I remember the first time I encountered an attractive fat woman in a fantasy novel. My heart flipped a little as I read about a woman was for-real fat. She wasn’t your usual fictional overweight woman, either: there was no zaftig or curvy or voluptuous to be found near the Scientist’s Daughter in Haruki Murakami’s Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World. But she was definitely attractive. The narrator describes her as follows:

“A white scarf swirled around the collar of her chic pink suit. From the fullness of her earlobes dangled square gold earrings, glinting with every step she took. Actually, she moved quite lightly for her weight. She may have strapped herself into a girdle or other paraphernalia for maximum visual effect, but that didn’t alter the fact that her wiggle was tight and cute. In fact, it turned me on. She was my kind of chubby.”

She was chubby and attractive. It wasn’t ideal representation, not by a long shot, but it was something in a land of so very little. The description was imperfect but refreshing. For a fantasy fan like me, finding a fat, attractive female character felt revolutionary. Maybe it hit hard because it was my first time. I was 19 when I read Hard-Boiled Wonderland, which means it took me almost 15 years to find an unconventionally attractive woman in a fantasy novel who was not a mother, villain, or whore. And I had to go speculative to get it.

An avid childhood reader, I grew up on a steady diet of sword-and-sorcery. This meant a parade of maidens that were comely and lissome, which is fantasy slang for pretty and thin. I was really into the Forgotten Realms series for awhile—I’d buy as many as I could carry at Half-Price Books, and settle in with descriptions like this, from Streams of Silver (Part 2 of the Icewind Dale trilogy):

“Beautiful women were a rarity in this remote setting, and this young woman was indeed the exception. Shiny auburn locks danced gaily about her shoulders, the intense sparkle of her dark blue eyes enough to bind any man hopelessly within their depths. Her name, the assassin had learned, was Catti-brie.”

As our heroes journey a little further, they encounter a woman of easy virtue. She is described this way:

“Regis recognized trouble in the form of a woman sauntering toward them. Not a young woman, and with the haggard appearance all too familiar on the dockside, but her gown, quite revealing in every place that a lady’s gown should not be, hid all her physical flaws behind a barrage of suggestions.”

In the land of the dark elf Drizz’t do Urden, not only are good women beautiful, plain women are bad. They are beyond bad—they are pitiable. To be physically imperfect, overtly sexual, middle-aged is to be ghastly, horrid, wrong. Streams of Silver feels dated, but it was published in 1989. It’s a relatively recent entry in a long, sexist tradition of fantasy literature describing women in specific physical ways, with attributes that correlate to the way they look. To be fair to fantasy literature — more fair than they often are to the women in their pages — not all bad women are unattractive and not all good women are beautiful. But it is the case more often than not. Or to be more accurate, it is rare to find a woman important to the plot whose appearance isn’t a big if not key part of her character. Look at Lord of the Rings, The Chronicles of Narnia, The Once and Future King. I love these books. They are by and large populated by beautiful and unattractive women: women for whom appearance is the focal point. There are few plain or average or even quirky-cute Janes to be found.

Of course, there have always been exceptions: Dr. Susan Calvin in Asimov’s Robot series. Meg in A Wrinkle in Time. The Chubby Girl in Hard-boiled Wonderland (I’d like to note that everyone in the book is described as an archetype, not a name, but also, couldn’t you have called her Attractive Girl or Young Woman or the patriarchal but still less appearance-focused Scientist’s Daughter? I mean, damn). But although there are outliers, the legacy of women’s appearance as paramount quality is a pervasive one. It is getting better, in big and important ways. But beautiful, white, thin, symmetrical, straight, cis women still rule the realms of magic. Within the genre, women’s physical appearance remains a tacitly acceptable bastion of sexism and often racism.

