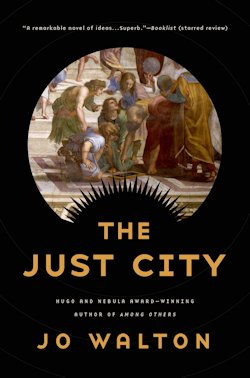

There’s a touch of time travel in The Just City, and a rabble of robots that may well be self-aware, but please, don’t read Jo Walton’s thoughtful new novel expecting an exhilarating future history, or an account of the aggressive ascent of artificial intelligence. Read it as a roadmap, though, and this book may well make you a better person.

A restrained, if regrettably rapey fable with a focus on exposing the problems with philosophy when it’s applied as opposed to lightly outlined, The Just City takes as its basis a certain social experiment proposed by Plato:

The Republic is about Plato’s ideas of justice—not in terms of criminal law, but rather how to maximise happiness by living a life that is just both internally and externally. He talks about both a city and a soul, comparing the two, setting out his idea of both human nature and how people should live, with the soul a microcosm of the city. His ideal city, as with the ideal soul, balanced the three parts of human nature: reason, passion, and appetites. By arranging the city justly, it would also maximise justice within the souls of the inhabitants.

That’s the idea, at least. Alas, in reality, justice is far harder to achieve than the great Greek believed.

When a nymph named Daphne opts to be turned into a tree rather than share in eros with the god Apollo, said son of Zeus turns to Athene, the goddess of knowledge, to find out why the woman went to such lengths to avoid his affections. By way of explanation, Athene invites Apollo to participate in a realisation of the Republic. He takes her up on her offer by taking on the form of a mortal boy called Pytheas: one of ten thousand ten-year-olds “saved,” as their new masters would have it, from a life lacking liberty.

Simmea comes to the just city Athene teases into being with hope in her heart—hope that here, by learning to live according to Plato’s principles, she can be her best self. She and Pytheas soon form a fast friendship; a friendship Kebes, who met Simmea at the slave market on the day their contracts were bought, and thinks Pytheas preternatural, simply cannot countenance.

But wait, what’s this? Jealousy in the just city, where no one person is to possess, or be possessive of, another? “The ship was barely out of the harbour [and] already the seeds of rebellion were growing.”

Maia is the third of The Just City’s three POVs: a nineteenth-century Yorkshire sort so struck by Plato’s beliefs about the education of women in the world that she wishes, one day, that she could leave her life behind, the better to pursue Excellence in such a perfect place. Unexpectedly, Athene hears her prayer and makes Maia—along with a couple of hundred other philosophical pilgrims plucked from the whole history of humanity—a master.

The masters’ first charge is to build the city for the children to live in. This gives us an opportunity to revel in the text’s superlative setting—“a sterile backwater of history” it may be, but the ill-fated island of Kallisti is alive with promise and possibility—and glimpse of a couple of characters who come into play in a major way later. Unfortunately, Maia’s chapters lag distractingly, isolating her perspective from the other pair by a period of years and disrupting the gathering of the larger narrative.

Walton is wise, in that regard, to compel through character as opposed to plot—of which there’s not, if I’m honest, an awful lot. That said, at the same time as telegraphing some of the more interesting developments ahead, The Just City’s diversity of perspectives serves to keep readers on their feet.

And the three threads do come together eventually, to their creator’s credit. Indeed, Sokrates’ appearance signals a turning point in the novel, on the back of which the book goes from getting-there to great. “He’s like a two-year-old sticking pencils in his ear” at points, yet the fellow is fantastic fun from the first. Compelled to come to Kallisti against his express assertions, the closest thing history has to a philosopher king resolves right away to ruin the Republic—and in the very way one imagines he would: by exposing the problems with its premise through dialogues with everyone (and everything) in the city. Even Maia, who flits around the periphery of the fiction, shares a moment of some significance with Sokrates.

He, then, is the glue that finally binds this book. Without him, it’s a clever question asked of an empty auditorium, but when at last an audience arrives—and with them, the chance of an answer—The Just City is a wonder, as wise as it is witty; a party which rattles along happily until the evening’s over, never mind the absence of incident.

Actually, I take that back. There is incident in The Just City. Several variations on the same incident, I’m afraid, which—whilst well handled—come with a whopper of a trigger warning. There’s such a superabundance of intellectually illustrative sexual violence in this otherwise understated affair that I wish Walton had worked harder to find other ways of exploring free will and equality for all.

