So, what do you expect to see when you watch an Exodus movie? (1) A Pillar of Fire, (2) A Burning Bush that Talks and is Also God, (3) the Parting of the Red Sea, (4) pre-Freudian rods that turn into pre-Freudian snakes, and (5) at least a couple plagues. This version of Exodus has some of those things, but not all—we’ll get into what it leaves out in a minute. But it also adds a few things that are just fascinating.

Spoilers ahead for the film, but also…it’s Exodus…

Let me preface this review by saying that the day after I watched Exodus, a colleague asked me a difficult question: Is the movie better or worse than the state of contemporary America? I’d have to say…better? But not by much. Two weeks ago I ended up writing a recap of the TV show Sleepy Hollow while the Michael Brown decision came though, and since that show deals explicitly with the racial history of the US, I tried to write about my reaction within that context. Two weeks later I attended a screening of Exodus near Times Square, a few hours after the Eric Garner decision, and when I came out people were marching through the Square and over to the Christmas tree in Rockefeller Center.

I joined them, and it was impossible not to think about the film in this context as I walked. Ridley Scott’s film, which attempts a serious look at a Biblical story of bondage and freedom-fighting, undercuts its own message, tweaks the Hebrew Bible in some fascinating (and upsetting) ways, and comes off as incredibly tone deaf by the end.

So let’s get this out of the way: yes, Exodus is pretty racist. But it’s not nearly as racist as it could have been. Or, rather, it’s racist in a way that might not be so obvious right away. But at the same time—wait, how about this. Let me get some of the film’s other problems out of the way first, and I can delve into the racial aspect in more detail further below.

Can you tell I have a lot of conflicting feelings here?

As much as I’ve been able to work out a overarching theory behind this movie, I think Ridley Scott wanted to one-up the old school Biblical spectacles of the 1950s, while also folding in some of the grit and cultural accuracy of Martin Scorcese’s Last Temptation of Christ and (very, very arguably) Mel Gibson’s The Passion of the Christ. This is an interesting idea, and could have resulted in a moving film, but since he doesn’t fully commit to any one thing, the film sort of turns into a weird stew. He checks off the Biblical Epic box by showing the film in 3D. Which, um… have you ever wanted to sit in a movie theater while flies zing past your head? Have you ever wanted to watch the action in a film unfold six yards away, while you crouch behind bushes? Have you ever wanted to look a CGI locust right in the eye? Cause that’s pretty much what the 3D is for here.

Meanwhile, for Grit and Accuracy, the Plagues get (ludicrous) scientific explanations. The battles, starvation, and boils are all depicted as horrific, and Rameses is a terrible despot who tortures and executes people with no concern for public outcry. In a move that also flows into the film’s greatest flaw, all of Moses’ interactions with God are framed as possible delusions. His first interaction with the Burning Bush happens after he falls and whacks his head. His wife tells him it was just a dream, and Moses himself explicitly says he was delusional. The film also gives us several scenes from Aaron’s point of view, in which Moses seems to be talking to empty space. The interpretation rings false. Why make weird gestures towards a critical perspective on the Exodus story but then cast your Egyptian and Jewish characters with white actors?

In Last Temptation of Christ, Martin Scorsese plays with the conventions of old Biblical spectacles and the class differences between Jews and Romans in a very simple way: the Romans are all Brits who speak with the crisp precision of Imperial officers, and the Jews are all American Method actors. This encodes their separation, while reminding us of the clashes between Yul Brynner and Charlton Heston, say, or the soulful Max Von Sydow and the polished Claude Rains in The Greatest Story Ever Told. In Exodus, it can only be assumed that Ridley Scott told everyone to pick an accent they liked and run with it. Moses is… well, there’s no other way to say this: he sounds like Sad Batman. Joel Edgerton seems to be channeling Joaquin Phoenix’s Commodus with Rameses, and uses a weird hybrid accent where some words sound British and some are vaguely Middle Eastern. (Actually, sometimes he sounds like Vin Diesel…) Bithia, Moses’ adopted mom and daughter of the Egyptian Pharaoh, speaks in what I’m assuming is the actress’ native Nazarene accent, but her mother (Sigourney Weaver) speaks in a British-ish accent. And Miriam, Moses’ sister, has a different vaguely British accent. Ben Kingsley sounds a bit like he did playing the fake-Mandarin. God speaks in an infuriating British whine. Where are we? Who raised whom? Why don’t any of these people sound the same when half of them live in the same house?

