.

CHAPTER SUMMARY

SCENE ONE

Aranict, looking at the Glass Desert, its splintered bones, thinks, “It felt like a deliberate act, an exercise in unbelievable malice… Who could have done this? Why? What terrible conflict led to this?… If despair has a ritual, it was spoken here.” The Lether army is hastening to catch up to its allies, after Brys had lingered to the last moment with Tavore. As he’d watched the Malazans march away, Aranict was shocked to see what looked like despair in his eyes. She recalls how the Malazans had saluted the Letheri. She cannot get that image out of her head: “Who army are they? These Bonehunters. What is their cause. And the strength within them, where does it come from?” She thinks Tavore is not the source, but merely the focus. “I saw in their faces the erosion of her will, and they bore it. They bore it as they did all else. These Malazans, they shame the gods themselves.”

SCENE TWO

Brys eyes the Letheri Imperial Standard, “a fair copy of Tehol’s blanket,” with an image of Tehol’s bed and under it, six plucked (but living) hens. He smiles, much to Aranict’s pleasure (she’s been worried about his mood, how he’s closed himself off to her). They discuss Tavore, with Aranict telling him the Adjunct has given him nothing and that he should not be like her. He thinks of the Guardian, of how he now knows “the names of a thousand lost gods.” He wonders if the name will stir the god’s soul, if he will “Force its eyes to open once more? To see what lies all about us, to see the devastation we have wrought.” He now understands, he believes, Tavore’s silence: “Must the fallen be made to see what they died for, to see their sacrifice so squandered? Is that what you mean… by ‘unwitnessed.’” He tells Aranict he thinks he has figured out that Tavore “gives us silence because she dare not give us anything else. What we see as cold and indifferent is in fact the deepest compassion imaginable.” They meet Stormy, Gesler, Kalyth, Grub, and Sinn (the two children, especially Sinn, scaring the hell out of them). Gesler tries to relinquish command, he and Stormy fight. Stormy implies Gesler was Mortal Sword to Fener (Gesler says he doesn’t know if he was or not) and Gesler says Stormy betrayed the Empire (Stormy says he did what Cartheron and Urko asked him to do). Gesler leaves still in command.

SCENE THREE

Riding away, Aranict tells Brys Gesler and Stormy are almost at godhood-level and are hanging on with all they can to keep their humanity. Everyone thinks Sinn is scary, and Aranict says Tavore sent Sinn with Gesler and Stormy because nobody else can stand against her, her fire. She calls Grub Sinn’s “conscience made manifest,” and says if it comes down to “who we can save… it must be the boy.” Brys tells her what happened to him when he died and his suspicion that “I was released to do something. Here, in this world. I think I now know what that thing is. I don’t know, however, what will be achieved. I don’t know why it is so important.” He says he has had visions of someone “bearing a lantern… A moment of light. Relief From the terrible pressures, the burdens, the darkness… Does he wait for the souls of the drowned? It seems he must.” He tells her he has a voice inside him of “all that the seas have taken—the gods, and mortals—all the, the unwitnessed. I am as bound as the Adjunct.” When she asks, fearfully, if she will lose him, he thinks, “I don’t know.”

SCENE FOUR

Krughava and Tanakalian argue. He tells her as Tavore is a mere mortal, she had no right to avow the Perish to her, the Perish who are “Children of the Wolves.” He points out they are now in the position of having to betray someone:

Upon the side of the Adjunct we are offered a place among mortals… Upon the other side, our covenant of faith…In this faith we choose to stand alongside the beasts. We avow our swords in the name of their freedom, their right to live, to share this and every other world… Are we to be human, or are we to be humanity’s slayers?… Should we somehow lead a rebellion of the wilds, and so destroy every last human… Must we then fall upon our own swords?… In choosing one side, we cannot but betray the other.

He distinguishes the Perish from other cults of war because they do not seek glory, or the defeat of enemies, but war, “For it is not our glory that we seek… It never was.” He says as well that once they win, they will not need to kill themselves (as humans), because there will always be a need for them, because there is no such thing as a “final war” as Krughava says. He wins the listeners, and Krughava surrenders her title as Mortal Sword, and when Tanakalian begins to talk of what might happen should she “rediscover” her faith, she turns it on him to talk of if he discovers his “humanity.”