This was a hard pill to swallow because growing up, fantasy was my escape and my delight. It was tough to see that my sanctuary was poisoned. It took me a while to see it. Probably because I’m privileged—my hair looks like spun straw, my skin glows like a plastic bag, and my body shape is somewhere between elf and hobbit—and possibly because like a lot of people who enjoy sword-and-sorcery, I was used to the paradigm of Nerds Against Jocks, Nerds Against Hot Girls, Nerds Against the World. I thought what I loved could never do me wrong, except it did. Like many women, I have a socially acceptable amount of body dysmorphia, which is a fancy way of saying I don’t think I can ever be too pretty or too thin. I don’t actually believe I’m worthless because I’m not the fairest in the land, but there’s a mental undercurrent I don’t know if I’ll ever truly shake. And I don’t solely blame Tolkien for every time I’ve scowled at a mirror, but reading about how “The hair of the Lady was of deep gold… but no sign of age was upon them” is enough to make you reach for the bleach and retinol, trying forever to reach an unattainable Galadriel standard.

Recognizing that fantasy fiction was just as bad as mainstream culture was a cold shower, made icier by the realization that not all fantasy fans agreed. Quite the opposite, in fact: as the Internet grew and nerd culture found many new digital homes, I began to see a smug fan base: people who believed that nerd culture was not only victimized, but a more enlightened tribe than the mainstream masses.

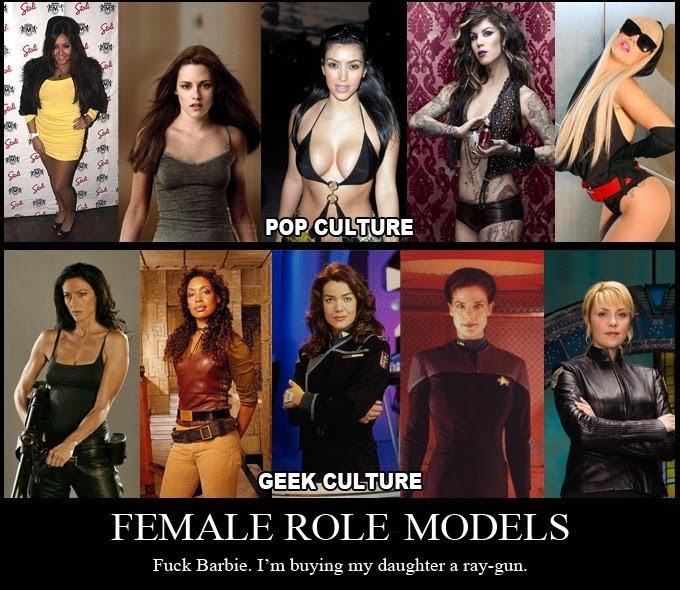

This attitude was captured well in the Female Role Models meme:

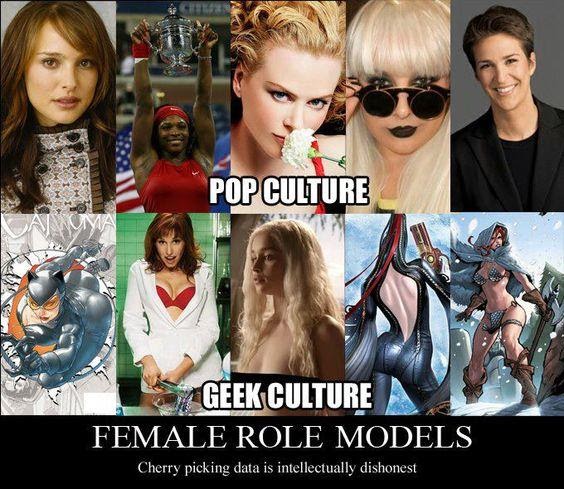

A counter-meme sprung up, pointing out the hypocrisy of the statement:

But the original meme had already circulated, and the thinking behind it was far from over. Treating geek culture as unimpeachable is not only dishonest—it’s dangerous. Look at GamerGate, where game developers Zoë Quinn and Brianna Wu and feminist media critic Anita Sarkeesian received doxing, threats of rape, and death threats, for having opinions about a piece of media. Look at the Fake Geek Girl meme. Look at the backlash to a rebooted Ghostbusters. I don’t even want to talk about Star Wars, but look at Star Wars’ fans reaction to the character of Rose Tico. The list goes on and on, and the message is consistent: women should look and act a certain way, and woe betide anyone who falls out of line.