We also get the De Riguer Vague Worldmusic Soundtrack which has been the bane of religious movies since Last Temptation of Christ. (For the record, LTOC is one of my favorite movies, and Peter Gabriel’s score is fantastic. But I’ve begun to retroactively hate it, because now every religious movie throws some vaguely Arabic chanting on the soundtrack, and calls it a day.) Plus, there are at least a dozen scenes where a person of authority orders people out of a room, either by saying “Go!” or simply waving their hand at the door. While I’m assuming this was supposed to be some sort of thematic undergirding for the moment when Pharaoh finally, um, lets the Hebrews go, it ended up coming off more as an homage to Jesus Christ Superstar. And speaking of JCS…. we get Ben Mendelsohn as Hegep, Viceroy of Pithom, the campiest Biblical baddie this side of Herod. That’s a whole lot of homage-ing to pack into a film that’s also trying to be EPIC and SERIOUS.

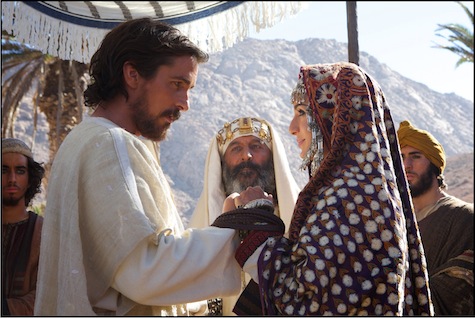

When Dreamworks made Prince of Egypt in 1998, they worked to keep the story as Biblically accurate as they could, while also deepening the relationship between Rameses and Moses for added emotional resonance, and giving Miriam and Moses’ wife, Zipporah, larger roles. Exodus does this, a little bit, but in ways that don’t completely work. When the film opens, it seems like Rameses and Moses have been raised together as brothers, with Seti giving them each a sword engraved with the other’s name to remind them of their bond. Only Rameses can inherit the throne, and Moses doesn’t want it, but there is still constant tension between them. Unfortunately, the film doesn’t really establish that they see each other as brothers as much as it shows you that they don’t trust each other, and Rameses does in fact kick Moses to the curb at the first possible opportunity. Miriam’s role is tiny (she does come across as much more tough-minded than her brother) and then she disappears from the rest of the film. The marriage ceremony between Moses and Zipporah (the film has changed her name to Sephora, but screw that, I like Zs) is actually kind of sweet. They add some interesting… personal… vows, which caused some laughter during my screening. María Valverde plays well as fiery wife-of-Moses, and their relationship is a good equal partnership, until God messes it up.

The depiction of the Ten Plagues is unequivocally great. Each new horror is worse than the last, and unlike any other depiction of this story (even the awesome Prince of Egypt) you really get a sense of the reality of the plagues. When the fish die, we see the flies and maggots billowing all over the land. The flies themselves are everywhere, and we see a man screaming as they swarm over his eyes, nose and mouth. When an ox dies suddenly, we see the owner, who was moments before yelling at the animal to behave, weeping and holding its head. We see herders on their knees surrounded by their fallen flocks, and we see people starving as their crops fail. It drives home the fact that these people are absolutely dependent on their livestock and the land that sustains them. The film also does a great job moving between the classes, showing us the plagues from the perspectives of farmers, doctors, poor mothers, wealthier mothers, basically everyone they can fit in, before checking in with Rameses and Nefertari in the palace. And the death of the firstborn children is as chilling as it should be.

The other throughline seems to be a half-hearted exploration of Moses’ skepticism. And this is where the film really fails. There’s no other way to put this. If I was God, I would sue for defamation over this movie.

Allow me to elaborate.

You know how in Erik the Viking the Vikings finally get to Valhalla and they’re all excited (except the Christian missionary, who can’t see anything because he doesn’t believe in the Norse gods) to finally meet their deities, and then they discover that the Norse pantheon is a bunch of petulant children, murdering and maiming out of sheer childish boredom? That’s the tack this movie takes. Which, in Erik the Viking, worked great! Just like the creepy child/angel who turns out to be an emissary of Satan was perfect for The Last Temptation of Christ. But for this story? You need a God who is both utterly terrifying, and also awe-inspiring. You need the deity who is capable of murdering thousands of children, and the one who personally leads the Hebrews through the desert. You need that Pillar of Fire action.

So let’s begin with the fact that God is portrayed as a bratty British child. Rather than a disembodied voice issuing forth from the burning bush, this child stands near the bush and whines at Moses about forsaking his people and orders him to go back to Memphis. You don’t get a sense that this is a divine mystery occurring, just that Moses is truly, desperately afraid of this kid. The child turns up in a few following scenes that are more reminiscent of a horror movie than anything else, which could work—getting a direct command from the Almighty would be about the most terrifying thing that could happen to a person—but since the child comes off as petulant rather than awe-inspiring, none of Moses’ decisions make any emotional sense. This man, who has been a vocal skeptic about both the Egyptian religion and that of the Hebrews, has to make us believe in a conversion experience profound enough that he throws his entire life away and leaves his family for a doomed religious quest, but it never comes through. (And let me make it clear that I don’t think this is the child actor’s fault: Isaac Andrews does a perfectly good job with what he’s given.)