SCENE FIVE

Krughava meets with Abrastal and Spax and tells them of what happened. They discuss Tavore, and Krughava reveals that her vow to the Adjunct came from her seneschals’’ visions of Tavore, “a mortal woman, immune to all magics, immune to the seduction of the Fallen God’s eternal suffering [holding] something in her hand [that] had the power to free the Fallen God. It had the power to defy the gods of war—and every other god. It was a power to crush the life from vengeance, from retribution, from righteous punishment. The power to burn away the seduction of suffering itself.” She thinks what she saw in Tavore had been a lie, what she [Krughava] had wanted to see, and that Tavore is desperate and uncertain, she “stumbles.” She thinks Tavore looked to her as a source of strength, and now she has turned Krughava away, has “lost her faith,” is filled with “despair.” Through all this she hasn’t identified what Tavore held, and when Abrastal keeps asking, Spax finally answers: “its name is compassion. This is what she holds for the Fallen God. What she holds for us all.” Krughava declares, “It is not enough.”

Amanda’s Reaction

It might be time again to mention that this series demands proper reading, as in, wondering why each word has been chosen. Here in the first paragraph of chapter ten, Erikson has Aranict view this ominous desert as akin to a shoreline. With the Shake and the Shore, are might see shoreline as a specifically chosen word here. Of course, it might be complete coincidence, but this is why attention must be paid.

God, what on earth happened in this desert to make Aranict—who has shown herself to be pretty sensitive—on the very verge of vomiting all the time. “This place, it wants to kill me.” I think I’ll be striking this desert off my bucket list of holiday destinations!

And this vision that Aranict had of the Bonehunters as they marched into the desert and towards what everyone thinks is their inevitable destruction is just breathtaking in its sorrow and despair:

“Those faces. Horrifying in their emptiness. Those soldiers: veterans of something far beyond battles, far beyond shields locked and swords bared, beyond even the screams of dying comrades and the desolation of loss.”

It is especially poignant when you consider how we’ve spent some time with the Bonehunters, watching as they have come to terms with their dead and closed ranks.

And how will the gods react to being shamed thusly by the Bonehunters: “These Malazans, they shame the gods themselves.” I suspect some gods wouldn’t take at all kindly to that assessment.

Ha! I love the idea of that standard, with the image of Tehol’s rooftop bed and those damnable chickens on it. And the conversation between Tehol and Brys is gigglesome—“Oh, that’s all I ever hear from you, brother! ‘It’s not that way in the military, Tehol’, ‘The enlisted won’t go for that, Tehol’, ‘They don’t like pink, Tehol’.”

I’m not quite sure how important Brys’ musings are on both the fact that he doesn’t really like Tavore, and the fact that he holds the names of a thousand lost gods. The latter strikes me as something that will probably end up being vital, particularly with seeing various lost and forgotten gods through the first part of this novel.

Eep. Aranict is clearly desperately shaken by her first view of Sinn and Grub.

And here this discussion of who will take overall command, where Brys is quite happy to cede power to Gesler and Stormy—he certainly seems to understand that these two marines are way more than what they seem to be. And then Gesler—a reminder that he was once of Fener. A timely reminder, I think, considering we know that gods are stirring all over the place, and the jade statues are falling, and Heboric has been found and retrieved.

Oh damn. Now this made me shiver:

“Because,” he whispered like a man condemned, “she trusts us.”

I guess being conferred the trust of Tavore means that, by God, you will not break that trust.

And wow. The conversation between Aranict and Brys about the closeness of Gesler and Stormy to ascending, and their time in the Hold of Fire, and the fact that they are there to survive Sinn’s power of fire when she tries to set the world alight. That is a LOT to take in all at once. And these words about Grub from the Adjunct: “She said he was the hope of us all, and that in the end his power would—could—prove our salvation.” What role is it that Grub has to play?