Is the next step to treat fantasy like the ruined woman from Streams of Silver, forsaking it forever and banishing it to the realms of Things We Don’t Read Anymore? Absolutely not. That’s throwing a magical, beloved baby out with the sexist bathwater. Genre doesn’t exist in a vacuum; it’s forever shifting and hopefully evolving, always informed by the humans that create it. It can be taken back and forward and out and around. And thoughtful female characters in fantasy don’t end with A Wrinkle in Time’s Meg Murry. Take Cimorene from Patricia C. Wrede’s Dealing with Dragons: she’s tall and dark-haired, a departure from her petite, blonde princess sisters, but her most notable attributes are her sense of adventure and independence. She goes on to buddy up with a dragon, Kazul, as well as another princess, Alianora, who is “slender with blue eyes and hair the color of ripe apricots.” Their friendship shows that it’s not about being blonde and slim, dark-haired and tall, or having three horns, green scales with gray edges, and green-gold eyes: it’s that archaic gender norms are limiting and meaningless.

More recently, Valentine DiGriz from Ferrett Steinmetz’s Flex is overweight, attractive, and wryly aware of both. Not long after she’s introduced, she quips, “Is there a word that means ‘pretty’ and ‘dumpy’ at the same time? Hope not. Somebody’d use it to describe me.” This echoes the first reference to her physicality: “She bent over to pick up a large-cupped foam bra, then yanked off her shirt. Paul saw her ample breasts pop out before he averted his eyes.” Though busty and funny, Valentine’s not a funny fat friend trope: she likes to get laid and isn’t shy about it. Beyond all that, she’s an ace videogamemancer who often steps in to save the day.

Sometimes appearance is more key to a character, like in the case of Sunny Nwazue of Nnedi Okorafor’s Akata Witch: “I have West African features, like my mother, but while the rest of my family is dark brown, I’ve got light yellow hair, skin the color of ‘sour milk’ (or so stupid people like to tell me), and hazel eyes that look like God ran out of the right color.” Oh, and Sunny is magical and needs to help capture a serial killer. No big deal.

There are more: Scott Lynch’s The Lies of Locke Lamora. Emma Bull’s War for the Oaks. Noelle Stevenson’s graphic novel Nimona. Anything and everything by Kelly Link or Angela Carter. The point is not that the women in these books are beautiful or unattractive, or even that the way they look isn’t memorable or part of the plot. They have bodies and faces, but a wasp waist or plain face isn’t a beeline to the contents of their souls or significance in the story. Their attributes aren’t code for good or evil, and never all that they are. Physical appearance is one part of a layered, multi-faceted character, because women are human beings, not tired tropes or misogynist fantasies.

Exploring texts where women are treated as fully rounded characters is a great place to start dismantling some of fantasy’s baggage. Reading stuff that’s sexist is good too: it’s important to see it and recognize it for what it is (Peter Pan has interesting ideas and so many problems). Read everything and understand that fantasy is not a pristine chalice in an airless chamber, ready to break at the slightest shift in the atmosphere. It’s raw and powerful and wild, the provenance of old creatures and new gods and spells that can take out continents. Sidelining women through the way they look is definitely the way things often are, but don’t have to be. I can think of few genres better suited to tell stories of a more beautiful world.

Rosamund Lannin reads and writes in Chicago for publications like Lady Churchill’s Rosebud Wristlet, Vol. 1 Brooklyn, and Vice. You can find her on the Internet @rosamund, or anywhere magic and reality hold hands.

Equating beauty with goodness goes all the way back to the Ancient Greeks, who could be very shallow. Of course the rule applied to both sexes, and you don’t see a lot of homley heroes in fantasy either.

The formidable Lady Sybil Vimes, nee Ramkin, from the Discworld novels.

A short story collection from Meisha Merlin – Such A Pretty Face – is (to my admittedly less than knowing view) a nice collection of body positive stories.

Jim C. Hines’ Magic Ex Libris series has a Rubinesque dryad as a major character.

The She-Ra reboot is good at this. There are a lot of “unfit” people onscreen and nobody says a word about it.