Some will have a harder time than others putting aside that oversight in addition to the first act’s failings, but those who do push through can count on a considered account of character and morality that mixes fantasy with philosophy and history with the stuff of science fiction. “It was full of variety and yet was all of a piece. Nobody could ask more.”

It’s with reservations that I recommended The Just City, but I do, to be sure.

The Just City is out from Tor Books on January 13, 2015.

Niall Alexander is an extra-curricular English teacher who reads and writes about all things weird and wonderful for The Speculative Scotsman, Strange Horizons, and Tor.com. He’s been known to tweet, twoo.

I have this on pre-order-really looking forward to diving into it.

I am looking forward to this too, although this isn’t the first “with reservations” review I’ve seen.

I wish Walton had worked harder to find other ways of exploring free will and equality for all.

This isn’t the first review I’ve read to talk about this as if it were an accident, or a disposable element of the premise, whereas it felt to me like being about consent to sex specifically was right at the core of what the book was doing, in ways that are rare to see engaged with at all, and derfinitely worth having even if clearly not for everybody.

re: #3 — yes. The book I read was explicitly, centrally, and completely about consent.

@3,4 – Exactly. Consent and volition are central themes. Sexual violence is a particular example of that, and one that resonates strongly throughout the book, but there are plenty of other examples including the circles of the gods Apollo mentions, to the status of the children in the City, and all the way down to the workers. The whole thing’s a meditation on control/consent. I think there are plenty of novels where you can say rape’s used as a cheap plot driver, but in this case it’s as integral to the book as could be.

Great review. One of the biggest reasons I’m still formulating my own is I’m still trying to nail down my respone to those rape scenes. Even while agreeing they have clear thematic connections/reasons for being, I still find some aspects of their portrayal to be problematic. Beyond the obvious fact that they are meant to be problematic generally, as they might also be in those particular aspects I’m having difficulty with and (hmm, did I mention I’m having difficulty naling this down?).

But regardless, definitely a recommended read for its thoughtfulness. And I’m in full agreement about Sokrates’ impact. I’m looking forward to the follow up in a few months

“The Philosopher Kings”, Tor, June 30, 2015?

Delong: Yes, The Philosopher Kings is a sequel, and I am working on a third one.

I thought the scenes fit within the story and the general framework well. Apollo’s quest to understand why Daphne would choose to turn into a tree rather than accept his rape–framing the importance of consent from the very start establishes this.

The general concept of the Greek gods and mythology also stands as backgorund to this. The general mythology base is rife with problematic issues and I see part of this story as a response to those myths.

How this framing interacts with the idealism of the Republic and the attempts at its enactment are very interesting.

Sokrates is a wonderful element. I quite prefer the Sokrates here to the version given us by Plato.

Being bothered by the scenes is, I think, quite a healthy response but I also thing that they work.

Let’s see now. This is a book that has slaves and Greek mythology. And the complaint is that there is a superabundance of rape? Has nobody read Greek myths before? Are the Greek tragedies tragically forgotten? Do slaves have voluntary sex?

Maybe we instead needed Jo to provide us more relative ease in our reading with incest (Zeus and Hera? Oedipus and Jocasta?), patricide (e.g., Oedipus and Laius, or better yet, Pelias being torn apart by his daughters), furious matricide (e.g., Orestes, Electra, and Clytemnestra), and even give us our fill of filicide (e.g., Medea, Tisander and Alcimenes)? Oh wait, I know the answer! Let’s have Rick Riordan write for us the sanitized Percy Jackson version of the Ad-justed City! That will knock our “Soks” off!

Come on folks—it’s impossible to read unadulterated Greek mythology without encountering a superabundance of violence of all types, including rape. And remember, myth is allegorical; it is symbolic. We are dealing with archetypes. This is the stuff of real literature.

The mere act of writing about something, even a superabundance of that something, does not glorify that something. Sometimes oversaturation may even be the antithesis of that. If you don’t want to read a story that has a lot of rape in it, then maybe you shouldn’t talk about rape so much either. Let’s avoid examining something that is offensive and demeaning and uncomfortable to discuss. Because that (examining) is what Jo is doing. If you can’t talk about it, who’s to say it exists and needs to be eradicated?