I’m uncertain about the meaning behind the rest of their conversation, where Brys confesses some of his thoughts and memories concerning his death and resurrection. He is here for something—and perhaps it is related to Grub? More than that, I am not certain about.

Ah, I did wonder how the Wolves being part of the Forkrul Assail alliance would then impact on the Perish. And here we have Tanakalian arguing for his gods and therefore against the Adjunct. I have to say, much as I don’t like him and all, he argues a valid point for his people and for his religion, something that Krughava doesn’t seem to have contemplated when she vowed to stand with the Bonehunters.

Having said that, he is of course arguing for the destruction of all humanity so that the Wolves can take their place again, so I am glad to see Krughava step down as Mortal Sword of a force that she is no longer avowed to. But, damn, this is a real weakening for the Bonehunters. This really is the betrayal of the Adjunct by the Perish.

I totally agree with Krughava when she shouts that the Wolves of War are a “damn cult”. Which makes Tanakalian a zealot, and they can be some of the most dangerous people.

I think that the children of the Snake are going to give Tavore and her Bonehunters back their compassion, they’re going to take away some of their despair and leave them with faith again. I hope so anyway. Because Krughava’s picture of the Adjunct losing faith and leaving compassion behind is not one that I even want to contemplate.

Bill’s Reaction

This is not the first time we’ve had intimations of something horrible having happened in this desert. The question now becomes, will we ever learn what that might have been, or will this be one of the many hint-of-something-in-the-past-but-never-explained-that-enriches-the-worldbuilding kind of things.

If Aranict is right in her senses, it was something of “malice” and of “despair.” That later a concept that runs throughout this chapter and that we’ve seen earlier and, one might guess, will continue to see. It comes up with Tavore, it comes up with Brys, it comes up with the Malazan Army, it comes up with the Snake, it comes up with Twilight. Some people we see defy despair, others seem to fall to it (Blistig?) and others we don’t quite yet know how they will face it. This all reminds me too of another work that looked quite a bit at despair and in fact, if memory serves (I’m not sure if it does) might have invoked a “Ritual of Despair”—the Chronicles of Thomas Covenant.

A powerful image, and another of those ones you’d love to see on-screen—that moment when the Bonehunters pass by and salute the Letherii. So many lines in here, especially lately, that just whisper a thrill across my neck with regard to the Malazans: This “They bore it as they did all else. These Malazans, they shame the gods themselves.” Is another such.

Love that standard. And the switch from despair to not just humor, but someone who is impossible to picture succumbing to despair—Tehol. While I think he has generally shown good balance, it seems to me (and this may just be because we’re near the end and there is so much darkness) that Erikson has been particularly deft lately in balancing the grim and the light, of moving us smoothly and at just the right moments between the two moods.

On the other hand, the dialog about riding across the old lake bed and the “ground underneath us is uncertain” is one of those too on-the-nose lines I’ve pointed to here and there.

We’ve had several intimations of Brys being back as part of a kind of “destiny” and also some intimations that he might not survive that destiny. This dialog strengthens both feelings, explicitly so for each.

I like how that summoning of a god via their name is given a bit of a twist here in that such a summons is not (necessarily) a summons of “power,” nor is it (necessarily) a positive. But here it is couched as a potential curse, a horrible thing to do—to bring a god back and make it see what the world has become in their absence. And I like too how Brys connects this in his mind to Tavore’s use of “unwitnessed”.

More and more we are given a sense of Tavore’s aloofness and coldness being merely a cover of the exact opposite. We saw it not too long ago with the burden she carries sussed out when she was healed and now we have Brys, using non-magical means, coming to much the same conclusion. And of course, his speculation that her silence is in fact great compassion not only obviously fits smoothly within the steady drumbeat of that theme since book one, but also sets us up for the end of this chapter.

Well, if anyone isn’t expecting by now that at some point before the end of the book Sinn is going to go bats—t crazy and try and burn the universe down, I’m not sure they’re reading the same book I am…

While Stormy and Gesler add some comic relief here, I’ll also point out that the question as to whether or not Gesler was a Mortal Sword of Fener’s is something that we should probably pay attention to, as we know Fener has a part to play in all this.