After Moses returns to Memphis and reunites with the Hebrews, he teaches them terrorist tactics to coerce the Egyptians into freeing them. (Again, this isn’t in the book.) These don’t work, and result in more public executions. After seemingly weeks of this, Moses finds God outside of a cave, and the following exchange happens:

Moses: Where have you been?

God: Watching you fail

Geez, try to be a little more supportive, God. Then God begins ranting at Moses about how horrible the Egyptians are, and how the Hebrews have suffered under 400 years of slavery and subjugation, which sort of just inspires a modern audience member to ask, “So why didn’t you intervene before, if this made you so angry?” but Moses turns it back on himself, asking what he can do. At which point God literally says, “For now? You can watch,” and then starts massacring Egyptians. Moses then, literally, watches from the rushes as the Nile turns to blood and various insects and frogs begin raining down, rather than having agency as he does in the Bible.

You need the sense of constant conversation between Moses and God, the push and pull between them that shapes the entire relationship between God and his Chosen People. And for that you need a sense of Moses choosing back. In the Book of Exodus, Moses’ arc is clear: he resists God’s demands of him, argues with Him, tells him he doesn’t want to be a spokesperson, cites speech impediment, pretty much whatever he can come up with. In response, God makes his brother, Aaron, the literal spokesperson for the Hebrews, but he doesn’t let Moses off the hook: he becomes the general, the leader, the muscle, essentially—but he’s also not a blind follower. He argues for the People of Israel when God rethinks their relationship, and he wins. He is the only human God deals with, and after Moses’s death it is explicitly stated that “there arose not a prophet since in Israel like unto Moses, whom the Lord knew face to face.”

In Ridley Scott’s Exodus, Moses fears God immediately, but he comes around to a genuine sense of trust only after they’re at the shores of the Red Sea. Knowing that the Egyptians are bearing down on them, the Hebrews ask Moses if they have been freed only to die in the wilderness, and at that moment, as an audience member, I really didn’t know. I had zero sense that God cared about them as a people rather than as a convenient platform for inexplicable revenge against the Egyptians. Moses, realizing that they’re doomed, sits down at the sea’s edge and apologizes, saying that he knows he’s failed God, and only after this does the sea part. This seems to be more because of currents shifting than an act of divine intervention… because, remember the other thing everyone expects from an Exodus movie? The Parting of the Red Sea, perhaps? This movie doesn’t completely do this: the parting happens, technically, but it’s totally out of Moses’ control, and could just be a natural phenomenon.

The film skips ahead to The Ten Commandments, where we find out that God is asking Moses to carve them out in reaction to Infamous Calf-Worshipping Incident, rather than before it. This retcons the Ten Commandments, tying them to a specific incident punishment rather than guidelines that exist outside of time. And God’s reaction to that infamous Calf? A disgusted shake of his head. Like what a pre-pubescent kid brother would do listening to his big sister gush about a boy she really liked. And all of this could have been awesome, actually, if the film had a thought in its head about an evolving God, a God that lashed out at some types of oppression but not others, a God that changed His mind as time passed. You know, like the one in the Hebrew Bible.

What does it mean to be God’s chosen? This question has been explored in literature from The Book of Job to Maria Doria Russell’s The Sparrow. Buried within the books of Exodus, Deuteronomy, and Leviticus is the story of Moses’ relationship with God. Most of the books of the Hebrew Bible don’t have the sort of emotional nuance and psychological development that a modern reader expects, simply because these are cultural histories, telling huge stories, giving laws, and setting dietary restrictions that span centuries. They can’t really take the time to give everybody a stirring monologue. Despite that, the story of God and Moses does come through in the Book of Exodus, and this is where the film could fill in Moses’ inner life. Christian Bale, who can be a magnificent actor, only really lights up when he’s playing against María Valverde as Moses’ wife. The moments when he has to deal with God, he’s so hesitant and angry that you never get the sense that there’s any trust or awe in the relationship, only fear. In an early scene, Moses defines the word Israel for the Viceroy, saying that it means “He who wrestles with God” but there’s no payoff for that moment. Moses goes from being terrified to being at peace with his Lord, seemingly only because his Lord lets him live through the Red Sea crossing.

Now, if we can wrap our heads around a single person being God’s Chosen, then what about an entire people? While Exodus can be read as the story of the relationship between Moses and God, The Hebrew Bible as a whole is the story of God’s relationship with the Hebrews as a people. From God’s promise not to kill everyone (again) after the Flood, to his selection of Abraham and Sarah as the forefathers of a nation, to his interventions in the lives of Joshua, David, and Daniel, this is a book about the tumultuous push and pull between fallible humans and their often irascible Creator. However, as Judaism—and later Christianity and Islam—spread, these stories were brought to new people who interpreted them in new ways. Who has ownership? What are the responsibilities of a (small-c) creator who chooses to adapt a story about Hebraic heroes that has meant so much to people from all different backgrounds and walks of life? To put a finer point on this, and returning to my thoughts at the opening of this review: is Exodus racist?

