Full disclosure: I was expecting the film adaptation of The Giver to be garbage. Though I was thrilled at the prospect of Jeff Bridges in the nominal lead, the second they cast a 24-year-old Hayden Christensen-alike as Jonas I promptly and irrevocably abandoned all hope (Jonas is twelve, guys. He’s twelve!). I won’t say I was pleased that, in the end, it wasn’t garbage. It was more of a sand-rash of a movie, if you will—irritating but it isn’t exactly going to ruin your day, and hey, at least you got out of the house.

But one thing that did live up to my expectations was that the changes made to the material to make it more marketable as a movie would be changes for the worse. The filmmakers took this quiet, contemplative coming-of-age story and reshaped it for a market it simply wasn’t designed for.

The Giver wasn’t written in the midst of the current YA deluge; hell, nowadays it isn’t even considered YA, occupying the shorter, less kissing-driven “middle grade” demographic. Being marketed to a younger audience than Twilight and its contemporaries, it is also something of a controversial book for introducing difficult and complex sci-fi concepts to a young audience that (arguably) has not yet been exposed to such things. The depiction of euthanasia, for instance, and euthanasia of newborn babies no less, was always going to be a hard sell if you are really and truly trying to make a movie for children.

The Giver is not a movie for children. It is a movie for teens, young adults and people with a high threshold for boring. It isn’t even the most recent new release to come out under the increasingly dubious label of “YA adaptation” – that honor goes to The Fault in our Stars coattail-rider If I Stay, which came out last week, putting us roughly at half a dozen YA adaptations for the year so far.

Most of these lower-budget attempts—and I say “lower-budget” relatively speaking—have the same aspirations as their forebears in mind: the possibility of a big franchise with brand-name recognition with relatively low investment at the front. Up until this year, with the success of Divergent and The Fault in Our Stars, most of the non-Twilight/Hunger Games YA adaptations that have come out in the last three years have been disappointments critically and, more importantly, financially.

The strange thing about most of the YA adaptations, successful or no, is that they’re not the product of major studios—they’re the product of indies and mini-majors like Lionsgate or, in this case, The Weinstein Company and Walden Media. Part of the reason for this is the lower upfront investment than you see in other modern brand name franchises, your Transformers-es and Ninja Turtles-es and the like—YA adaptations represent greater risk, and greater reward, but what we’re seeing now is an increasingly narrow window of what they are even allowed to be.

Up until Divergent, the industry was peppered with flaccid attempts to ape the success of Twilight and The Hunger Games, the intent for almost all of them to create a successful franchise. 2013 alone gave us such non-starters as The Host, Beautiful Creatures, Ender’s Game, and The Mortal Instruments: City of Bones. But none of these potential franchises were quite so overt as The Giver in trying to fit into the very specific trend of YA dystopia. And in trying to ape the success of franchises like The Hunger Games, the film misses what made the source material appealing in the first place, thereby creating a final product appealing to no one. Divergent didn’t need to change much from its source material in order to appeal to fans of The Hunger Games. The Giver, unfortunately, did. It wasn’t the worst of this stolid group of underperformers, but it might be the worst case of “taking something and morphing it into what it’s not.”

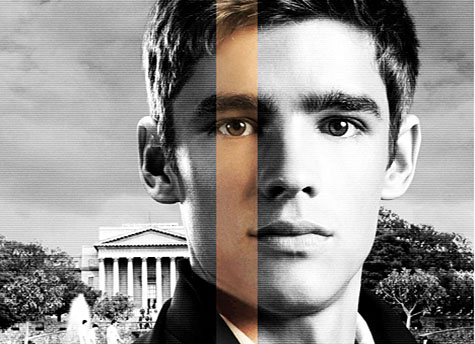

A side effect of the YA adaptation boom is the near-extinction of live action movies with child protagonists. The Giver was a quiet, contemplative book for adolescents that in a perfect world would have translated into a quiet, contemplative movie starring adolescents. The story of The Giver was tailored for younger characters, creating a strange and awkward story when the characters are aged up to a demographic with a wider market appeal. This entire cast is way too old for this story. Particularly Brenton Thwaites, the actor who plays Jonas. He’s got age lines. He’s getting mail from AARP. He is old.

The film also added a few action elements to bring it closer to its more successful dystopian contemporaries, namely with the character of Asher, who in the film has been upgraded to drone pilot. I saw many fans of the book planning to steer clear of the film specifically because of the addition of the action elements; to such book fans, I can tell you that it’s exactly as pointless and contrived as you assumed it to be. The “Asher the drone pilot” subplot is built up lazily, adds no real tension to the story, and has a terrible, anti-climactic payoff. As with the aging up of the child characters, the addition of minor action elements serves only the widening of potential market appeal and works to the detriment of the story overall.

I want to be clear that adaptation is not the enemy—it can be a good thing. I was genuinely impressed to the changes made to Catching Fire, almost all of them to the film’s benefit. The changes to Catching Fire were changes that benefitted the story, not to make it fit in with a market. The Hunger Games franchise has that luxury; smaller, older books like The Giver, less so.

In this regard, perhaps the closest point of comparison to the movie version of The Giver is the movie version of The Mortal Instruments: City of Bones. Unlike some, I don’t consider the Mortal Instruments books to be The Worst Ever. They’re no Hunger Games, they are by no means a literary treasure, but they’re perfectly serviceable urban fantasy that are snappy and easy reads (especially if you’re into maybe-incest). The movie was faithful to the book in terms of most of its plot elements; what was off was the tone, and what that tone was trying to emulate was Twilight. The result was strangely dour, deadly serious, and completely at odds with the tongue-in-cheek source material.

The film version of The Giver might have retained its adolescent protagonists, contemplative tone and mostly internal tension had it been made in the ‘80s or ‘90s. One could imagine something in the aesthetic vein of E.T. or The Neverending Story. But the market has little room for films of that type anymore, so why Walden Media and The Weinstein Company chose The Giver as their attempt to hop on the YA adaptation gravy train is somewhat bewildering.

As a coming of age story, The Giver has to hit you at just the right time in your development. It introduces all measure of storytelling mechanics and, for those who read it at the right time, becomes one of the first books you read that expects you to fill in the blanks and extrapolate for yourself rather than holding your hand through whatever message it’s trying to teach you. In theory, the same would apply to the film version (and might have come close were it not for one of the most God-awful voice overs in recent memory). There’s something deeply special about the bond between Jonas and The Giver, an adolescent beginning to understand the pain and complexity of life empathetically guided by a worn yet caring father figure.

Aging the characters up, jamming in a romance, peppering it with extraneous action scenes and casting the film with JC Penney catalogue actors does more than rob the film of that special bond. In the end, all we got from it is yet another failed carbon copy YA franchise.

Lindsay hosts the web series “Nostalgia Chick” and “Booze Your Own Adventure” and is co-founder of ChezApocalypse.com. If you want your timeline flooded with tweets about cartoons from the 90s and Michael Bay, you can follow her on Twitter.