Just as we should pay attention to the fact that the two of them are on the verge of ascending (something we’ve been told before about them)—they might just need to be at the high level for what is coming. Or for Sinn, as is strongly implied. Just as important as their closeness to being gods is why they are not yet there—they are actively resisting. They are hanging on by their fingernails to their “humanity”—and if one reads that as not simply “being human” but humanity in the sense of “empathy” or “compassion”—the refusal to get too high, too aloof, to feel, then this obviously plays into The theme of the series. I also like how this comes so soon after we had the scene with Cotillion, who is also fighting to hold on to, or remember, that same humanity. This reading of “humanity” is not only implied by the word’s connotation, but become explicitly connected by Aranict calling their example of humanity “Like a ritual. Of caring. Love, even.”

Well, we’ve been set up for this conflict in the Perish for some time now. I like how clearly and explicitly Tanakalian makes his arguments—it’s all laid out very simply, very clearly, very logically. It all makes perfect sense. And it’s also clear, if one follows his logic, that this would put the Perish not just on the side of the “wild” or the Wolves, but based on alliances (whether overtly so or just matters of converging goals), it would also put the Perish on the side of the Forkrul Assail, several of whom have phrased their own justifications in much the same way—this defense of the animals against the destruction of humans (“I speak for the trees!”). And of course, this would also connect them pretty darn strongly to Setoc, who perhaps not coincidentally we left muttering about thousands of “iron swords.”

Also on this topic, when Tanakalian mocks the idea of a final war, are we meant to nod our heads at his pragmatic insight (“Ahh yes, World War I, the “war to end all wars”) or sorrow at the inability of humans to even countenance the possibility of a last war?

And when he says “Hood take the Fallen God”, are we to recoil at the clear lack of empathy, of compassion, or consider if his marshaling of the wild’s defense might be a compassionate act? (I have my own ideas.)

When we see Krughava later in her conversation with Abrastal and Spax, it seems to me that her reading of Tavore is more characterization of Krughava than of Tavore, as is her judgment on whether compassion will be enough. Even so, her description of the power of compassion is one of the most blunt expositions of the theme that runs throughout the series—it’s all laid out right there.

Amanda Rutter is the editor of Strange Chemistry books, sister imprint to Angry Robot.

Bill Capossere writes short stories and essays, plays ultimate frisbee, teaches as an adjunct English instructor at several local colleges, and writes SF/F reviews for fantasyliterature.com.

I’ll comment more later, I just wanted to express some love for how Tehol can completely steal a scene despite not actually being physically present.

I’ve always had a soft spot for Bruthen Trana (the Edur who resurrected Brys), and I always found this a deeply sad image of his current ‘fate’, as Brys sees him wandering the depths with his lantern. Is there more to this brief mention of Bruthen here? What are we being set up for?

Another image from this chapter which is etched in my mind is that of Krughava explaining the vision of Tavore to Abrastal and Spax, recreating it by holding her empty hand out as we’re made to think about what it is that is held there. I think this is the most ‘human’ that we’ve seen Krughava.

Relatedly, this chapter is exactly why I think SE’s done such a masterful job with the character of Tanakalian. We all KNOW that he’s a prat, and unlikeable, and choosing the wrong side by dismissing the Adjunct, but at the very same time it’s so damnably hard to pick holes in his logic! Again he ‘seems’ to be the one making sense, in terms of what the Perish are ‘supposed’ to be about.

And this too is an excellent upending of expectations. Here we see that it is Krughava, who has previously been pictured (via Tanakalian) as an arrogant brute, the physical manifestation of all that is wrong with a warrior cult, who is actually the one seeking reform and modernisation of the order, to something that makes far more realistic sense. While on the other hand it is actually Tanakalian, despite all his talk about being a different type of Shield Anvil, who is setting the Perish down the logical conclusion, without deviation, to the stated beliefs of the Order’s foundation.

We’ve had the discussion about Mortal Swords/ Destriants/ Shield Anvils before.

However, I find it interesting that Gesler says he was never sure he was really Fener’s Mortal Sword. This is related to the exact moment when Brukhalian of the Grey Swords became Mortal Sword to Fener.