To start, the statuary that worried me so much in the previews is clearly just based on Joel Edgerton’s Ramses, and they left the actual Sphinx alone. That said, all the upper-class Egyptian main characters are played by white actors. All of ‘em. Most of the slaves are played by darker-skinned actors. The first ten minutes of the film cover a battle with the Hittites, who are clearly supposed to look “African,” and are no match for the superior Egyptian army.

Once we meet the Hebrews we see that they’re played by a mix of people, including Ben Kingsley as Nun (the leader of the enslaved Hebrews and father of Joshua) and Aaron Paul and Andrew Tarbet as Joshua and Aaron respectively. Moses is played by Christian Bale, a Welsh dude, mostly in Pensive Bruce Wayne mode. His sister, Miriam, is played by an Irish woman (Tara Fitzgerald). Now, I am not a person who thinks we need to go through some sort of diversity checklist, and all of these actors do perfectly well in their roles, but when you’re making a movie set in Africa, about a bunch of famous Hebrews, and your call is to cast a Welsh dude, an Irish woman, and a bunch of white Americans? When almost all of the servants are black, but none of the upper-class Egyptians are? When John Turturro is playing an Egyptian Pharaoh? Maybe you want to rethink things just a little.

(Although, having said that, John Turturro’s Seti is the most sympathetic character in the movie. But having said that, he dies like ten minutes in, and you spend the rest of the film missing him.)

The other pesky racially-tinted aspect of the film is that the poor Egyptians are suffering about as much as the Hebrew slaves, and it’s extremely difficult to listen to God rail against slavery and subjugation while He’s pointedly only freeing one group from it. All the black servants will still be cleaning up after their masters the day after Passover. The Exodus story became extremely resonant to the enslaved community in America, and was later used by abolitionists to create a religious language for their movement. Harriet Tubman was called Moses for a reason. So to see a black character waiting on Moses, and knowing that he’s only there to free some of the slaves, becomes more and more upsetting. This feeling peaked, for me, when the 10th plague hits, and you watch an African family mourning their dead child. Given that the only obviously dark-skinned Africans we’ve seen so far are slaves, can we assume that this a family of slaves? Was the little boy who died destined, like the Hebrew children, for a life of subjugation? Why wasn’t he deemed worthy of freedom by the version of God this film gives us?

This just brings up the larger problem with adapting stories from the Hebrew Bible and New Testament, though. These stories adapt and evolve with us. When Exodus was first written down, it was a story for the Hebrew people to celebrate their cultural and religious heritage—essentially the origin story of an entire nation. It was a story of their people, and explained them to themselves. It reaffirmed their particular relationship with God. As time passed, and Christianity ascended, the story of Passover particularly was used to bring comfort to a people who were now being subjugated, not by foreigners or infidels, but by people who claimed to worship the same God they did. The story then transmuted again as enslaved Africans, indoctrinated into Christianity, applied its teachings to their own situations, and drew hope from the idea that this God would be more just than its followers, and eventually lead them out of their own captivity. In light of this history, how can we go back to the old way of telling it? How can we tell a tale of a particular people, when the tellers themselves seem more invested in making the plagues scary and throwing 3D crocodiles at us? How can this be a story of freedom when so few of the slaves are freed?

If we’re going to keep going back to Biblical stories for our art, we need to find new ways to tell them, and dig in to look for new insights. Darren Aronofsky’s Noah also strayed pretty far from its source material, but in ways that added to the overall story. It makes sense that Noah is driven mad by the demands of the Creator. He also dug into the story to talk about ecology, our current environmental crisis, and the very concept of stewardship in a way that was both visually striking, and often emotionally powerful. It didn’t always work, but when it did, he made a movie that was relevant to humans right now, not just a piece of history or mythology. If you’re going to make a new version of a story of freedom, you have to take into account what this story has meant to thousands of people, and what it could mean to us now rather than turning it into a cookie cutter blockbuster with no moral stakes or purpose.

Perhaps Leah Schnelbach is naive, but surely there are one or two capable actors in Egypt? You can choose to follow her on Twitter!

I’m interested in how our reaction to the story will continue to evolve. The premise is a powerful one, but I have trouble reonciling it with a history that strongly suggests it didn’t happen anything close to the way the source material depicts it.

I’d like to see an Exodus that tries to reconcile the Biblical story with more of what we know from history. It appears that the monument builders in ancient Egypt were not usually slaves, and not entire ethnicities of immigrants. It might be interesting to see how a filmmaker uses the information that the Hebrew yam suf can better be translated Reed Sea than Red Sea.

“Why make weird gestures towards a critical perspective on the Exodus story but then cast your Egyptian and Jewish characters with white actors?” In all the weeks and weeks of this controversy has no one pointed out to you that Egyptians and Jews are, in fact, white?