Finding any woman, let alone a plumper one, who isn’t a stereotypical virgin, matron, or whore in any guy-centric genre fiction of the last hundred years isn’t that common. In recent years as female literary omnivores have been recognized as a major chunk of book buyers, this has improved. To be honest, though, female viewpoint characters with great bodies in genre fiction are as much wish-fullfillment for women as manly men with abs of steel are for men. I doubt that will change.

Very interesting article.

I’d say beauty standards are arbitrary and subject to change with time, place, culture, and more. We don’t need to conclude that wish-fulfilment in any direction is inevitable, especially when one of the big ideas of body-positivity is to dismantle the idea that conventionally attractive people, however that’s defined, are somehow more valuable or more deserving. Respecting any body that has a human being in it is a good place to start.

I think SFF has a lot of untapped potential when it comes to highlighting this directly. I’m thinking of Joan Abelove’s remarkable YA novel Go and Come Back, which is definitely not SFF but based on intensive anthropological study of Indigenous groups of the Amazon. Our narrator is self-conscious mainly because e.g. her forehead is not flat enough, but she’s confident in how much better-looking she is than the two ugly old women who observe them (i.e. two American anthropologists who are probably white and probably twentysomething graduate students). Any extraterrestrial/supernatural beings who aren’t human but who watch humans judge the heck out of each other, overtly or otherwise, for whatever fine details of appearance probably aren’t going to get it – and that’s as it should be. We shouldn’t get it either, if you see what I mean.

Graphic SFF has the ability to play with this directly – depicting characters’ appearances without needing to comment on them. I’ve been going back and forth for a couple of years now on whether Elsa Kroese and Charlotte E. English’s Spindrift (a gorgeous webcomic) is a subtle sendup of the idea that Pretty Blond Elves are Good and Scrappy Dark Outsiders are Bad. I think so – the writing is certainly sophisticated enough for it. Plus there’s the fact that two of the female leaders of the Pretty Blond Elves (the astute, respected community leader and one of the two gods pulling all the strings in the first place) are definitely not depicted as ridiculously thin. I’m also thinking of Blue Delliquanti when it comes to drawing lots of body types and being refreshingly nonjudgmental about it. Their upcoming graphic novel, I hear, is ‘two non-binary pen-pals go into space together’, and the hints we’ve seen so far suggest that the author is going to be punching through lots of stereotypes, as they’ve been doing in many other ways in Meal (graphic novel, with Soleil Ho, lovely and thought-provoking) and O Human Star (SFF webcomic, self-published, a stunning story).

(Edit: sorry, just caught my own foolish error. I’d unconsciously typed the name of that other semi-famous person named Soleil.)

Beauty is in the eye of the beholder. The beholder viewpoints are limited.

The Flora Segunda books sprang immediately to mind….

Robin Hobb’s Soldier’s Son Trilogy features extremely obese characters in the later two novels who are extensively explored, including sex lives. In this particular world obesity is a result of being associated with a specific type of magic practice. There is a lot more to it than that but anything else is an outright spoiler. Suffice to say Hobb deals multiple characters who would be defined not as chubby or voluptuous but morbidly obese, a fact she makes clear without seeking to demean. In short, fat bodies are normalized here in a way I’ve never seen before.

this trope is why I love Hester from the Mortal Engines books so much (and haven’t seen the movie). One of the truest female anti- heroes I’ve ever read.

Sarah Gailey’s “River of Teeth/A Taste of Marrow” (anthologized with an extra story as “American Hippo” — which refers to actual hippopotami) has a delightful and unapologetically-fat major female character, as well as a non-binary lead.

I need to re-read the “Changewinds” books (I’m pretty sure there’s some content that reads as a bit more problematic now than it did in the 90’s), but one of the main characters is fat and kicks a great deal of ass.

I am 70 yo and all my first reading in SFF was not so much full of only beautiful women, it had mostly no women. I learned to just place myself in the hero spot and read on. It was actually harder when the “babes” started showing up.

Now I’m old and it feels like everything is YA. You just can’t win. Anyway, if you want some strictly short and humorous reads about mid-life women and the magical life take a look at the books of the “Paranormal Women’s Fiction” group. There is a facebook group, A Goodreads list and of course, good old Amazon.