@2

It’s an argument of warrants, IMO. At the root, the only way to buy Tanakalian’s argument is to accept the premise he’s arguing from. If you accept his premise, then yes, he argues very well. But he’s also assuming that his premise is the truth of the Perish, and Krughava does not accept that premise. But rather than weaken the Perish at the idealistic level, she chooses to walk away rather than fight. That’s pretty much what has to happen when warrants clash.

How much different would this book turn out if Krughava had said no, you’re wrong, and lopped off Tanakalian’s head right then and there…

Yes I agree that we’ve been well set up for this betrayal of the Perish, especially when the Forkrul Assail mentioned the Beast-Gods as their allies. And reading Setoc’s passages it should have been clearer a lot earlier.

But how does Toc fit in? And how could the Perish even have a destriant, when Setoc is the real one?

(I apologize if this was discussed in an earlier chapter, I haven’t been as closely following lately as the series deserves. I will catch up though).

@travyl

Setoc became Destriant upon Run’Thurvian’s death. Prior to that, she was just a relatively feral child, hiding in the wilderness.

Tanakalian is fascinating here – he speaks with authority, with conviction, and at the same time by casting down his rival, he claims the authority he feels he deserves – leadership and glory, and Power.

And I so cannot wait until he comes face to face with Setoc.

Gesler and Stormy are the epitome of the Malazans – black humored, loyal to the end, and the sort to spit in the eye of whatever god would claim them. And yet you see the softer side, and the friendship, and the clinging on to what they see as important.

And the last comment on Tehol – his banner –

At this distance, the standard looked like a white flag

Can you think of a more appropriate military banner?

Indeed there’s a lot of ways to interpret this. I kind of feel like it’s a bit of “humans show compassion to the CG when he’s a problem for them, but where was that compassion for the wolves and beasts when you cleared our forests, hunted us all down and made so many of us extinct?”

——-

re: Mortal Swords/Destriants/Shield Anvils – we have indeed talked about it before, and one thing that is worth pointing out again here is that these titles can and are used by people without being the “real” thing. In Fener’s priesthood on Genebackis, the title of Destriant was used as a rank in the priesthood itself – ie Rath’Fener said his rank was Destriant. There were probably a dozen or more Destriants across the church of Fener, and have been for quite some time, but none of them were probably really the chosen ones of Fener – that was Ipshank and then Karnadas. Same with Mortal Sword.

So in the same tradition as the Grey Swords (and probably any other Elingarth/Perish-style mercenary companies), the leaders of the Grey Helm are titled as the Mortal Sword, Destriant and Shield Anvil. For all we know, Krughava might not even be the chosen Mortal Sword of Togg/Fanderay. Run’Thurvian *seemed* like the real deal, but even then a powerful and devout priest who isn’t the official Destriant can probably still journey to their gods’ feet, anyways.

Finally, there’s no reason a god or goddess can’t have more than one Mortal Sword, as long as they are willing to use their own power to support both (or more) servants. Maybe it waters them down a bit, but so what? Hood had multiple Soldiers, and swapped around his Soldiers and Knights, too. God and goddesses can have other powerful servants that aren’t specifically a MS/D/SA, too (there’s a good example of one of those coming up, too).

I would say Setoc is most definitely a chosen servant of the Wolves – she clearly has been given powers and guidance beyond mortal capabilities and of a nature that matches the Wolves. Until they demonstate otherwise, we can’t know for sure if Krughava or Tanakalian are truly chosen servants of the Wolves or not. They certainly *aspire* to be, but as far as we know that hasn’t been completely confirmed. It was probably a similar case with Gesler – he aspired to be Fener’s Mortal Sword, but even he doesn’t know if he truly was or wasn’t at the time.

the revelation about Gesler swearing his men to Fener was a good one, but i like the afterthought reveal that Stormy had something to do with urko and cartherons disappearances, or at least lied to surly about their defection.

i also love aranict in this chapter, as she is so astute and intuitive about stormy and ges, as well as the wunderkids and the desert. really coming out of her shell here coming into her potential as Brys’ equal.