A straight retelling of the Exodus story would be almost impossible, because modern audiences aren’t quite ready yet to watch the deaths of the first-born children of every family in an entire country and think of the character who murdered them as the good guy.

The other pesky racially-tinted aspect of the film is that the poor

Egyptians are suffering about as much as the Hebrew slaves, and it’s

extremely difficult to listen to God rail against slavery and

subjugation while He’s pointedly only freeing one group from it.

Again, this is a problem with the source material, not the film. You really can’t read the Old Testament and think “God cares for everyone equally!”

And you really can’t read the New Testament and think “God disapproves of slavery”, for that matter. God spends plenty of time in the New Testament talking about how evil it is to get divorced, or how he’s going to enjoy torturing you for ever after you die if you don’t give enough to charity while you’re alive, but there’s not a second to spare – and how easy it would have been! – for him to add something like “Do not keep your fellow humans as slaves, whatever their nation or religion. Do not enslave them, or buy or sell them – this is abominable to me. If you already hold slaves, free them, and employ free labourers at a fair wage instead.”

Herb9200, while modern day Egyptians are largely of middle eastern stock, during the 3,000+ year history of Egypt it was repeatedly conquered and occupied by various ethnic groups, from Africa. The Egyptian royal family after Alexander the Great was of Greek descent, but Ramses II was an Egyptian, and incredibly inbred, and would not have looked like blue-eyed Joel Edgerton.

I haven’t seen the movie but this an interesting review. I’m troubled, though, by the way the film seems to be trying to present itself as a more ‘realistic’ take on biblical history, when this sounds like just as much a fantasy as Charlton Heston’s Ten Commandments. There is nothing wrong with that necessarily, but somehow it seems dishonest to me to present this story in such a grisly way–like it is trying to give itself a veneer of truth that it does not earn.

Also why would the Hittites be portrayed as African? Gosh.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Plagues_of_Egypt#Historicity

They cast a child as God. They cast a CHILD as GOD. Um. I don’t want to see this film anymore. Ugh.

Dreamworks’ Prince of Egypt tried very hard to remain well inside the realm of PC by attempting to appease the major religious groups and incorporating various aspects of those religions’ beliefs into their film. And you know what? It’s a fantastic movie. I’m religious and I loved it. My non-religious friends loved it. It was a love fest.

Based on this review, it seems like Exodus is attempting the exact opposite and intentionally goes the un-PC route. I suppose controversy can be fun every now and again, but playing around with religious narratives can be incredibly dangerous. When you’re futsing with a text and story that’s spiritually meaningful to billions of people and spiritually meaningless to billions more, it’s very, very easy to offend on a high level. And I’m feeling slightly offended.

@5: I’m not sure it’s trying to present a more “realistic” view of the Bible. It seems, from everything I’ve heard, to be kind of a natural extension of the sort of pseudo-scientific half-Christian creationist fantasy hokum that Ridley Scott was so confused about in his direction of Prometheus.

They cast a child as God. They cast a CHILD as GOD. Um. I don’t want to see this film anymore. Ugh.

I’m curious why this, in particular, was a dealbreaker. Would it have been more acceptable to cast, say, a slightly portly middle-aged man as God?

Say this for the old biblical epics, they normally steered clear of that sort of thing altogether…

In all the weeks and weeks of this controversy has no one pointed out to you that Egyptians and Jews are, in fact, white?

Race is of course a social construct and there’s no such thing as an objective definition of who’s white and who isn’t – it’s not so long ago that the Irish weren’t considered white, for instance – but I am still a bit startled that there’s someone out there who thinks that Egyptians are generally considered white. Non-black, yes. But it’s not quite the same thing.

I hardly think this is “racist” in the sense that the movie is saying one race is inferior or that it exhibit hatred for a race.

It’s simply telling the story of Exodus, which is about the Jews being set free. The story of the other slaves is not the story of Exodus.

As for the white actors, it certainly would be nice to see a more diverse, historically accurate cast. But when throwing around hundreds of millions of dollars to make this movie, they need big names to back it up. When you foot the bill, you can cast who you like. But I am certainly not going to tell anyone how to spend their money.

And that includes moviegoers. Vote with your wallet and don’t see this if bothers you. But without those big name actors as insurance, this movie doesn’t get made to this scale.

Not that this is a movie I ever intend to see, but the outrage over casting a CHILD as God kind of cracks me up, given that we are in the middle of Advent right now…

(And yes, I know there are some thematic differences in the way God manifests himself in the Hebrew Bible and the New Testament that do make it a little ridiculous to portray God as a child in this particular story but it made me chuckle a bit).

Ramses II was an Egyptian, and incredibly inbred, and would not have looked like blue-eyed Joel Edgerton.