I recently reread the Dealing with Dragons series and it was just as charming as when I read it so many years ago. I love Cimorene’s no nonsense outlook on the all of fantasy tropes, and loved Morwen the witch for bucking traditional “witch” expectations as well. And it never felt performative for any of the characters; they just didn’t like that so they didn’t go along. Way ahead of her time.

I recently reread the original Dragonlance-trilogy, and by the end I was fair choking on the words “slender” and “lithe”. I am fat, and I am a body activist that is VERY passionate about body positivity, body acceptance and fat liberty. I’m so sick of seeing my body vilified in books. How authors gorge themselves on descriptions of bad buys with they “rolls of flesh” and “flabby faces” and “quivering multiple chins”. It’s frustrating that every time my body, fat and disabled that it is, is shown in my favourite literature, it’s as something that is to be ridiculed or disgusted by. Now I’m old enough now not to let it get to me, but especially for teens and young adult that can be so hard. No matter where we turn, be it genre or mainstream fiction, finding positive representation is damn near impossible.

Swordheart by T. Kingfisher. Also Nine Goblins if we count non-human body positivity.

Some of Bujold’s characters in the World of the Five Gods stories.

Akata Witch was very selectively body positive. I understand why it’s important and so many people love it, but there’s casual cracks about weight throughout and fat is regularly used as a stand in for immorality/laziness/downright evil.

Ursula Vernon is pretty good about casual body positivity, and even though it’s not a large element, for me Lady Sybil was one of the first positive fat women I found.

You might be interested in They Don’t Make Plus Size Spacesuits by Ali Thompson; a fantastic collection of short stories that deal with the marginalization of fat people in the future, particularly through technology that ends up control-trolling them.

Mary Brown – “Pigs don’t Fly” series has a non-standard female lead and explore outer beauty perceptions – worth a look

I think Kip Guile in the lightbringer series by Brent Weeks was a good male role model. He was overweight, bullied, insecure, and did amazing things anyway.

Lee Martindale published a chapbook called “The Folly of Assumption” featuring “Stories featuring lead characters that wouldnt blow away in a high wind or give you bone bruises if you hugged them.” IIRC in the introduction, she said it was inspired by hearing the term “fat fantasy novels” and thinking/hoping it referred to fantasy novels about fat people rather than really long books.

The chapbook is out of print. But the stories wereprobably reprintted in in her collection “Bard”’s Road.”

Thank you so much for writing this article, Rosamund. It’s a trend I’d noted in science fiction as well as fantasy, and I’d like to add that as a man, I find it quite stultifying. I want to read about women who are like my friends (or acquaintences, even), and hence do vary quite alot, but rarely do you get that – certainly in the protagonists. Hopefully things are getting better – I do end up reading alot more old stuff than new.

I can think of a few notable exceptions. I always imagined (and I think she’s described this way) Alyx from Joanna’s Russ’s stories as fairly short and not visually striking (apart from her eyes).

I remember I read a Simon Blood fantasy novel when I was a teenager where one of the two protagonists was not thin. I’ve never been able to work out which one.

Oddly, the stand alone book from E.E. “Doc” Smith’s Lensmen series – “The Vortex Blasters” – features a leading female character who is described as curvy and short. She’s a scientist, as I remember. She’s probably one of the most attractive (human) characters in the whole of the series. Surprising that a series which, as much as I love it, plumbs many depths, contains that.

I always imagined the protagonist in Ken Macleod’s stand-alone “Newtons Wake” being kind of squat and broad.

Finally, one of my personal obscure favourites – partially because she bucks so many trend with regards to protagonists in genre fiction – is Jane Palmer. For instance, the main character in “The Planet Dweller” is a single mother of 50 – the opening scene of the novel is her visiting the doctor to talk about the menopause, and being put out by how singularly unhelpful he is.

Why can’t we have more characters like this? We’ve had a glut of the unimaginative ones.

Any of Tamora Pierce’s books. None of her characters are described as fat, but two of her main characters are definitely not skinny. Alanna is short and stocky and Keladry is tall and muscular.

@24: In Tamora Pierce’s Emelan books, Tris is “chubby.”