Puntificator @10

My issue with the rape scenes were not that there were rape scenes or that I “encountered” violence. I didn’t go into details because

a) pragmatically I didn’t want to spoil scenes for those yet to read the book and more importantly

b) as mentioned, I’m still trying to think through the issues. Why? Because they are complex. Hardly the simplistic response of “My gosh, there is violence and rape in the world. Ewww.” And I appreciate the author creating such complexity so that I have to actually think things through as to how and why I’m responding to such scenes. I far prefer that kind of writing rather than the sort that uses rape, violence, or any other such act as a cheap tool for “impact.”

I’m looking throught the review and comments and I’m kind of lost as to where you thought anyone was accusing Jo Walton of “glorifying” rape, or saying authors/readers “can’t talk about it” or that people want to “avoid examining something that is offensive and demeaning and uncomfortable.” Finding other or different ways, as the reviewer suggested, might just mean in addition to a rape scene or two and not mean remove all references to rape and violence in favor of some more cheery method. Though I can’t speak to that with any sense of surety.

I also generally, when having a different take than another on some matter, prefer not to assume immediately that I come from some uniquely qualified position of knowledge—i.e. being the only one to have read Greek myths, to have remembered Greek drama, to have read any history–when someone has a different take on something, Especially in dealing with such basic knowledge and with a commentator base that in my experience is pretty well read and thoughtful. Far more interesting would be to explore the whys and wherefore of those different takes from an asumption of shared knowledge and thoughtfulness–far more intriguing than simple ignorance or a desire for banal comfort as the cause.

Bill,

I believe most of us (incl Puntificator #10)were referring to this section of the review:

Then, from comment #3-5 (including me) people basically said that it’s a central part of the novel’s main themes, and Puntificator took that point a lot further. I don’t think any of us are claiming the topic shouldn’t be discussed or claiming it’s being glorified in any way, but I do feel (speaking as a friend of Niall’s and a general admirer of his reviews) that that section of this review didn’t really do justice to what I think Jo is trying to do in this novel. I have to get around to writing my own review (and usually try to avoid getting into this type of discussion before that; ah well) but it’s probably clear that a good chunk of my interpretation would focus on the various ways in which free will and consent are illustrated in the novel.

Hey Stefan,

Yeah, I figured that was the section. I guess I saw it as more a minor preference than a wholesale misreading or glorification/desire for silence on the topic (which as you noted, neither you nor 3/4 argued). That said, I’m wholly with you on the idea that volition/free will is the overriding theme of this book, and that those scenes play directly and clearly quite purposely into that theme. It’ll be interesting to see the slew of reviews that will apparently be discussing this . . . :)

Bill@13:Yeah, this book should have some interesting discussion–see we’re already having one. :-)

Also–Sokrates and robots!

I don’t assume that I “come from some uniquely qualified position of knowledge—i.e. being the only one to have read Greek myths, to have remembered Greek drama, to have read any history.” I wouldn’t have made the references I did if I had such assumptions. I would say that someone who assumed I assumed that is (tautologically) making assumptions. What I was doing instead by asking the questions I did, was to make a sort of Socratic inquiry by using those questions in a satirical variant of Socratic irony, which I thought appropriate given the book’s use of Sokrates. I probably did so poorly, for I am no Sokrates. My mind is more like play dough.

I do indeed ascribe to the view that there is “a commentator base that … is pretty well read and thoughtful.” But they are not, in my opinion, demonstrating herein their ability to communicate to me, based on such a background, what the specific problem is with Jo’s allegedly superabundant use of rape scenes.

Sure, it’s fine to say: “Far more interesting would be to explore the whys and wherefore of those different takes from an asumption of shared knowledge and thoughtfulness.” Then please do so. Or, as Sokrates might say while feigning ignorance, “I don’t see why we should do so.” I was actually disappointed that I could not find where the article’s author or anyone else really said anything specific about the rape scenes other than there is a superabundance of them and they are “problematic.” It’s a classical case of ignorance on my part, for which I Apollo-gize.

I’m two thirds through the book; pretty great, so far. I find the connection Walton makes between the treatment of women throughout history (specifically the denial of scholarly pursuits and the prevalence of sexual violence), “classical” and more modern slavery, and AI rights fascinating. It’s all the same, on some level, which very little SF/F fiction acknowledges.