You’re right. Joel Edgerton has black hair. Ramses II looked like, well, let’s quote the wiki on what they found from his mummy…

The pharaoh’s mummy reveals an aquiline nose and strong jaw, and stands at about 1.7 metres (5 ft 7 in)… the hair is quite thick, forming smooth, straight locks about five centimeters in length…

Microscopic inspection of the roots of Ramesses II’s hair proved that

the king’s hair was originally red, which suggests that he came from a family of redheads…

And here’s a picture of the man himself, as reconstructed:

http://mathildasanthropologyblog.wordpress.com/2008/07/24/egyptian-mummy-reconstructions/

Ramses II actually looked even less like a typical modern Egyptian man than Joel Edgerton does!

The “God as Child” thing strikes me as a kind of modern horror film influence. It’s inherently creepy if a child is talking like an adult. That’s why those etrade baby commercials are the most disturbing advertisements known to man.

Anyway Scott is probably just using that for effect. I suppose he could have been influenced by all of those old medieval paintings where the infant Jesus has a baby’s body but an adult head though…

I would point out by the way that the excuse of “Big budget films aren’t going to take a risk on unproven actors” is just about the weakest excuse for racist hiring practices possible. It’s like, a non-excuse. Like, you couldn’t get away with that in any other profession. The only reason Hollywood gets a pass is because of the artistic nature of the work; it blurs the line between labor and artistic expression, and no one wants to be seen as engaging in censorship.

But when people justify using white people in minority roles on the basis of dollars and cents, you’re really giving away the whole game; “We’re not racist but we have to market our films to racists or we wouldn’t make lots of and lots of money.”

Romans=British actors and Jews=American actors isn’t a trick of commentary that’s original to Scorsese, the tv mini-series of Masada is just one previous example.

Please don’t say “Brit”, unless you’re putting it in ironic quotes, or matching the tone with “Yank”. You wouldn’t comment on the “Jap” actors in a film.

Casting God as a child is a fantastic conceit, actually, especially if you couldn’t easily determine whether it was a boy or girl. I’m sorry it didn’t work out in this case.

I’m also sorry, Colin @14, about how wrong you are re the eTrade baby commercials. All right thinking people know they are the greatest TV commercials ever made — especially the first wave — and that “Shankapotomus” is the best commercial punchline. Evar.

(Also, also, @17: “eyeroll”.)

“Without those big name [white] actors, the movie doesn’t get made at all.”

Maybe, and here’s a thought, just maybe, it shouldn’t have been.

“Without those big name actors, the movie doesn’t get made at all”

Let’s say I accepted this argument as true(I don’t*).

This is, as Patton Oswalt put it, “a crazy Christian country”. America loves biblical movies. Passion of the Christ made 600 million worldwide, over 300 million in the US alone. And they don’t even speak English in that movie.

So if ANY movie could get away from “must have a bankable white star or it won’t do well” stigma, it’s THIS ONE.

*It’s one of those arguments that prove itself. You state “Movies that star POC don’t succeed”(ahem) and studio execs listen, and don’t cast POC is blockbusters, and guess what. The narrative has fulfilled itself.

I’m white, and I’ve been mistaken for a Turk by Turks in Turkey. I dare say I could fit in in Egypt as well. But I would never be mistaken for an Ethiopean or Nigerian.

So I have no problems with a white actor portraying an Egyptian. What surprises me is the idea that the Hittites were supposed to look African. The Hittites came from Anatolia – in modern Turkey.

@20: I’m surprised to see that link goes to The Scorpion King — not because it wasn’t successful. Rather, just because I’d forgotten about it. But the list isn’t exactly a short one, in either case.

Big Hero 6

Ride Along

The Butler

12 Years a Slave

Pick Your Tyler Perry Movie

Men In Black (1-3)

Life of Pi

Slumdog Millionaire

Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon

Puss N’ Boots

The Karate Kid (2010)

The Book of Eli

The Princess and the Frog

And so on and so on

@22, I went with an older one on purpose. IMO, it was kind of the “first” POC led action blockbuster that I can recall, that wasn’t flat out exploitation(though it did have it’s issues(British Dude conquers North Africa, Imports Asian Chick).

And that wouldn’t have happened without the stunt casting in The Mummy 2(which is why I don’t look askance at attempts to increase diversity by piggybacking off more well known properties, like Thor and Captain America)

Ah, good point. I hope my list adds to it by highlighting different kinds of representation. There are POC from a variety of backgrounds. There are live-action movies starring POC there, but also animated movies where the main characters are visibly POC, animated movies where the lead character is simply voiced by a POC, dramas, foreign language films, blockbosters, small-budget films that succeeded on word of mouth, movies with no white people at all, comedies, etc. Death at a Funeral also comes to mind, a movie that made more money worldwide with a black cast (2010) than with a white one (2007).

miriam12 @7:

“They cast a child as God. They cast a CHILD as GOD. Um. I don’t want to see this film anymore. Ugh.”

I actually buy a child as God this early in the Hebrew Bible. More than one commentary has been written about how God himself seems to grow and mature as the book’s pseudo-history progresses.