Discworld’s overall record on body positivity (and all forms of bigotry and representation, really) is patchy. On a number of occasions, the narrative will linger on a character’s fatness as amusing and unattractive — more often regarding men, but sometimes woman. But its vast array of lovable and flawed-but-admirable protagonists might have the highest explicit diversity of protagonist body shape that I’ve encountered in fiction. There are leanly muscular men and sleekly curvy women. There are also big women, downright fat women, fat men, scrawny men, truly flat-chested women, homely faces, and more. The villains also vary, but I think they’re more often conventionally attractive (when they’re not eldritch wossnames of one kind or another). Among the heroes, I’d add a sepecial shoutout to Nanny Ogg. She’s a short, fat, wrinkle-faced, one-toothed old woman…as well as a shamelessly bawdy sensualist and a fearsome, clever opponent.

@25 AeronaGreenjoy – 100% agree about Pratchett. His later books get better about that. Shoutout to Glenda in Unseen Academicals.

In some instances the article is guilty of what it’s trying to condemn. Isn’t complaining that Murakami calls her “chubby girl” instead of “attractive girl” buying into the notion that chubby is bad?

Years ago, I read The Eight by Katherine Neville and fell in love with Lily Rad, the secondary protagonist. She was a chess master who should have been rated higher than she was (sexism). She was described as being larger than life in every dimension – physical, emotional, intelligence. Physically, she was described as being large, with thick legs tapering down to tiny ankles, fond of wearing short dresses – Lily Rad gave absolutely zero f*cks about anyone else’s opinion of her personal style. She cheerfully flew halfway around the world to join in the adventure, seemed to seriously consider a second career as a stunt- or racecar driver (she made some crack about holding the world land speed record among chess masters), was absolutely indefatigable.

Sseanan MacGuire’s wayward children series is a good example as well. There is a fat “mermaid” character and I love her.

On the one hand, I’ve always hated lazy writers who use “fat” to equal “bad” because they can’t be bothered to flesh out their characters realistically (no pun intended). Things have been steadily getting better since I started reading in the sixties.

On the other hand, as a fat woman myself, I have no desire to read about a fat heroine who has to sit down halfway running up a flight of stairs before she can rescue the prince at the top of the tower. My idea of a physical heroine always ran toward the Sigourney Weaver in Aliens type. But more variety would be nice.

I think this it’s important to talk about body positivity in fiction, particularly in spec fic! I also think that body positivity *must* include disabled people and pwd. Using a word like “lame” to mean “uncool”, as a casual insult, instead implies pretty strongly that pwd aren’t really welcome in the conversation and ableism doesn’t matter.

Tattersail – the fat lady with the magic from the Malazan. She was smart, funny, attractive, confident.

@31: Thank you for pointing that out; we’ve updated the article.

If you want a protagonist who keeps going despite being literally lame, check out Jo Walton’s Among Others.

Body negativity doesn’t apply just to women; the long line of obese cowardly men that traces back to Falstaff is the obvious example. (I suspect it goes much further back — Shakespeare was a great re-user of tropes and stories — but I’ve just seen a production of The Merry Wives of Windsor so Falstaff comes to mind.) But sometimes obese men are permitted to be magisterial (mundane example: Nero Wolfe) or at least smarter than any of the pretty assistants or opposition (e.g. Nicholas van Rijn, who also hooks up with the heroine after The Man Who Counts), where AFAICR that wasn’t allowed to women until relatively recently.

Thanks for this…I’m just your generic plain/ugly (depending on who’s looking) woman (maybe even worse in society’s eyes than being ‘fat’ since there’s no ‘but you’d be so attractive if you just…’ for me), and I also at various points in my life have had weight that was closer to chubby than thin (even now, while I understand I’m petite in some ways, know that I’m not exactly willowy) and I remember at times feeling like I was a bit of an alien especially when constantly reading about how importance looks were, how much they were extolled, about lithe, willowy, slender, graceful heroines with beautiful smiles and flowing non-frizzy hair.

I don’t begrudge any of that; heck, in my own writing, I made my own character more attractive than I am because there is a certain social lubricant that goes along with that. But I’ve also in my own life had to unpack my own feelings about ugliness and the value or lack of value in looks so I’m always glad to see more representation of people in books and movies.