@21 — Turks are Caucasian (as are Persians, and so on). Arabs, I have recently been informed in no uncertain terms, are Afro-Semetic. You might conflate them, but I suspect the groups in question most emphatically would not.

People are complex.

@@@@@ 21, 26 — an interesting piece from a necessary perpsective:

http://bloglikeanegyptian.tumblr.com/post/104734246271/before-talking-about-egypt-post

@26: Wouldn’t that be a language-based classification? I don’t think that has anything to do with a discussion about facial features (and skin tones).

I was honestly willing to give the film the benefit of the doubt regarding casting–the mummy of Ramesses the Great is said to have red hair, and the upper class of Egypt likely spent a lot less time in the sun than did the peasantry. Of course, the Jews ought by that token be a fair bit darker than the Egyptians…

Anyway, what finally made me agree with the “whitewashing” criticism was the mention of African-looking Hittites. Hittites were actual Indo-Europeans. Most scholars say that Indo-Europeans emerged in Ukraine. Even assuming the Indo-Europeans were just a small overclass, one would expect the Hittites to at least look Assyrian. If anyone in this film should look white, it’s the Hittites!

This is an interesting idea, and could have resulted in a moving film, but since he doesn’t fully commit to any one thing, the film sort of turns into a weird stew.

Yeah, like Robin Hood, Prometheus and The Counselor. You’re on a roll, Ridley!

30 is a good and depressing point. I remember reading a description of the early version of the script for Alien and it was a hideous mess of exactly that type – there was a pyramid, and another alien species that worshipped the Aliens, and so on. All of it was cut for budget reasons. Maybe the problem is that Scott’s now doing films that have budgets big enough to allow him to do what he wants.

I haven’t seen the film, so I dont know the details, but the wedding vows may be accurate. A traditional Jewish marriage contract, called a ketubah, often specifies that couples must physically satisfy each other as well as emotionally support each other (the whole “in sickness and in health” bit). It was a bit embarrassing when mine was read out at our wedding.

As for race, the Hittites were northern, so they should not have been African. But the upper class Egyptians should definitely have been of mixed race, as Egypt’s lower kingdom was modern-day Somalia and Ethiopia. Pharoh himself would have exhibited recessive genes: red hair, and possibly blue eyes. The Israelites would have looked much like their masters, since they interbred quite a bit, but may have shown their Iraqi ancestry (more like Indian than anything else). Other slaves would have been a mixture of white and black, though skewed towards the white side, since the Egyptians fought more with the north than south. Thus we get the modern Middle Eastern race, which is a mix of Caucasian, African and Indian.

I’m white, and I’ve been mistaken for a Turk by Turks in Turkey. I dare

say I could fit in in Egypt as well. But I would never be mistaken for

an Ethiopean

Yeah, don’t be too sure. This guy was Ethiopian.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Haile_Selassie

I wasn’t really planning on watching this movie anyway but this clinches it. I’ll stick with my The Ten Commandments, which is a near perfect movie in my opinion.

The part that bothers the most for me is the indecisiveness about if Moses is delusional or not. I’m a believer so I would prefer the God really did all this telling but if they went a completely naturalistic way to explain everything I could respect that. But standing in the middle is trying to appease both sides and not succeeding. I know modern audiences love to have room for doubt, but for this story I would think you’d either embrace the divine or reject it entirely. I mean the Ten Plagues are a giant assault on Egyptian Theology that literally killed the sacred cow and to have that be boiled down to “well it could have been God or just a huge chain of coincidences ” rings hollow.

The other problem is the racial casting. Yes, I know that The Ten Commandments didn’t do well with this aspect (though at least it had some fantastic actors) it actually was made in a time when it couldn’t be done. Off the top of my head I would have had either Idris Elba or Alexander Siddig as Ramses. While neither of them may have actually looked like the real Ramses, it fits in with the perception of the time.

While neither of them may have actually looked like the real Ramses, it fits in with the perception of the time.

It would be less problematic to have provably inaccurate casting because it would fit in with most people’s completely erroneous beliefs? Er…

#31

Yeah, I think so too. Seems to be a problem with a lot of these big blockbuster type movies now, they’ve got too much money and options available. Then you have filmmakers being bombarded by demographics and studio notes. It’s really no surprise so many of these flicks end up “weird stews” that can’t fully commit to one vision.

@35

Yes because it does away with even the perception of racism. This is Hollywood after all, no one is looking for complete historical accuracy but a fantastical facsimile. You know like the fact that The Tudors didn’t have Henry at the correct age or waist line for when he met Anne Bolyen. Documentaries and history books give you the facts, movies are about the dream. So if you can cast a great actor without the appearance of white washing that’s what you go for. And considering what has been said of the Hittites I don’t think accuracy was what the powers that be had in mind when they cast Ramses.

Ridley Scott admits that he is an atheist. An important question is, why did an atheist accept the challenge of making a biblical movie? The answer is, unfortunately, that he did it in order to advance atheism. Consider this, dear reader: as you will learn if you see or read about the movie, Scott provides “scientific”, or atheist, explanations for every miracle, every plague, even for Moses’ meeting with God. That is, Scott advances militant atheist arguments throughout the movie, suggesting that the parting of the sea had a natural cause, the plagues had these natural causes, Moses only imagined that he talked to god, etc. The director’s interpretation of the Exodus story is completely consistent with his own point of view as an atheist, and is completely opposed to the Bible itself. If you saw the movie, the truth would be obvious to you: the atheist director made the movie in order to promote an atheist view of the Exodus story. That is the movie’s clear purpose.

@Jonathan “Gott”

Assuming your assumption is true, why would it be bad for an atheist to promote his own views? Is it better if a theist uses a movie to promote the theistic world view?

@38

I agree with Kah-thurak, there’s no problem with an atheist view of the Exodus story, provided you stick to that. Come up with some conceit for the plagues being man made (maybe with the act of terrorism that was mentioned in the review) and you have a great historical epic I’d gladly lose myself in but I don’t like trying to have your cake and eating it too.

I don’t have a problem with an atheist making biblically-inspired stories from an atheist perspective. I do think it’s pretty weird to start with the assumption that the basic framework of biblical stories are true, and come up with naturalistic explanations for fantastic stories. That feels like the same impulse as goofy arkeologists. Like, if it was actually atheistic propanganda I have to imagine it’s not going to be very successful. Unless your only purpose was to annoy biblical literalists.

@38, I happen to know a great many Christians who believe “that the parting of the sea had a natural cause, the plagues had these natural causes, Moses only imagined that he talked to god, etc.”

Do you think they are pushing a militant atheist agenda?

#38 – I’m going to go with the idea that he made a movie to make money, not to promote some atheist point of view. I know it sounds crazy, but, there it is.

What is a militant atheist anyway? Do they sing “Onward NonChristian Soldiers”?

I think one thing that may have people confused about what the Children of Israel would have looked like is the appearance of the Ashkenazi descendants who currently occupy Israel and have barely a drop of Semitic blood in them… but I’m pretty sure Jews 3500 years ago didn’t look mostly white….

Scott lost me when he named the Pharoah. The Bible does not name the Pharoah and the two things that let us date the Exodus (a fragment with the name Jacob and the datating of the destruction of Jericho), both place the story long before there was a Pharoah named Ramses. The Bible says the Hebrew slaves built the cities of Pithom and Ramses and there is no evidence that the city was named after the Pharoah and it could have been the other way around. But add to that personal gripe of mine all the things mentioned that Scott did in this movie and I no longer have any interest in seeing it. I usually take reviews with a grain of salt (I think the reviewer was being overly sensitive to race in how the movie was cast), but there are too many hard details, not just opinions, here to ignore.

General consensus among archaeologists is that the Exodus never happened, so saying they got the Pharaoh wrong is a bit odd…

Thanks for the review.

– Tha plagues were a response to the eygptian gods and their so called power. Each one was designed to insult and scare the eygptians and their idol worship, to prove to them that Isreal God was real and more powerful.It was also designed to show the Isrealites that the God of Jacob exsisted and to stop worshiping the Eygptian gods. That whole golden calf thing wasn’t out of the blue, but because they had fallen into worshipping idols as well.

-The thing many people don’t seem to get is that these plagues were throughout the LAND of Egypt. It wasn’t just one city or small patch of land hence the devestation of the plagues. I doubt natural occurance could explain how a whole country at the time suffered the same from one area to the other area.

-There doesn ‘t seem to be a time frame for the plagues. No one knows if they took a whole year or were just quick one after another. Either way Egypt was devestated by the end of them.

-It’s the firstborn of every house hold, not just the children who died in the last plague. That means full grown adults , men and women, girls and boys were dying as well as their animals. Folow this with the whole Egyptian army getting wiped out with the sea and suddenly you have very little to no recurits for several years to defend Eygpt.Coupled with them opening up thier tresury and giving all thier valuables to the Jews and this country is devestated on all levels.

-Moses was at least 80 yrs old when he came back to Eygpt. Not one depiction of this has ever addressed this issue. Joshua was his military leader for a reason along with Caleb. Now he could have been a robust 80 yrs old but still he wasn’t doing sprints or riding on horse back leading armies.

– It’s debated but it seems that Moses had two wives during his life. First Zipporah a Midian and then an Eithiopian wife later on. By the time the Eithiopian is mentioned Moses is probably around 100 yrs old. Zipporah would probaly be dead by then even if she was slightly younger given the hardships women faced back then. Not to mention the fact that Z wasn’t a follower or at least reluntant to follow Moses God. In fact Zipporah went back to her home after Moses sent his family away when he continued on to Egypt. He didn’t see her until they were out in the wilderness.From the sounds of it it was a troubled marriage.